“When I ask ‘What’s Next?’ it means I’m ready to move on to other things. So, what’s next?” — Jed Barlet, THE WEST WING

Yeah, I will seek out almost any excuse to quote from The West Wing, it being my favorite television series of all time. But as it happens, this is a question that’s been on my mind for a while now. In the show, “What’s next?” was more than a change of topic or a jump to the next agenda item. It was also used to turn the page after a setback, to refocus the staff after a triumph, even to look for a new beginning after tragedy.

As is the case with so much that happens in the course of the show’s seven seasons, the quote has long had great significance for me, and this is especially true now.

I know better than to think I can “turn the page” or “move on” from the past year. And even if I could, I’m not certain I would. But I am ready to restart my life, to venture back out into the professional and personal world, to find a new routine that makes room for all the emotional complexity of the new reality my family and I face.

In some ways, I have already started this process. I finished a book a few weeks ago, one I started back in January. It was sort of a work-for-hire, tie-in book, but it was fun to write. The plotting and character work proved absorbing, and because I started it later than I intended, the deadline kept me focused, motivated, and, yes, just a little manic. If it seems like I am avoiding telling you anything specific about the book itself, that’s because I am. Sorry. For now, I can’t really talk about it. When I can, you will all be among the first to know.

I have also written a novella for a new shared-world anthology that will be released this summer by Zombies Need Brains. And, as some of you have seen, I am again accepting clients for my freelance editing business. At the end of this month, I will attend ConCarolinas, my first convention since DragonCon last September. Baby steps. But steps forward, which is the point.

Today, I can also share some news about What’s Next that I think will please a good many of you.

First a little background.

Many of you will have seen my blog post about the trip Nancy and I recently took to Italy. If you haven’t, you should check it out. For the photos, if nothing else. While we were in Venice, I fell in love with the city’s narrow lanes, ancient bridges, and gorgeous architecture. It is, visually speaking, the loveliest city I’ve ever seen. And there are no cars — all travel within the city is by boat, by foot, or by bicycle. Walking the streets was like a journey back in time.

We took tours of the Doge’s Palace and Saint Mark’s Basilica (both were spectacular), and one of our tour guides mentioned that while Venice is a very safe city today, once upon a time it was anything but. And as proof of this, she said, we should pay attention to some of the street names. “Street of the Dead,” “Lane of the Murderers,” “Street of the Head” (that’s not a typo), and more.

