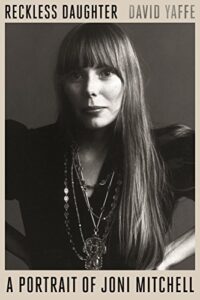

Recently, I have been reading a biography of Joni Mitchell (a holiday gift from my older daughter), a long-time favorite of mine and, in my opinion, the finest songwriter in the history of rock and roll (more on that shortly). It’s been an interesting read — the author is a bit fawning for my taste, and a bit too eager as well to weave Mitchell’s (admittedly phenomenal) lyrics into his prose. But as is often the case when I read biographies of artists I admire, the book made me think about creativity and the artistic process.

Recently, I have been reading a biography of Joni Mitchell (a holiday gift from my older daughter), a long-time favorite of mine and, in my opinion, the finest songwriter in the history of rock and roll (more on that shortly). It’s been an interesting read — the author is a bit fawning for my taste, and a bit too eager as well to weave Mitchell’s (admittedly phenomenal) lyrics into his prose. But as is often the case when I read biographies of artists I admire, the book made me think about creativity and the artistic process.

First, to my statement about Joni Mitchell’s place in rock history: In my opinion, if you look at her lyrical work, her melodies, and the remarkable alternate tunings she brought to her guitar work (a response to the weakening of her hand that resulted from a childhood battle with polio), she emerges as the most innovative, eloquent songwriter rock music has ever seen. And if she was a man, I don’t think there would be any argument. I know Bob Dylan is generally recognized as the best, but though his lyrics are great I believe his music and melodies lack the sparkling originality one sees in Mitchell’s songs. Honestly, I believe Joni’s toughest competition comes not from Dylan but from Paul Simon, whose music is as brilliant as his poetry. And between Simon and Mitchell the comparison is quite close. I prefer Mitchell ever so slightly.

In 1971, as Joni Mitchell was preparing to bring out her next album, she had already established herself as one of THE up-and-coming songwriters on the folkrock scene. Other artists had enjoyed success covering her songs, most notably Judy Collins with “Both Sides Now,” and Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young with “Woodstock.” But Joni herself had yet to become a performing star. That changed with the 1971 release of Blue, an album that is revered, and rightfully so. Its ten songs are uniformly excellent — there isn’t a dud in the collection. And several, most notably the incredible “A Case of You,” are as good as any songs put out by any of the singer-songwriters of the late ’60s and early ’70s. She followed Blue with 1972’s For the Roses, an album that has been added to the Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry, an honor reserved for recordings of historic and/or aesthetic significance. In 1974, she released Court and Spark, her biggest commercial success, and Miles of Aisles, her first live album. She followed these with The Hissing of Summer Lawns (1975) and Hejira (1976). Five years, five studio albums and a live recording. The studio albums are remarkable for their consistent quality (among all the recordings I can think of one song — one — that is less than great) and their stunning musical diversity. The live album is just damn good.

I would challenge anyone to point to a better, more productive five-year stretch from any artist. Yeah, I know: The Beatles. Next to Mitchell’s songs, their early efforts sound simplistic, and the quality of their later production is sporadic.

So, yeah, in my opinion, Joni Mitchell is a once in a generation talent, who was slow to gain the recognition she deserved because she was a woman trying to find fame in a man’s world.

But I also have to say that I found the biography’s personal portrait of her disturbing and disappointing. Her incredible ego, her flirtation with casual racism, her inability to let go of old grudges or admit fault in any number of longstanding feuds, her tendency toward harsh judgments and summary dismissals of colleagues, old lovers, and former business partners, her self-destructive addiction to cigarettes, which ruined her voice — they all combined to leave me with the sense that while I love to listen to her music, I wouldn’t wish to know her. (This is not a quirk of this biography — another Mitchell biography left me feeling much the same way.)

More, I was struck as well by the degree to which her artistic sensibility and creative ambitions undermined her commercial success. I mentioned earlier that the brilliant studio albums she put out in the early 1970s were musically diverse. I cannot emphasize this enough. Blue was the ultimate expression on the singer-songwriter movement. Lyrically, For the Roses is just as good, but the music is far more complex, the instrumentation richer. Court and Spark manages to be commercial, capturing perfectly the pop sensibility of the early 1970s, while also offering breathtakingly eloquent poetry. Hissing of Summer Lawns begins her embrace of jazz themes, taking her music in unexpected directions, and Hejira refines and perfects that combination of jazz and pop.

