So many professional issues on my mind today — I’m finding it hard to organize my thoughts into something coherent.

So many professional issues on my mind today — I’m finding it hard to organize my thoughts into something coherent.

These remain hard times for creators. Writers, musicians and composers, visual artists of all sorts, actors and directors, dancers and choreographers. I could go on, but you get the point. The irony of art: it is considered a solitary endeavor, when in fact it is anything but. We all know the clichés of the lonely artist working in isolation, the writer holed up with her computer, tapping away at the keyboard, churning out her next story.

The truth is, though, art is decidedly communal. The act of creation is only the beginning. All art is interactive. Music must be heard. Paintings and photographs must be seen. Stories must be read. Because every song and book and painting has as many lives as there are people who experience it. Twenty people might read my book — or better yet, twenty thousand people might read it — and each would experience it their own way. Same with songs. Same with works of art. Creation is incomplete until it is received.

And so when a pandemic prevents that interaction between creation and audience, art suffers. So does the artist. I can write as many books in isolation as time allows. But until I know my book is being read by someone, I don’t feel that I’ve accomplished anything.

A dear friend posted a couple of times last week about writing in the COVID age. His first post touched on the slowness of the industry right now. Again, we writers can turn out new books, but if the publishing industry does nothing with them, we struggle to reach our readers. And right now, the publishing industry is the literary equivalent of a clogged sink. Nothing is flowing. So it wasn’t that surprising when, a couple of days later, this same friend shared an article about how hard it is to be productive right now. The dialectic between writer and reader is about far more than books sales. It is, as I indicated above, the way we complete the creative experience. When we know that our books are going nowhere, that they have no immediate hope of reaching audience, our motivation leaches away. And without motivation, we’re lost.

A couple of weekends ago, at Boskone, I moderated a panel on self-defining success. This is an important topic for me; I believe we must take satisfaction in our work on our terms. There is a difference, though, between, on the one hand, finding internal affirmation for our work and our careers, and, on the other, working in a vacuum.

So, where am I going with this?

I guess here: I will continue to write with an eye toward big-press publishing. I have not given up on “New York” entirely. But I am currently writing and editing for small presses. Working through an imprint I have developed with a couple of friends, I am bringing out my own work.

I am, in effect, declaring my independence. I am writing for myself, and for the audience I can reach. And I am worrying far less about what the imprint on the spines of my books says about my status as a writer.

A confession: A couple of years ago, after a disappointing stretch, a series of serious professional setbacks, and a particularly demoralizing experience at a convention, I was ready to quit. I’d had enough. I had been kicked, and kicked again, and kicked a third time. My ego had been brutalized. I didn’t want to write. I certainly didn’t want to deal with any more reversals like those I’d just experienced. I was done.

Except, obviously I wasn’t. I still had stories to tell. I still had characters in my head and heart who clamored for attention. I still had things to say. And while I thought I didn’t want to write anymore, I was wrong. Turns out, I can’t go more than a week or two without writing something. I get grumpy. I snarl and mope and brood and rant. Very, very unattractive. Nancy never says anything when I get this way. Not directly. But she’ll ask me, “So what are you working on today?” And the subtext of that question is, “When are you going to start behaving like an adult human again?”

It has taken me a while to reach the place I’m in now. It was a process, as fraught and difficult as the creation itself can be. But I’m here now. I have an idea of what success looks like, and it has far, far more to do with contentment and peace of mind than it used to. I have a sense of what my career will look like going forward, and while some of my old ambition remains, I am happy — eager even — to approach publication and editing and other professional pursuits in a way that preserves my emotional health and feeds the joy I derive from the simple act of telling stories.

Don’t worry. I have no intention of quitting. I have stories to tell, short form and long, and I have every intention of putting them in the hands of readers.

Because creation is communal. It is a never-ending conversation. And we’re all part of it.

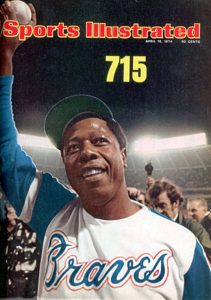

I was watching that night, along with pretty much every other eleven year-old, baseball-loving boy in America. I remember everything about it — the call from announcer Vin Scully, the twist and high stare of Dodgers pitcher Al Downing as he watched the ball sail out over left field, Aaron’s joyful trot around the bases, the two white guys in civilian clothes who appeared out of nowhere as he rounded second base and patted his back and shoulder, the way his jubilant teammates mobbed him at home plate and put him on their shoulders. I still have the issue of Sports Illustrated from the next week, with Aaron on the cover holding up the baseball next to a golden, bolded “715.” And I also still have the special edition baseball card Topps issued that same year proclaiming Aaron baseball’s home run king.

I was watching that night, along with pretty much every other eleven year-old, baseball-loving boy in America. I remember everything about it — the call from announcer Vin Scully, the twist and high stare of Dodgers pitcher Al Downing as he watched the ball sail out over left field, Aaron’s joyful trot around the bases, the two white guys in civilian clothes who appeared out of nowhere as he rounded second base and patted his back and shoulder, the way his jubilant teammates mobbed him at home plate and put him on their shoulders. I still have the issue of Sports Illustrated from the next week, with Aaron on the cover holding up the baseball next to a golden, bolded “715.” And I also still have the special edition baseball card Topps issued that same year proclaiming Aaron baseball’s home run king.