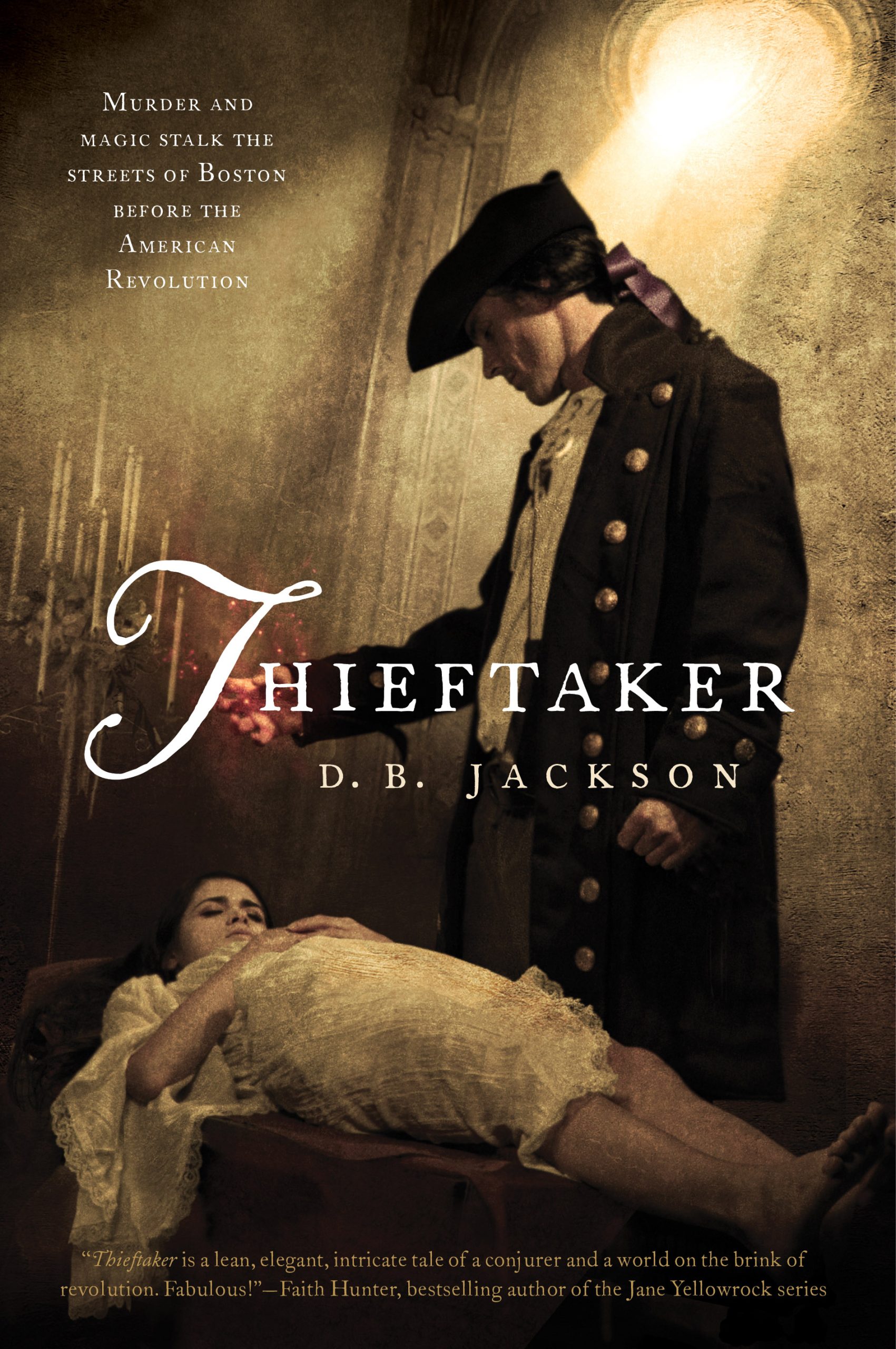

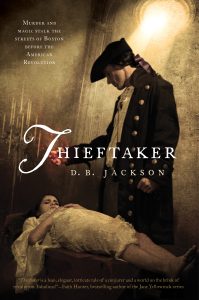

And, of course, this set my writer brain in motion. One thing led to another, and I can tell you now that I am beginning work on a new Thieftaker universe series set in 18th century Venice. I don’t know yet if it will be a spin-off or will feature Ethan throughout. I don’t even know how I am going to get Ethan to Venice, though I have some ideas about that. But I have already commenced my research for the books and I am totally jazzed. One publisher has already expressed interest in seeing a series proposal, so that’s good as well.

What about the rest of my life? What’s next in other realms?

What about the rest of my life? What’s next in other realms?

Well, we’re about to start doing some work on the house — I won’t say it’s overdue, but it comes at a good time. We have more travel planned for later in the year and several weddings to attend this summer and fall. We’ll see Erin. We’ll see other family and many friends. I’ll be at DragonCon late this summer. And we’ll continue to heal, even as we also look for ways to honor Alex’s memory and celebrate her life.

I look forward to crossing paths with many of you in the months to come. We have some catching up to do.

Have a great week.

