With the Zombies Need Brains Kickstarter well underway, and our pledges slowly creeping up on our ambitious funding goal (four anthologies instead of three this year, to mark ZNB’s 10th anniversary!), it is time for my yearly “Writing For a Themed Anthology” post. This post, though, has a bit of a twist, which I’ll share with you at the end of the essay.

This year, I am hoping (Kickstarter gods allowing) to co-edit Artifice and Craft, with my dear friend, Edmund R. Schubert. Edmund is an experienced editor, a fantastic writer, and one of my very favorite people in the world. He and I have been friends for a long, long time, and have worked together on many projects. He edited and contributed to How To Write Magical Words, the book on writing I co-wrote with A.J. Hartley, Faith Hunter, Stuart Jaffe, Misty Massey, and C.E. Murphy. He also edited a couple of my short stories when he was lead editor of the Intergalactic Medicine Show. And I edited a story of his for Temporally Deactivated. We have, however, never co-edited before this. I’m excited.

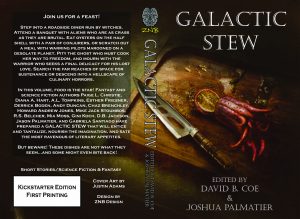

This will be the fifth anthology I have edited for ZNB (after Temporally Deactivated, Galactic Stew, Derelict, and Noir). For each of them, we have had literally hundreds of submissions for about seven open slots. Getting a story into these anthologies is really hard. We editors have the luxury of being highly selective, because we have so many stories from which to choose.

This will be the fifth anthology I have edited for ZNB (after Temporally Deactivated, Galactic Stew, Derelict, and Noir). For each of them, we have had literally hundreds of submissions for about seven open slots. Getting a story into these anthologies is really hard. We editors have the luxury of being highly selective, because we have so many stories from which to choose.

I have found that no matter the theme, there are recurring categories of stories my co-editors and I tend to reject. The first category is fairly obvious, and encompasses the vast majority of rejections: Some stories just don’t work for one of several reasons. The writing might be too rough, the prose unclear and inelegant; the plot might be too hard to follow (or even indecipherable); or the character development might be weak. Put another way, some stories simply aren’t ready for publication. This is fairly self-evident. When reading slush, we expect to encounter a lot of stories that need too much work to be up to standard.

But then there are two other categories that are far more important for our discussion today.

A) Some stories we get are beautifully written and have really fine core ideas. But they fail to move beyond their conceptual strengths and delve into the emotional and narrative potential of those ideas. I can’t tell you how often we read stories like these, and it’s deeply frustrating. Yes, a themed anthology demands stories that have strong conceptual underpinnings. But the idea is only as good as the story it inspires. It’s not enough to show us the great idea. Authors need to develop those ideas, to give them meaning by building compelling characters and creating tension and suspense and all the other emotions that come through in effective storytelling. So if you submit a story, make sure you give us more than an idea. Give us a fully realized story.

B) Some stories we get are brilliantly written AND developed beyond the conceptual to dive into emotion and character arc and all the rest. But they’re not on theme. This year’s theme for our anthology, Artifice and Craft, is pretty simple. The story needs to have at its core some piece of art that has magical or supernatural qualities. It can be any kind of art, from a painting or sculpture, to a theatrical production or musical composition, to a piece of fine furniture or a piece of short fiction. It’s not enough to have the work of art in the story. It needs to be central to the plot, so that if the work of art were taken out, the entire story would collapse. We will make this clear in the call for submissions. And yet, I can guarantee you that we will receive dozens of stories that aren’t at all on theme, or that, for instance, feature a magical artist who creates great art (which is NOT on theme) or that mention a magical novel, but focus on a scheme to steal the book, rather than on the book itself. (Again, that is NOT on theme, because you could replace the book with, say, a diamond, and you’d have the same basic story.)

So make certain you are following the theme as it is described in the guidelines. Make sure you are doing more than just jotting down an idea, that you’re developing that idea with character work and emotion and tension and conflict and all the other good stuff we writers like to do. And then go to town! Because writing for anthologies is really fun.

