Dear Younger Me,

Yes, that’s really our hairline now. Calm down. It’s not— Would you please calm down? Thank you. What did you expect? Seriously. Dad was bald. Bill and Jim had lost their hair by the time they were thirty. You thought we’d make it through middle age with hair like George Clooney’s? We didn’t make it through middle age with ANYTHING like George Clooney’s. On the bright side, our beard finally filled in, so there’s that . . . .

But this isn’t about how we look, thank goodness. This is a letter to you, my younger self, about other things I wish I had known when I was your age (whatever age that might be exactly). So read on, Younger Me, and if you happen to run across a time machine at some point, remember this stuff, okay?

Let’s start with this, because really nothing is more important: You know how you feel most of the time that you’ll always be alone, that you’ll never meet the right person? Well, I can assure you, you won’t be and you will. She is brilliant, caring, funny. She shares many of your interests and, more important, she shares your values. She is strong and insightful, charming and generous. And . . . What’s that? Yes, she actually loves you. I know: I couldn’t believe it either.

What?

[Sigh]

Yes, Younger Me, she’s also hot.

And together, we have two brilliant, strong, funny, beautiful daughters. You will be blown away.

More good news — and we can discuss this more on Wednesday: You will have that writing career you’ve been dreaming of since you were six. There will be a few detours along the way, some bumps and bruises. It won’t be exactly the career we imagined; it might not reach the heights to which we’ve aspired. But it’s our career. We made it, we sustained it (with the support and encouragement and love of the aforementioned life partner and children), we earned it. We should be proud of it.

Don’t know if you can do much about his one, but I should mention it — if, around 1993 or so you have a chance to get the rookie card of a Yankee prospect named Derek Jeter, go ahead and pick one up. Or ten. Or fifty. Slide it (them) into a nice plastic sleeve for protection and put it (them) away. Trust me, you’ll be glad you did.

You know those episodes we go through, and have since we were little — nausea, shaking hands, extreme ill-defined terror? Those aren’t normal. I know Dad used to tell us he experienced them, too, and he might well have been telling the truth. But that doesn’t mean they were routine or natural. He meant to reassure. He loved us and wanted to help. But by normalizing them, he kept us from doing something about them at a younger age. Along the same lines, you know how for so very long we brushed off our tendency toward unexplained worry and stress, saying that we were “high strung,” or some such? Turns out, that’s not high strung.

We have Generalized Anxiety Disorder, and we have Panic Disorder. And we didn’t need to suffer with either for nearly so long. Do something about them. Soon. Please. For our well being. Friends have encouraged us to try therapy. I finally did when we were 58. I wish we’d done it forty years sooner.

For your sake and mine, please work harder at the guitar. Yes, we still play. Yes, I’m better than you are, which is as it should be. But with work and practice, with less laziness and self-satisfaction, we could have been so good. I can’t have expected us to work at guitar the way we did at writing — one was a hobby, the other a profession — but a bit more work would have brought us such joy.

Never ever ever take your car to Toyota of Palo Alto. Just don’t.

Look at your book shelf, the one with all the fantasy novels on it. You’re going to wind up meeting nearly every author represented there. Many of them will become good friends. Yes, including Guy Gavriel Kay. Pretty cool, right?

Spend as much time as you can with Mom and Dad. Be as tolerant as you can be of Bill’s flaws and idiosyncrasies. Love them. Cherish them. We won’t have nearly as much time with them as we deserve, and we will miss them every day for the rest of our lives. I know, Mom and Dad can be annoying now and then, and occasionally Bill infuriates us. They’re family, and sometimes family is like that. But the hole their absence leaves in our life dwarfs these temporary frustrations. Extend to them the grace and forgiveness you would want from all those we love.

Those amazing friends we made at Brown, the ones who enriched our life there and made it the most memorable time of our early life? Yeah, they’re still our dear friends, still enriching our life. Treasure them.

The rest is pretty much common sense. Dial back the weed — we will later anyway; might as well preserve a memory or two. Don’t drink too much — you don’t hold your booze as well as you think you do. Exercise. Eat right. Take care of yourself. Life is precious, and we don’t want to miss a thing. Read more. Yes, we read a good deal. Read more. Trust me. No one ever looked back from the vantage point of their dotage and thought, “I wish I’d put all those books aside and watched more TV.” Be good to the people we love. Slow down and savor all those things we enjoy doing. Let go of grudges and jealousy and regrets. They do us no good.

Oh, and along the lines of that Derek Jeter thing — those people at Apple who early on made all those weird-looking, quirky computers? Turns out they were on to something. If you get a chance, buy a few shares . . . .

Best wishes,

Older David

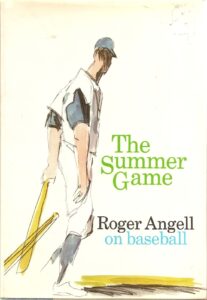

Beginning in 1962, and continuing through most of the next sixty years, Angell wrote about baseball, contributing articles to The New Yorker a couple of times each season, usually once during spring training, and once at the end of the World Series. Some seasons he added a mid-season essay. His articles were later collected in volumes — The Summer Game (1972), Five Seasons (1977), Late Innings (1982), Season Ticket (1988), and Once More Around the Park (1991). I own all of them, and have read them multiple times.

