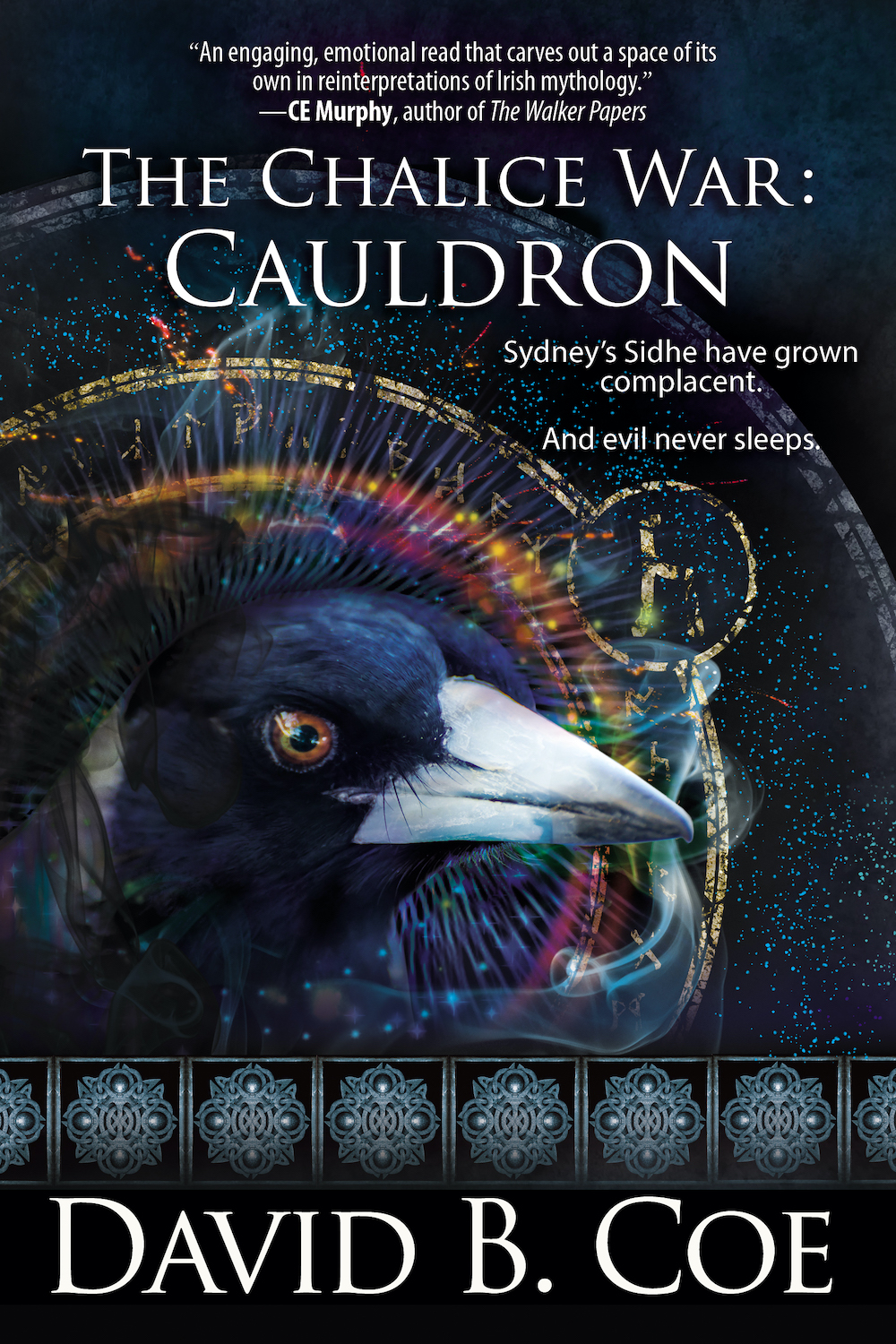

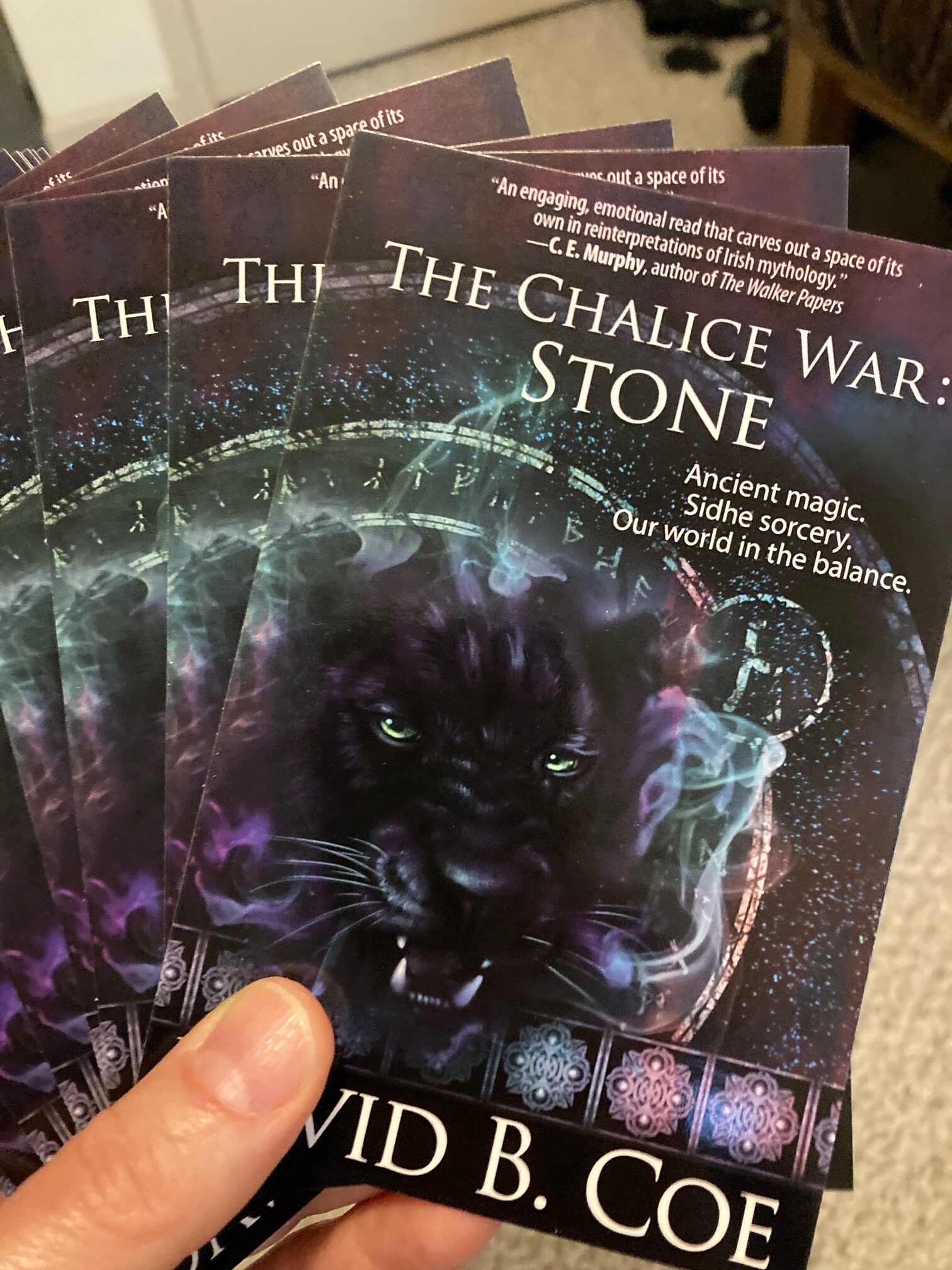

This Friday — the day after tomorrow!! — The Chalice War: Cauldron, the second book in my new Celtic-themed urban fantasy series, will be released by Bell Bridge Books. For those of you thinking, “Wait, didn’t you JUST have a release in this same series?” you’re right, I did. The Chalice War: Stone came out May 5, four weeks before this week’s release. And the final book in the series, The Chalice War: Sword, will be out in July or August. (And wait until you see the jacket art: Spoiler Alert — it’s spectacular!)