But with Hejira her audience began to drop off slightly. The following studio album, Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter, which continued her experimentation with jazz and pop themes and pushed her music in less accessible directions, saw a more dramatic drop in sales. The trend continued for the rest of her musically productive years. She never recaptured the success of her early albums. By comparison, Paul Simon continued to experiment musically as well and found renewed success in the 1980s with Graceland and The Rhythm of the Saints. Miles Davis, the king of cool jazz and a favorite of Mitchell’s (and mine), experimented throughout his long career, sometimes with stunning success, other times with results that fell flat with fans and critics alike.

Other musicians I listen to — James Taylor, CSN, Elton John, Bonnie Raitt, to name a few — didn’t change their sounds all that much. They were content to follow the formulas that made them successful without the sort of experimentation and risk-taking one sees in Mitchell’s career arc. As a result, they have continued to sell. Also as a result, their creative journeys seem less impressive, less weighty.

Years and years ago, I met a writing hero of mine, a person I had read early in life whose works made me want to become a published author. This person spoke with some bitterness about the trajectory of their career. They had shifted directions after their early successful series, only to find that their audience fell off dramatically. When they changed directions a second time after the aforementioned project sold poorly, they lost even more of their audience. The writer’s message was clear: If you’re doing well with what you’re writing, keep writing it.