Finally, allow me to share with you my own story idea. I am editing Artifice and Craft, but I am also an anchor author for Dragonesque, which will be edited by Joshua Palmatier and S.C. Butler. The theme of Dragonesque is dragon stories written from the point of view of the dragon. Fun, right?

So, the dragon in my story is going to a re-enactor, a dragon who does Renaissance Faires and such. Each weekend she allows herself to be “slain” by a knight, and in return she is paid in gold. Except, she’s getting tired of losing all the time, of letting herself be humiliated by these pretend knights. And during the weekend on which my story focuses, she decides to take matters into her own talons, as it were . . . .

Our Kickstarter is going well. We’re about 2/3 of the way to our funding goal. But if I’m going to write my dragon story, and if Edmund and I are going to find the best magical-work-of-art stories available, we first have to fund the anthologies. So if you want to read great short fiction, and/or if you want to have four new anthologies to which to submit your work, please consider supporting the project! Thanks so much!

My editor at Belle Books is a woman named Debra Dixon, and she is a truly remarkable editor. This first book in the Celtic series is our third novel together, after Radiants and Invasives. In our time together, I have never once felt that her responses to my work were intrusive or unhelpful. With each book it’s been clear to me that her every observation, every criticism, every suggestion, is intended to help me tell my story with the greatest impact and in the most concise and effective prose. A writer can’t ask for more. This doesn’t mean I have agreed with every one of her comments. Now and then, I have felt strongly enough about one point or another to push back. And she’s fine with that. That’s how the editor-writer relationship is supposed to work, and she has always been crystal clear: In the end, my book is my book. But even when we have disagreed we have been clear on our shared goal: To make each book as good as it can be.

My editor at Belle Books is a woman named Debra Dixon, and she is a truly remarkable editor. This first book in the Celtic series is our third novel together, after Radiants and Invasives. In our time together, I have never once felt that her responses to my work were intrusive or unhelpful. With each book it’s been clear to me that her every observation, every criticism, every suggestion, is intended to help me tell my story with the greatest impact and in the most concise and effective prose. A writer can’t ask for more. This doesn’t mean I have agreed with every one of her comments. Now and then, I have felt strongly enough about one point or another to push back. And she’s fine with that. That’s how the editor-writer relationship is supposed to work, and she has always been crystal clear: In the end, my book is my book. But even when we have disagreed we have been clear on our shared goal: To make each book as good as it can be. My struggle right now is simply this: Her feedback on this first book is quite extensive and requires that I rethink some fundamental character issues and cut or change significantly several key early scenes. And she’s right about all this stuff. No doubt. This first book has been through several revisions already, and the second half of the book — really the last two-thirds of the book — just sings. I love it. She loves it. The first third is where the problems lie. To be honest, the first hundred (manuscript) pages of this book have always given me the most trouble. I wrote the initial iteration of the book more than a decade ago, and in some ways those early chapters still reflect too much the time in which they were written. They feel dated.

My struggle right now is simply this: Her feedback on this first book is quite extensive and requires that I rethink some fundamental character issues and cut or change significantly several key early scenes. And she’s right about all this stuff. No doubt. This first book has been through several revisions already, and the second half of the book — really the last two-thirds of the book — just sings. I love it. She loves it. The first third is where the problems lie. To be honest, the first hundred (manuscript) pages of this book have always given me the most trouble. I wrote the initial iteration of the book more than a decade ago, and in some ways those early chapters still reflect too much the time in which they were written. They feel dated. Many years back, while I was working on one of the middle books in my Winds of the Forelands quintet, my second series, I came downstairs after a particularly frustrating day of writing and started whining to Nancy about my manuscript. It was terrible, I told her. There was no story there, no way to complete the narrative I’d begun. The book was a disaster, and I might well have to scrap the whole thing.