This Friday — the day after tomorrow!! — The Chalice War: Cauldron, the second book in my new Celtic-themed urban fantasy series, will be released by Bell Bridge Books. For those of you thinking, “Wait, didn’t you JUST have a release in this same series?” you’re right, I did. The Chalice War: Stone came out May 5, four weeks before this week’s release. And the final book in the series, The Chalice War: Sword, will be out in July or August. (And wait until you see the jacket art: Spoiler Alert — it’s spectacular!)

The thinking behind rapid-fire releases of this sort is pretty simple: If the first book interests readers, and if they fly through that opening volume, they will be eager for more and won’t want to wait. I can’t tell you how many times authors hear from readers, “Oh, I hate waiting for each book in a series to come out, so I wait until the last book is published before I buy any of them.”

This is deeply frustrating for those of us who write and sell books for a living. I get it, of course. Sometimes, fans have to wait a year or more for subsequent volumes in a series to be released. And on occasion, those subsequent volumes never appear at all. The series is dropped by the publisher, or the author simply never gets around to completing the story. Writers aren’t the only ones who can find the publishing schedule frustrating.

Here’s the thing, though: Quite often, the publication of second and third and fourth volumes in a given series is dependent on the sales of the first book. If sales of Book I disappoint, some publishers will decide to drop the series, rather than go to the trouble and expense of putting out the later volumes. And so the reluctance of readers to buy that first book, lest the others don’t find their way to print, becomes self-fulfilling.

The rapid release model is relatively new in the publishing world, but it is intended to prevent this sort of thing from happening. If readers see the second and third books coming out so soon after the first, they will be more willing to buy that initial installment, and might go ahead and just grab all three as they appear. This is certainly my hope.

So, in the spirit of marketing and piquing your interest, let me tell you a bit about Book II, Cauldron. In book I, Stone, we meet Marti Rider, a Sidhe conjurer, and Kelsey Strand, two strangers who are bound to each other by a powerful magical artifact. They are attacked and pursued across the country by Fomhoire demons and their allies, who are intent upon killing them, claiming the artifact as their own, and using it to conquer our world. Along the way, we encounter a host of Celtic immortals who help our heroes or hinder them, depending on their shifting alliances.

In Cauldron, the pursuit of these magical chalices shifts to Australia, where we are introduced to Riann Donovan and her friend (and perhaps more) Carrie Pelsher. Riann is a Sidhe sorcerer who has fled the States to Australia to escape a tragic past. Carrie is a journalist with a strange affinity for magic. When the Sidhe community in Sydney is devastated by a coordinated Fomhoire assault, the two women find themselves in a race against time and a dance of intrigue among gods, Furies, and demons. And yes, for those wondering, Marti and Kel will find their way to Australia to join the fun.

As I’ve said before, I love all of these books. Writing Cauldron allowed me to draw upon experiences and memories from the year I spent Down Under. Many of the locations described in the book are places Nancy, the girls, and I visited. It was a special book to write. And I hope you enjoy it.

And, to whet your appetite for the book even more, here is a short excerpt! Enjoy!

*****

The train had just pulled out of Redfern station when the first frisson of magic brushed across Sara’s skin. She shivered, tasting darkness in its touch.

Fomhoire. Here, in the middle of Sydney. Nearby and closing in, accompanied by . . . by what? Wight? Demon? Yes, demon. All this she read in that initial contact. More, she sensed the Fomhoire had already found her, was intent on her and closing the distance between them.

Sara stood, crossed to the nearest of the sliding doors, and stared out into the inky black of the railway tunnel, desperate for the light of the next station. Never had the distance between Redfern and Central felt so great. The train car rocked, and she grabbed hold of the steel pole beside her to keep from tumbling into the lap of a young businessman.

“Pardon me,” she whispered.

His gaze flicked to her. He answered with a nearly imperceptible nod and turned his attention back to the Herald.

Morning commuters crowded the CityRail trains and stations. Surely Fomhoire assassins wouldn’t attack her here, in front of so many.