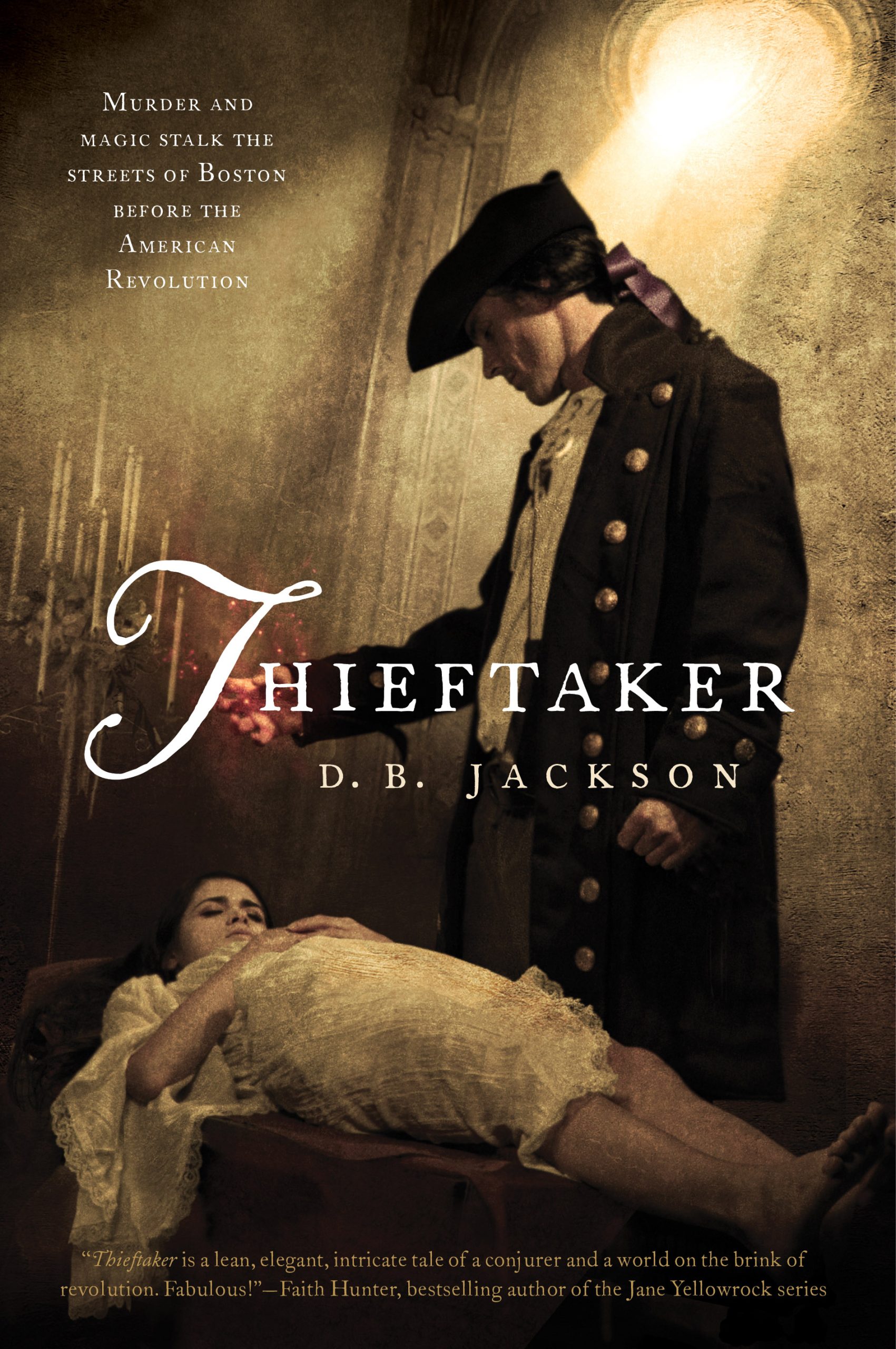

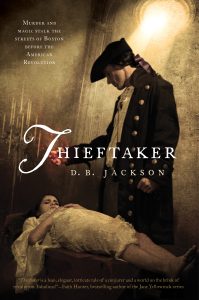

I have changed directions a few times in my career, with mixed commercial results. The Thieftaker books originally represented a marked departure from what I had done before. They sold quite well (albeit under a different name). Other shifts in direction have proven less fortuitous. But every time I have taken on a new project I have been driven more by artistic impulses rather than by commercial ones. I suppose that is evidenced by my sales . . . . [Rimshot] But without daring to put myself on an artistic level with the likes of Joni Mitchell (or any of the other creators I’ve mentioned by name) I would say that I have followed her example, or at least attempted to.

I write the story that burns in my heart. With the exceptions of the media tie-in work I’ve done, I have never taken on a project for financial reasons. I write what I’m eager to write. I love to challenge myself with new sub-genres, with new worlds and characters and themes. I think I would have long since lost interest in writing had I not taken my creativity in so many different directions.

Which is not to say this is the “right” approach, or that others who follow a different course are “wrong.” The fact is, I don’t listen to any of Joni Mitchell’s later albums. I don’t like them. On the other hand, I buy and listen to everything James Taylor puts out, because I know what I’m going to get, and I like the sound. And no, to anticipate the next question, I would not want people to make similar choices with respect to my books.

I have no answers, no absolutes to embrace, no advice to offer. This is one of those Monday posts that’s long on musing and short on solid conclusions. Each of us must follow our own creative path. I admire Joni Mitchell’s integrity, and I am awed by her brilliance. I certainly understand the artistic decisions she has made over the course of her career. And yet, I would have loved for her to put out more albums like those I loved from the Blue-to-Hejira era.

I also know that when people tell me, “I wish you would write more LonTobyn books,” I always want to respond, “Really? Have you seen the stuff I’ve written since? It’s SO much better . . . .”

I have been, and remain, of two minds about all of this. And I continue to muse.

Have a great week.

What about the rest of my life? What’s next in other realms?

What about the rest of my life? What’s next in other realms?

Recently, I have been reading a biography of Joni Mitchell (a holiday gift from my older daughter), a long-time favorite of mine and, in my opinion, the finest songwriter in the history of rock and roll (more on that shortly). It’s been an interesting read — the author is a bit fawning for my taste, and a bit too eager as well to weave Mitchell’s (admittedly phenomenal) lyrics into his prose. But as is often the case when I read biographies of artists I admire, the book made me think about creativity and the artistic process.

Recently, I have been reading a biography of Joni Mitchell (a holiday gift from my older daughter), a long-time favorite of mine and, in my opinion, the finest songwriter in the history of rock and roll (more on that shortly). It’s been an interesting read — the author is a bit fawning for my taste, and a bit too eager as well to weave Mitchell’s (admittedly phenomenal) lyrics into his prose. But as is often the case when I read biographies of artists I admire, the book made me think about creativity and the artistic process.