Many years back, while I was working on one of the middle books in my Winds of the Forelands quintet, my second series, I came downstairs after a particularly frustrating day of writing and started whining to Nancy about my manuscript. It was terrible, I told her. There was no story there, no way to complete the narrative I’d begun. The book was a disaster, and I might well have to scrap the whole thing. After publishing

After publishing  Mostly, as I say, I’ve been editing. My work. Other people’s work. The Noir anthology. I’ve been plenty busy, but I have not been as productive creatively as I would like. And I wonder if this is because of

Mostly, as I say, I’ve been editing. My work. Other people’s work. The Noir anthology. I’ve been plenty busy, but I have not been as productive creatively as I would like. And I wonder if this is because of  But at the very least, we need to see our main heroes grappling with what they have endured and setting their sights on what is next for them. We don’t need this for every character but we need it for the key ones. Ask yourself, “whose book is this?” For me, this is sometimes quite clear. With the Thieftaker books, every story is Ethan’s. And so I let my readers see Ethan settling back into life with Kannice and making a new, fragile peace with Sephira, or something like that. With other projects, though, “Whose book is this?” can be more complicated. In the Islevale books — my time travel/epic fantasy trilogy — I needed to tie off the loose ends of several plot threads: Tobias and Mara, Droë, and a few others. Each had their “Louis” moment at the end of the last book, and also some sense of closure at the ends of the first two volumes.

But at the very least, we need to see our main heroes grappling with what they have endured and setting their sights on what is next for them. We don’t need this for every character but we need it for the key ones. Ask yourself, “whose book is this?” For me, this is sometimes quite clear. With the Thieftaker books, every story is Ethan’s. And so I let my readers see Ethan settling back into life with Kannice and making a new, fragile peace with Sephira, or something like that. With other projects, though, “Whose book is this?” can be more complicated. In the Islevale books — my time travel/epic fantasy trilogy — I needed to tie off the loose ends of several plot threads: Tobias and Mara, Droë, and a few others. Each had their “Louis” moment at the end of the last book, and also some sense of closure at the ends of the first two volumes. Why do I do this? Why am I suggesting you do it, too? Because while we are telling stories, our books are about more than plot, more than action and intrigue and suspense. Our books are about people. Not humans, necessarily, but people certainly. If we do our jobs as writers, our readers will be absorbed by our narratives, but more importantly, they will become attached to our characters. And they will want to see more than just the big moment when those characters prevail (or not). They will want to see a bit of what comes after.

Why do I do this? Why am I suggesting you do it, too? Because while we are telling stories, our books are about more than plot, more than action and intrigue and suspense. Our books are about people. Not humans, necessarily, but people certainly. If we do our jobs as writers, our readers will be absorbed by our narratives, but more importantly, they will become attached to our characters. And they will want to see more than just the big moment when those characters prevail (or not). They will want to see a bit of what comes after. Since writing it, though, I have become sort of fixated on the idea. I am editing my fourth anthology, and already looking at the possibility of editing another. My freelance editing business is attracting a steady stream of clients — I’m booked through the spring and have had inquiries for slots later in the year.

Since writing it, though, I have become sort of fixated on the idea. I am editing my fourth anthology, and already looking at the possibility of editing another. My freelance editing business is attracting a steady stream of clients — I’m booked through the spring and have had inquiries for slots later in the year. I am not an acquiring editor. I do decide, along with my co-editor, whose stories will be in the anthologies I edit, so I suppose in that way I am determining the fate of submissions and, in a sense, “buying” manuscripts. But, for now at least, I don’t make decisions about the fate of novels, and so I don’t have to go toe-to-toe with agents. Good thing. They scare me. (Looking at you, Lucienne Diver.)

I am not an acquiring editor. I do decide, along with my co-editor, whose stories will be in the anthologies I edit, so I suppose in that way I am determining the fate of submissions and, in a sense, “buying” manuscripts. But, for now at least, I don’t make decisions about the fate of novels, and so I don’t have to go toe-to-toe with agents. Good thing. They scare me. (Looking at you, Lucienne Diver.)