A small voice in her mind replied, Why not?

She wore work clothes, carried her briefcase, was on her way to her office in the CBD. Roger, her tabby, her conduit, was at home, safe in her flat, too far away to help her with spells. She was powerless, defenseless.

The train slowed—finally!—and the train guard announced their arrival at Central Station.

“Change here for Northern, Carlingford, North Shore, Cumberland. . . .”

The moment the doors opened, she pushed her way out, heedless of the men and women in front of her and those on the platform waiting to board. People shouted after her; a few muttered obscenities. She didn’t care. She hurried to the nearest stairway, one that would take her to the concourse. The magic followed, aimed like a weapon at her back.

By the time Sara reached the top of the stairs, she was breathing hard, sweating through the blouse she wore beneath her blazer. She switched her briefcase to the other hand, wiped her slick palm on her skirt.

She kept to the crowd, surrounding herself with people, using them as shields and searching frantically for anyone who might give off enough glow to let her defend herself.

How can there be Fomhoire in Sydney?

She and the others maintained a network, a web of magic. Like Sidhe in other parts of the world, they watched for portals and Fomhoire incursions from the Underrealm. As far as she knew, they had sensed nothing.

For decades, Sara and her fellow Sidhe had protected one another, warned one another. These last several years had been quiet, peaceful. She knew other Sidhe in countries far from Australia had battled Fomhoire recently. Harrowing reports had reached her from the States, from Europe and Africa and Asia. But here . . . . Relative peace had reigned for so long, she had grown comfortable, lax. Caution needed to be a routine, like exercise. And she had grown lazy. How many mornings had she left her flat without taking the simple precaution of warding herself? This morning had been no different from yesterday, from the day before, from the one before that. Except it was entirely different. And she might well die because of it.

She exited the gates, threaded her way through the throng in the concourse, hoping to lose her pursuers among the masses. She would exit the station onto Pitt Street and grab a taxi. That was her plan anyway.

As she neared the doors at the west end of the concourse, she sensed more magic. Wights probably, but without Roger, she wouldn’t stand much chance against them, either. She slowed, halted. People flowed around her on either side, as if she were a stone in a stream.

Eddy Street then—the nearest exit.

After a single step in that direction she stopped again. More magic. They had her surrounded.

Another train perhaps. If she could return to the gates and get to a North Shore platform, or maybe the Illawarra line . . . .

A spell electrified the air and made the hairs on her neck stand on end. Sara could do nothing except brace herself for its impact.

Magic fell upon her an instant later, obliterating thought, will, consciousness. She couldn’t say if she remained standing or fell to the floor or ran in circles like some ridiculous child’s toy. Time was lost to her.

When next she became aware of her surroundings, she was still upright in the middle of Central Railway Station’s Grand Concourse. A woman stood before her radiating so much power Sara had to resist an urge to shield her eyes.

“Hello, Sara,” she said in a cool alto and an accent that would have convinced any native Aussie.

“Who are you?” Sara asked, surprised she could speak.

The woman smiled. She was beautiful, of course. The Fomhoire always were here in the Above, regardless of how they appeared in the demon realm. Pale blue eyes, flawless olive skin, golden brown hair that fell in a shimmering curtain to her shoulders. As brilliant and superficial as a Carnival mask. She wore jeans and a long sleeve Sydney FC T-shirt; nothing that would have made her stand out in a crowd.

A second form hovered at her shoulder, as hideous as the woman was lovely, as ethereal as she was solid. It appeared to be little more than a cloud; shapeless, smoke grey, undulating. What might have been eyes shone dully from within the shadow, like stars partially obscured by a nighttime haze. Its lone substantial feature was a mouth at its very center, nearly round and armed with several rows of spiny teeth.

Two demons. One ghastly, the other lovely. Both deadly, no doubt.

None of the people passing by took note of them. Sara sensed that she, the Fomhoire, and the cloud demon were invisible to all.