A week and a half from today, on Friday, August 4,

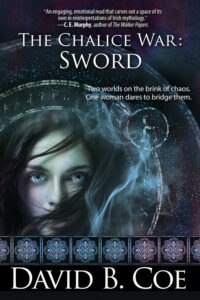

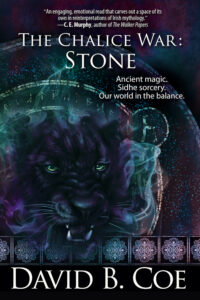

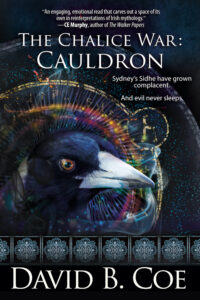

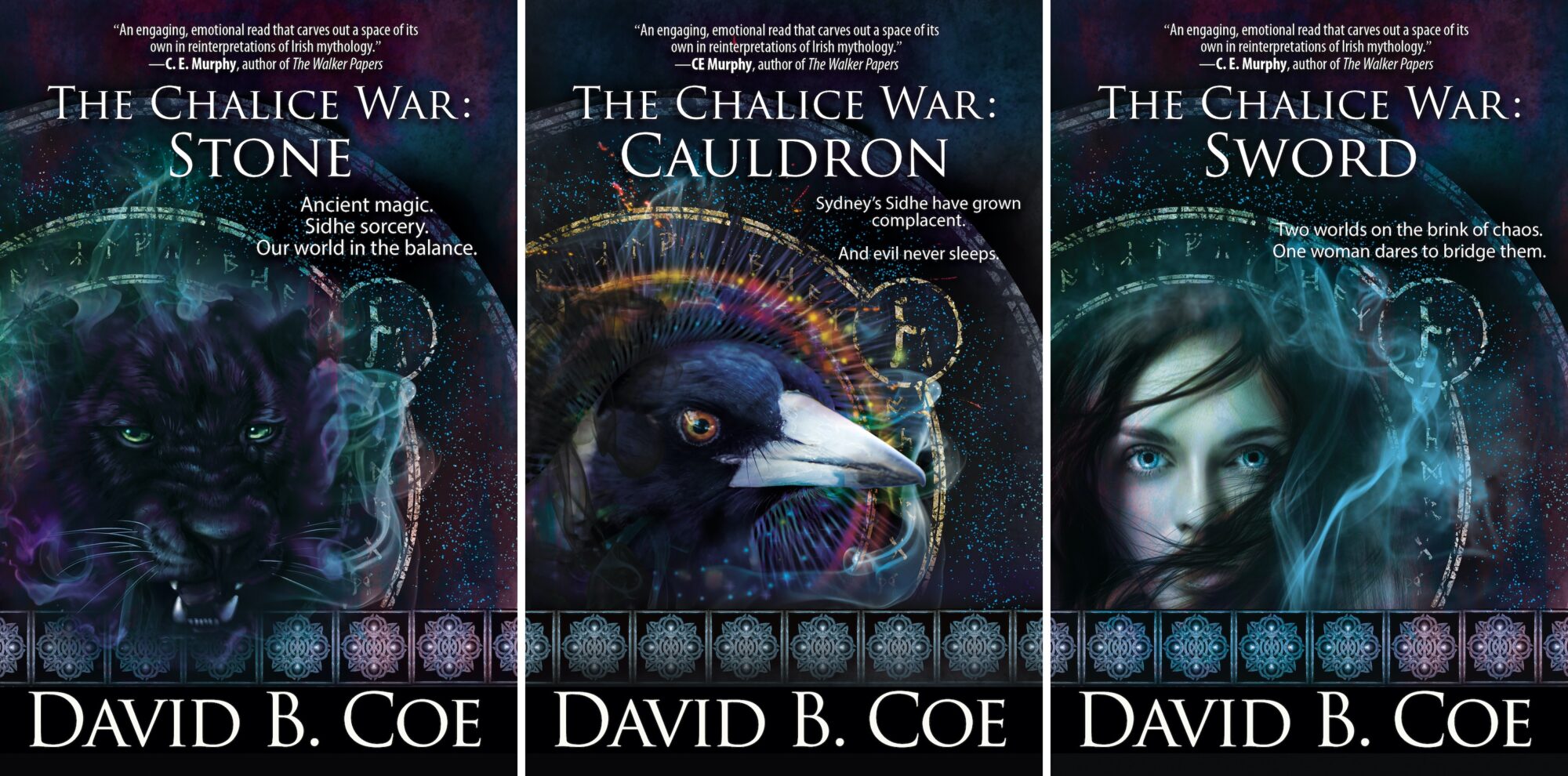

A week and a half from today, on Friday, August 4,  The premise of The Chalice War trilogy is fairly simple. The four treasures of the Sidhe — the Stone of Fal, the Spear of Lugh, the Daghda’s Cauldron, and the Sword of Nuadu — are chalices of magic. As long as they remain in this world, the Above, the Sidhe sorcerers living in our midst can continue to protect our world. But the Fomhoire, masters of the demon Underrealm, seek to take the chalices from our world into the Below, and if they succeed, magic will cease to exist in our world and demons will overrun the face of the earth.

The premise of The Chalice War trilogy is fairly simple. The four treasures of the Sidhe — the Stone of Fal, the Spear of Lugh, the Daghda’s Cauldron, and the Sword of Nuadu — are chalices of magic. As long as they remain in this world, the Above, the Sidhe sorcerers living in our midst can continue to protect our world. But the Fomhoire, masters of the demon Underrealm, seek to take the chalices from our world into the Below, and if they succeed, magic will cease to exist in our world and demons will overrun the face of the earth. You see, I wrote the first iteration of book one, Stone, more than a decade ago, when I was in a lull in my career and was looking for something to write for the fun of it. I loved that first draft, but it needed work, and around the time I finished it, I signed my first Thieftaker contract, putting an end to the aforementioned lull. I started work on the second book, Cauldron, about seven years ago, hit a wall, put it away, came back to it four years later and finished it. Now, usually when I write a series, I know as I begin book one how the last book will end. Not with this series, because when I wrote that first book, I was playing around. I had no idea what it would become. So even after I finished the second book, I still wasn’t sure what to do with the series, because I had no idea how to write the third book without making it simply a repeat of one of the first two.

