As a professional writer — as a professional in the arts — I take on several career roles. I am an artist, of course. I create. I am an editor, and not just in the traditional sense of editing the work of others, as I’m doing now for the Derelict anthology. I also have to edit myself. All the time. Anything I publish will face edits from another editor, but first my work has to get through my own editorial process, which is fairly rigorous.

I am also a business professional. I make career decisions on a weekly-if-not-daily basis, often in consultation with my agent, but not always. Most short fiction projects don’t involve an agent, and the same is true of some projects that I put out through small presses or that I might publish myself.

And, of course, I am responsible for a good deal of my own marketing and publicity. Maintaining this blog, and the websites on which it appears, keeping up with social media, etc. — all of this is time consuming and absolutely essential to my career.

Most of the time, I can fulfill each of these roles without my actions in one coming into conflict with my actions in another. Most of the time. But what about those few occasions when there are conflicts of a sort? What do I do then?

I’m often asked whether my publishers have pressured me to write a book a certain way in order to have more marketing appeal, or (related) whether I have ever had a publisher tell me to write a certain type of book. And the short answer is no. I have worked with many editors on my various series, and (as I mentioned last week) all of them have been very clear in saying that my books are, well, MY books. I retain final creative control over how the books are written. Editors may make suggestions designed to improve the book, but these are suggestions and in the end decisions about content are mine to make.

That said, though, I have throughout my career received suggestions that were designed to maximize the marketability of a book or series. Again, the decision has always been mine to make, but marketing suggestions often come with what we might call “implied incentives.”

“If you do it this way, you may well sell more books and make more money.”

Some of these choices are huge in scope. How huge? Well, when I first pitched the Thieftaker series, I envisioned it as an epic fantasy, set in an alternate world. My editor at the time suggested that turning it into a historical would make it more marketable, and, he added, if I did so Tor would be able to give me a bigger advance. He suggested I set the books in London. I didn’t want to do that, but once I started thinking about it as a historical, I hit on the idea of setting the series in Boston. And, as they say, the rest is history… [Rimshot]

At other times, the artistic/marketing choices are more subtle. And that brings us to the immediate inspiration for this post. I am starting the edits on a supernatural thriller that I have recently sold to a small press. The first book in the series is complete, and I love it. But I have been aware from the very start that the book will not be easy to market. It’s a thriller, intended for adults, but it has a teenaged protagonist and a few elements that convinced my agent we should market the book as a YA thriller. I wasn’t sure about this, but she was, so that was how we pitched it to publishers.

Well, a publisher bought the book, and the series, but like me, the publisher sees the book as an adult thriller and has asked me to make some changes that she feels will make the marketing of the book easier. Her initial suggestions struck me as too drastic, and so we talked and have reached a compromise that satisfies our shared marketing concerns while also preserving my original concept for the book and overall project.

And this is really the point of today’s post.

As an artist, I have in mind a plot, a set of characters, a setting, a tone and pace and voice for the book. I am committed to that initial vision, and certainly will follow it as I write and revise the first iteration. Once we transition from the creative impetus to the actual marketing of the book, though, the business side of my professional brain kicks in a little. I will not jettison my creative vision for money. Not ever. But I also will not — cannot — allow my adherence to a creative vision to undermine a book’s commercial viability. My goal as writer is to put out the best product I can, and to make a living. So, I will strive to find a balance between respecting my creative efforts and working with the publishing professionals who have agreed to put out my book, and who are skilled in the marketing side of the business.

Writing is my art. It’s my profession. It’s my source of income. I’m not interested in preserving my amateur status in order to make the literary Olympics. I want to write, and I want to make money doing it. In order to be satisfied, not only with my work, but also with the results of that work, I need to blend my roles and get the most out of each project — creatively and financially.

That’s what it means to be a professional.

Keep writing.

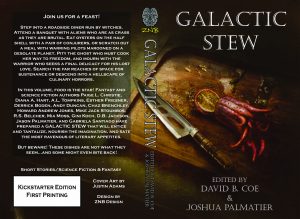

And I’ll start with this: Joshua and I are generous readers. We will read an entire story, even when it’s pretty clear halfway in (or a quarter in…) that the story probably won’t make the cut. Your goal as a writer is to sell us a story, obviously. But really your goal is to make us consider your story on your terms. Here’s what I mean by that: We are expecting to get somewhere between 300 and 400 submissions, for a total of 6 or 7 slots. (Last year, for GALACTIC STEW, we received 409 and selected 7.) Read those sentences again; I’ll wait.

And I’ll start with this: Joshua and I are generous readers. We will read an entire story, even when it’s pretty clear halfway in (or a quarter in…) that the story probably won’t make the cut. Your goal as a writer is to sell us a story, obviously. But really your goal is to make us consider your story on your terms. Here’s what I mean by that: We are expecting to get somewhere between 300 and 400 submissions, for a total of 6 or 7 slots. (Last year, for GALACTIC STEW, we received 409 and selected 7.) Read those sentences again; I’ll wait. But when do I consider the manuscript done? There is some truth to that first answer I gave. I consider all my books works in progress. My very first book, Children of Amarid, published in 1997 and recognized with a Crawford Award two years later, was, to my mind, never really complete. I knew for years that I could make it better. And when we finally got the rights back, I edited the book mercilessly (and did the same to its two sequels) and released the

But when do I consider the manuscript done? There is some truth to that first answer I gave. I consider all my books works in progress. My very first book, Children of Amarid, published in 1997 and recognized with a Crawford Award two years later, was, to my mind, never really complete. I knew for years that I could make it better. And when we finally got the rights back, I edited the book mercilessly (and did the same to its two sequels) and released the