I applied for the workshop back in March, and was fortunate to be accepted along with a group of eight other writers, all of them intelligent, inquisitive, totally engaged, and eager to learn. It was an amazing week, filled with fascinating lectures, wide-ranging discussions, and very cool demonstrations. We learned a ton, laughed even more, and benefitted from the awesome knowledge and enthusiasm of our three teachers. The weather in Wyoming was a bit uncooperative, denying us the opportunity to spend an evening looking through telescopes, but otherwise the week was all we could have hoped for.

I applied for the workshop back in March, and was fortunate to be accepted along with a group of eight other writers, all of them intelligent, inquisitive, totally engaged, and eager to learn. It was an amazing week, filled with fascinating lectures, wide-ranging discussions, and very cool demonstrations. We learned a ton, laughed even more, and benefitted from the awesome knowledge and enthusiasm of our three teachers. The weather in Wyoming was a bit uncooperative, denying us the opportunity to spend an evening looking through telescopes, but otherwise the week was all we could have hoped for.

All those great ideas you have for jacket art? They’re not as great as you think they are. Seriously. We are a writer. And we’re very, very good at that. We are NOT a graphic artist. We are NOT a marketing expert. I remember when the first Thieftaker novel went into production, I had what I thought was SUCH a wonderful idea for the jacket art. A can’t miss idea. PERFECT for the book. It wasn’t any of those things. The moment I saw Chris McGrath’s image for the book, which WAS brilliant and wonderful and perfect, I understood that no one should ever put me — us — in charge of selecting jacket art.

All those great ideas you have for jacket art? They’re not as great as you think they are. Seriously. We are a writer. And we’re very, very good at that. We are NOT a graphic artist. We are NOT a marketing expert. I remember when the first Thieftaker novel went into production, I had what I thought was SUCH a wonderful idea for the jacket art. A can’t miss idea. PERFECT for the book. It wasn’t any of those things. The moment I saw Chris McGrath’s image for the book, which WAS brilliant and wonderful and perfect, I understood that no one should ever put me — us — in charge of selecting jacket art. On the other hand, do trust in your story ideas. All of them. Even the old ones that haven’t yet gone anywhere. At some point, you’ll have an idea for a story about three kids living in the subway tunnels beneath New York City. And you won’t have any idea what to do with it. You’ll give up on it. Don’t. It will become Invasives. At another time, you’ll write a story about two women interacting with Celtic deities and trying to protect an ancient, transcendently powerful magical artifact. That one, too, will seem to languish. Trust the story. That book just came out. It’s called The Chalice War: Stone. Believe in your vision.

On the other hand, do trust in your story ideas. All of them. Even the old ones that haven’t yet gone anywhere. At some point, you’ll have an idea for a story about three kids living in the subway tunnels beneath New York City. And you won’t have any idea what to do with it. You’ll give up on it. Don’t. It will become Invasives. At another time, you’ll write a story about two women interacting with Celtic deities and trying to protect an ancient, transcendently powerful magical artifact. That one, too, will seem to languish. Trust the story. That book just came out. It’s called The Chalice War: Stone. Believe in your vision. I continue to read through and revise the books of my Winds of the Forelands epic fantasy series, a five-book project first published by Tor Books in 2002-2007. The series has been out of print for some time now, and my goal is to edit all five volumes for concision and clarity, and then to re-release the series, either through a small press or by publishing them myself. I don’t yet have a target date for their re-release.

I continue to read through and revise the books of my Winds of the Forelands epic fantasy series, a five-book project first published by Tor Books in 2002-2007. The series has been out of print for some time now, and my goal is to edit all five volumes for concision and clarity, and then to re-release the series, either through a small press or by publishing them myself. I don’t yet have a target date for their re-release. We are often our own most unrelenting critics. This is certainly true for me in other elements of my life. I am hard on myself. Too hard. And, on a professional level, I am the first to notice and criticize flaws in my writing. So reading through old books in preparation for re-release is often an exercise in self-flagellation. It was with the LonTobyn reissues that I did through Lore Seekers Press back in 2016. And it is again with the Winds of the Forelands books.