You see, I wrote the first iteration of book one, Stone, more than a decade ago, when I was in a lull in my career and was looking for something to write for the fun of it. I loved that first draft, but it needed work, and around the time I finished it, I signed my first Thieftaker contract, putting an end to the aforementioned lull. I started work on the second book, Cauldron, about seven years ago, hit a wall, put it away, came back to it four years later and finished it. Now, usually when I write a series, I know as I begin book one how the last book will end. Not with this series, because when I wrote that first book, I was playing around. I had no idea what it would become. So even after I finished the second book, I still wasn’t sure what to do with the series, because I had no idea how to write the third book without making it simply a repeat of one of the first two.

First, though, it occurs to me that in writing about openings last week, I left out one crucial, but easy-to-describe story element: “the inciting event.” The inciting event of your narrative is, quite simply, the thing that jump-starts your story, that takes the characters you have introduced in your opening lines from a place of relative stasis to a place of flux, of change, of tension and conflict and, perhaps, danger. It is the commencement of the narrative path that will carry your characters through the rest of the story. In his description of the Hero’s Journey, Joseph Campbell referred to the inciting event as the “Call to Adventure.” If you’re looking for examples, think of the arrival of the first letter from Hogwarts in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, or the appearance of Gandalf at Bilbo Baggins’s door in The Hobbit. In pretty much all the Thieftaker books and stories, it is the arrival of whoever Ethan’s new client will be for that episode.