This will be the fifth anthology I have edited for ZNB (after

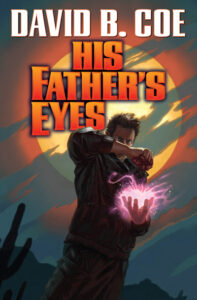

This will be the fifth anthology I have edited for ZNB (after  I would love to be a bestselling author. And with each new project I take on, I wonder if this might finally be the literary vehicle that gets me there. Thieftaker, Fearsson, the time travel books, the Radiants franchise. I had high hopes for all of them. All of them were critical successes. None of them has taken me to that next level commercially. So does that mean I should give up?

I would love to be a bestselling author. And with each new project I take on, I wonder if this might finally be the literary vehicle that gets me there. Thieftaker, Fearsson, the time travel books, the Radiants franchise. I had high hopes for all of them. All of them were critical successes. None of them has taken me to that next level commercially. So does that mean I should give up? The difference between what I did with those two projects and what I am telling you not to do is this: I kept working on these books, but I also moved ahead with other projects, so that I wouldn’t stall my career. Yes, I worked for six years on the first Fearsson book. But in that time, I also wrote the Thieftaker books and the Robin Hood novelization. This, by the way, is also the secret to finding that balance I mentioned. By all means, keep working on the one idea, but do so while simultaneously developing others. Don’t become so obsessed with the one challenge that you lose sight of all else.

The difference between what I did with those two projects and what I am telling you not to do is this: I kept working on these books, but I also moved ahead with other projects, so that I wouldn’t stall my career. Yes, I worked for six years on the first Fearsson book. But in that time, I also wrote the Thieftaker books and the Robin Hood novelization. This, by the way, is also the secret to finding that balance I mentioned. By all means, keep working on the one idea, but do so while simultaneously developing others. Don’t become so obsessed with the one challenge that you lose sight of all else. You won’t get your best ideas sitting at your desk. You’ll get them in the shower. Or, when you’re driving your car, or taking a walk on a snowy day.

You won’t get your best ideas sitting at your desk. You’ll get them in the shower. Or, when you’re driving your car, or taking a walk on a snowy day. It’s happened to all of us. It happened to me writing my new book, Demon Kissed, and the next two in The Summoner’s Mark trilogy, coming from

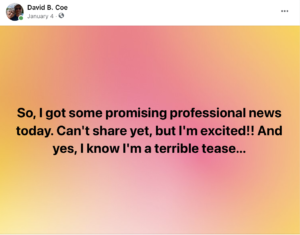

It’s happened to all of us. It happened to me writing my new book, Demon Kissed, and the next two in The Summoner’s Mark trilogy, coming from  Nearly two months ago, early in the new year, I posted on social media that I had some exciting professional news I couldn’t share quite yet. I was thrilled, and wanted to let people know. But I also didn’t want to say anything before all the details had been settled. So I posted my little teaser, forgetting the one immutable rule of the publishing business: Things always happen slower than one thinks they will.

Nearly two months ago, early in the new year, I posted on social media that I had some exciting professional news I couldn’t share quite yet. I was thrilled, and wanted to let people know. But I also didn’t want to say anything before all the details had been settled. So I posted my little teaser, forgetting the one immutable rule of the publishing business: Things always happen slower than one thinks they will. February has begun, Punxsutawney Phil has done his schtick, and time seems to be moving at breakneck speed. In a little over two weeks, Invasives, the second Radiants book, will be released by Belle Books.

February has begun, Punxsutawney Phil has done his schtick, and time seems to be moving at breakneck speed. In a little over two weeks, Invasives, the second Radiants book, will be released by Belle Books. As many of you know, my first series, the LonTobyn Chronicle, had as its narrative core, a magic system in which mages formed psychic, magical bonds with birds of prey: hawks, owls, eagles. To this day, fans of the series mention those relationships between mages and their avian familiars, as the element of the books they enjoyed most.

As many of you know, my first series, the LonTobyn Chronicle, had as its narrative core, a magic system in which mages formed psychic, magical bonds with birds of prey: hawks, owls, eagles. To this day, fans of the series mention those relationships between mages and their avian familiars, as the element of the books they enjoyed most.