We are often our own most unrelenting critics. This is certainly true for me in other elements of my life. I am hard on myself. Too hard. And, on a professional level, I am the first to notice and criticize flaws in my writing. So reading through old books in preparation for re-release is often an exercise in self-flagellation. It was with the LonTobyn reissues that I did through Lore Seekers Press back in 2016. And it is again with the Winds of the Forelands books. As I have read through this first book in the story, polishing and trimming the prose, I have rediscovered that narrative. I remember far less of it than I would have thought possible. Or rather, I recall scenes as I run across them, but I have not been able to anticipate the storyline as I expected I would. There are so many twists and turns, I simply couldn’t keep all of them in my head so many years (and books) later.

As I have read through this first book in the story, polishing and trimming the prose, I have rediscovered that narrative. I remember far less of it than I would have thought possible. Or rather, I recall scenes as I run across them, but I have not been able to anticipate the storyline as I expected I would. There are so many twists and turns, I simply couldn’t keep all of them in my head so many years (and books) later. I gots swag!!!

I gots swag!!! As I say, “trust your reader” is essentially the same as “trust yourself.” And editors use it to point out all those places where we writers tell our readers stuff that they really don’t have to be told. Writers spend a lot of time setting stuff up — arranging our plot points just so in order to steer our narratives to that grand climax we have planned; building character backgrounds and arcs of character development that carry our heroes from who they are when the story begins to who we want them to be when the story ends; building histories and magic systems and other intricacies into our world so that all the storylines and character arcs fit with the setting we have crafted with such care.

As I say, “trust your reader” is essentially the same as “trust yourself.” And editors use it to point out all those places where we writers tell our readers stuff that they really don’t have to be told. Writers spend a lot of time setting stuff up — arranging our plot points just so in order to steer our narratives to that grand climax we have planned; building character backgrounds and arcs of character development that carry our heroes from who they are when the story begins to who we want them to be when the story ends; building histories and magic systems and other intricacies into our world so that all the storylines and character arcs fit with the setting we have crafted with such care. And because we work so hard on all this stuff (and other narrative elements I haven’t even mentioned) we want to be absolutely certain that our readers get it all. We don’t want them to miss a thing, because then all our Great Work will be for naught. Because maybe, just maybe, if they don’t get it all, then our Wonderful Plot might not come across as quite so wonderful, and our Deep Characters might not come across as quite so deep, and our Spectacular Worlds might not feel quite so spectacular.

And because we work so hard on all this stuff (and other narrative elements I haven’t even mentioned) we want to be absolutely certain that our readers get it all. We don’t want them to miss a thing, because then all our Great Work will be for naught. Because maybe, just maybe, if they don’t get it all, then our Wonderful Plot might not come across as quite so wonderful, and our Deep Characters might not come across as quite so deep, and our Spectacular Worlds might not feel quite so spectacular. Okay, yes, I’m making light, poking fun at myself and my fellow writers. But fears such as these really do lie at the heart of most “trust your reader” moments. And so we fill our stories with unnecessary explanations, with redundancies that are intended to remind, but that wind up serving no purpose, with statements of the obvious and the already-known that serve only to clutter our prose and our storytelling.

Okay, yes, I’m making light, poking fun at myself and my fellow writers. But fears such as these really do lie at the heart of most “trust your reader” moments. And so we fill our stories with unnecessary explanations, with redundancies that are intended to remind, but that wind up serving no purpose, with statements of the obvious and the already-known that serve only to clutter our prose and our storytelling. I should have enjoyed last week. We had the release of The Chalice War: Stone, the first book in my new Celtic-themed urban fantasy. Lots of spring migrants (talking ’bout birds here) moved through our area of the Cumberland Plateau, so I had plenty of good bird sightings. The weather was cool and clear (mostly), and my morning walks were crisp and golden. As I say, it had all the makings of a fine week.

I should have enjoyed last week. We had the release of The Chalice War: Stone, the first book in my new Celtic-themed urban fantasy. Lots of spring migrants (talking ’bout birds here) moved through our area of the Cumberland Plateau, so I had plenty of good bird sightings. The weather was cool and clear (mostly), and my morning walks were crisp and golden. As I say, it had all the makings of a fine week. Another teaser, to get you excited for tomorrow’s release from

Another teaser, to get you excited for tomorrow’s release from