First, though, it occurs to me that in writing about openings last week, I left out one crucial, but easy-to-describe story element: “the inciting event.” The inciting event of your narrative is, quite simply, the thing that jump-starts your story, that takes the characters you have introduced in your opening lines from a place of relative stasis to a place of flux, of change, of tension and conflict and, perhaps, danger. It is the commencement of the narrative path that will carry your characters through the rest of the story. In his description of the Hero’s Journey, Joseph Campbell referred to the inciting event as the “Call to Adventure.” If you’re looking for examples, think of the arrival of the first letter from Hogwarts in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, or the appearance of Gandalf at Bilbo Baggins’s door in The Hobbit. In pretty much all the Thieftaker books and stories, it is the arrival of whoever Ethan’s new client will be for that episode. On the other hand, do trust in your story ideas. All of them. Even the old ones that haven’t yet gone anywhere. At some point, you’ll have an idea for a story about three kids living in the subway tunnels beneath New York City. And you won’t have any idea what to do with it. You’ll give up on it. Don’t. It will become Invasives. At another time, you’ll write a story about two women interacting with Celtic deities and trying to protect an ancient, transcendently powerful magical artifact. That one, too, will seem to languish. Trust the story. That book just came out. It’s called The Chalice War: Stone. Believe in your vision.

On the other hand, do trust in your story ideas. All of them. Even the old ones that haven’t yet gone anywhere. At some point, you’ll have an idea for a story about three kids living in the subway tunnels beneath New York City. And you won’t have any idea what to do with it. You’ll give up on it. Don’t. It will become Invasives. At another time, you’ll write a story about two women interacting with Celtic deities and trying to protect an ancient, transcendently powerful magical artifact. That one, too, will seem to languish. Trust the story. That book just came out. It’s called The Chalice War: Stone. Believe in your vision. My “What matters?” series of posts will conclude next Monday, after a Monday Musings post this week that straddled the personal and professional a bit more than usual. In the meantime, I am using today’s Professional Wednesday post to begin pivoting toward the impending release of my new series, a contemporary urban fantasy that delves deeply into Celtic mythology. The series is called The Chalice War, and the first book is The Chalice War: Stone. It will be released within the next month or so, and will be followed soon after by the second book, The Chalice War: Cauldron, and the finale, The Chalice War: Sword.

My “What matters?” series of posts will conclude next Monday, after a Monday Musings post this week that straddled the personal and professional a bit more than usual. In the meantime, I am using today’s Professional Wednesday post to begin pivoting toward the impending release of my new series, a contemporary urban fantasy that delves deeply into Celtic mythology. The series is called The Chalice War, and the first book is The Chalice War: Stone. It will be released within the next month or so, and will be followed soon after by the second book, The Chalice War: Cauldron, and the finale, The Chalice War: Sword. But I never forgot my Celtic urban fantasy, or its heroes Marti and Kel. When I had some spare time, I went back and rewrote the book, incorporating revision notes from friends and from my agent with my own sense of what the book needed. I rewrote it a second time a couple of years later, and having some time, started work on a second volume, this one set in Australia (where my family and I lived in 2005-2006). I stalled out on that book about two-thirds of the way in, but I liked what I had. By then, though, I was deeply involved with the final Thieftaker books and the Fearsson series. And I was starting to have some ideas for what would become the Islevale trilogy.

But I never forgot my Celtic urban fantasy, or its heroes Marti and Kel. When I had some spare time, I went back and rewrote the book, incorporating revision notes from friends and from my agent with my own sense of what the book needed. I rewrote it a second time a couple of years later, and having some time, started work on a second volume, this one set in Australia (where my family and I lived in 2005-2006). I stalled out on that book about two-thirds of the way in, but I liked what I had. By then, though, I was deeply involved with the final Thieftaker books and the Fearsson series. And I was starting to have some ideas for what would become the Islevale trilogy. Around that same time, I was also reading submissions for the Temporally Deactivated anthology, my first co-editing venture. Last year I opened my freelance editing business, and a year ago at this time, I was editing a manuscript for a client.

Around that same time, I was also reading submissions for the Temporally Deactivated anthology, my first co-editing venture. Last year I opened my freelance editing business, and a year ago at this time, I was editing a manuscript for a client. Last week, I wrote about planning out my professional activities for the coming year. This week, I want to discuss a different element of professional planning. My point in starting off with a list of those projects from past years is that just about every year, I try to take on a new challenge, something I’ve never attempted before. I didn’t start off doing this consciously — I didn’t say to myself, “I’m going to start doing something new each year, just to shake things up.” It just sort of happened.

Last week, I wrote about planning out my professional activities for the coming year. This week, I want to discuss a different element of professional planning. My point in starting off with a list of those projects from past years is that just about every year, I try to take on a new challenge, something I’ve never attempted before. I didn’t start off doing this consciously — I didn’t say to myself, “I’m going to start doing something new each year, just to shake things up.” It just sort of happened. As it turns out, these new challenges have brought me to a place where I can say, in all candor, that I have never been happier in my work than I am now. Each time I try something new, I reinvigorate myself as a creator. I force myself out of the tried-and-true, the comfortable. With each of the new projects I mentioned above I had a moment of doubt. I wondered if I was capable of accomplishing what I set out to do. Now, I’m a pretty confident guy when it comes to my writing chops and my ability to help others improve their writing, so those doubts didn’t last long. But they were there each time.

As it turns out, these new challenges have brought me to a place where I can say, in all candor, that I have never been happier in my work than I am now. Each time I try something new, I reinvigorate myself as a creator. I force myself out of the tried-and-true, the comfortable. With each of the new projects I mentioned above I had a moment of doubt. I wondered if I was capable of accomplishing what I set out to do. Now, I’m a pretty confident guy when it comes to my writing chops and my ability to help others improve their writing, so those doubts didn’t last long. But they were there each time. But those new challenges did more than that. They kept my professional routine fresh. I am a creature of habit. I try to write/edit/work every day, so in a general sense, my work days and work weeks don’t change all that much. By varying the content of my job — by writing new kinds of stories and expanding my professional portfolio to include editing as well as writing — I made the routine feel new and shiny and exciting. And at the same time, these new projects made it possible to return to some old favorites, notably the Thieftaker series, with renewed enthusiasm.

But those new challenges did more than that. They kept my professional routine fresh. I am a creature of habit. I try to write/edit/work every day, so in a general sense, my work days and work weeks don’t change all that much. By varying the content of my job — by writing new kinds of stories and expanding my professional portfolio to include editing as well as writing — I made the routine feel new and shiny and exciting. And at the same time, these new projects made it possible to return to some old favorites, notably the Thieftaker series, with renewed enthusiasm. Mostly, as I say, I’ve been editing. My work. Other people’s work. The Noir anthology. I’ve been plenty busy, but I have not been as productive creatively as I would like. And I wonder if this is because of

Mostly, as I say, I’ve been editing. My work. Other people’s work. The Noir anthology. I’ve been plenty busy, but I have not been as productive creatively as I would like. And I wonder if this is because of  Nearly two months ago, early in the new year, I posted on social media that I had some exciting professional news I couldn’t share quite yet. I was thrilled, and wanted to let people know. But I also didn’t want to say anything before all the details had been settled. So I posted my little teaser, forgetting the one immutable rule of the publishing business: Things always happen slower than one thinks they will.

Nearly two months ago, early in the new year, I posted on social media that I had some exciting professional news I couldn’t share quite yet. I was thrilled, and wanted to let people know. But I also didn’t want to say anything before all the details had been settled. So I posted my little teaser, forgetting the one immutable rule of the publishing business: Things always happen slower than one thinks they will. I am not the most talented writer I know. Not by a long shot. I am good. I believe that. My character work is strong. My world building is imaginative. My prose is clean and tight and it flows nicely. I write convincing, effective dialogue and I have a fine eye for detail. My plotting and pacing, which were once just okay, have gotten stronger over the years. I think writing the Thieftaker books — being forced to blend my fictional plots with real historical events — forced me to improve, and that improvement has shown up in the narratives of the Islevale and Radiants books.

I am not the most talented writer I know. Not by a long shot. I am good. I believe that. My character work is strong. My world building is imaginative. My prose is clean and tight and it flows nicely. I write convincing, effective dialogue and I have a fine eye for detail. My plotting and pacing, which were once just okay, have gotten stronger over the years. I think writing the Thieftaker books — being forced to blend my fictional plots with real historical events — forced me to improve, and that improvement has shown up in the narratives of the Islevale and Radiants books.