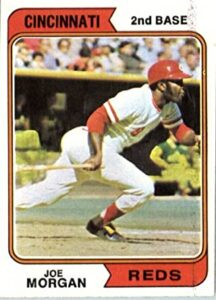

Beginning in 1962, and continuing through most of the next sixty years, Angell wrote about baseball, contributing articles to The New Yorker a couple of times each season, usually once during spring training, and once at the end of the World Series. Some seasons he added a mid-season essay. His articles were later collected in volumes — The Summer Game (1972), Five Seasons (1977), Late Innings (1982), Season Ticket (1988), and Once More Around the Park (1991). I own all of them, and have read them multiple times. “Aha!!” I was able to reply. “What about Joe Morgan? Two time Most Valuable Player, perennial All-Star, World Series champion. He’s five foot seven!” Besides, I assured them. I didn’t expect or need to be six feet tall. I would be perfectly happy with five foot ten, like my hero, Roy White.

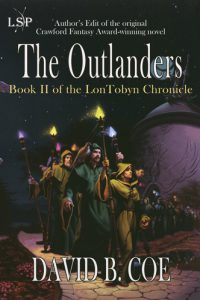

“Aha!!” I was able to reply. “What about Joe Morgan? Two time Most Valuable Player, perennial All-Star, World Series champion. He’s five foot seven!” Besides, I assured them. I didn’t expect or need to be six feet tall. I would be perfectly happy with five foot ten, like my hero, Roy White. Favorite of My Books: The most recent one I’ve written, almost always. Which is a copout, I know. Invasives, the second Radiants book, comes out in February, so it is the most recent I’ve written, and it is my current favorite. But in another way, my favorite is probably The Outlanders, the second book in my LonTobyn Chronicle, and my second novel overall. Why? Simple. When I began my career, I knew I had one book in me, but I didn’t know if I could write for a living. Upon finishing The Outlanders, I realized it was better than my first book, Children of Amarid, a book of which I was quite proud. It was much better, in fact. And I understood then that I was not just a guy who wrote a book. I was an author. I could make a career of this.

Favorite of My Books: The most recent one I’ve written, almost always. Which is a copout, I know. Invasives, the second Radiants book, comes out in February, so it is the most recent I’ve written, and it is my current favorite. But in another way, my favorite is probably The Outlanders, the second book in my LonTobyn Chronicle, and my second novel overall. Why? Simple. When I began my career, I knew I had one book in me, but I didn’t know if I could write for a living. Upon finishing The Outlanders, I realized it was better than my first book, Children of Amarid, a book of which I was quite proud. It was much better, in fact. And I understood then that I was not just a guy who wrote a book. I was an author. I could make a career of this.

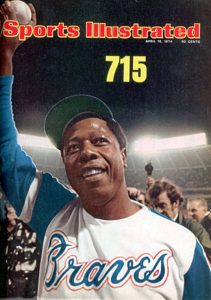

I was watching that night, along with pretty much every other eleven year-old, baseball-loving boy in America. I remember everything about it — the call from announcer Vin Scully, the twist and high stare of Dodgers pitcher Al Downing as he watched the ball sail out over left field, Aaron’s joyful trot around the bases, the two white guys in civilian clothes who appeared out of nowhere as he rounded second base and patted his back and shoulder, the way his jubilant teammates mobbed him at home plate and put him on their shoulders. I still have the issue of Sports Illustrated from the next week, with Aaron on the cover holding up the baseball next to a golden, bolded “715.” And I also still have the special edition baseball card Topps issued that same year proclaiming Aaron baseball’s home run king.

I was watching that night, along with pretty much every other eleven year-old, baseball-loving boy in America. I remember everything about it — the call from announcer Vin Scully, the twist and high stare of Dodgers pitcher Al Downing as he watched the ball sail out over left field, Aaron’s joyful trot around the bases, the two white guys in civilian clothes who appeared out of nowhere as he rounded second base and patted his back and shoulder, the way his jubilant teammates mobbed him at home plate and put him on their shoulders. I still have the issue of Sports Illustrated from the next week, with Aaron on the cover holding up the baseball next to a golden, bolded “715.” And I also still have the special edition baseball card Topps issued that same year proclaiming Aaron baseball’s home run king. Still, I can say this: It’s easy to grow attached to one particular franchise, one particularly world and set of characters and style of story. Certainly I have written a good deal in the Thieftaker world, and will soon be coming out with new work about Ethan Kaille, Sephira Pryce, et al. The fact is, though, each time I have moved on to a new project, I have tried (admittedly with varying degrees of success) to challenge myself, to force myself to grow.

Still, I can say this: It’s easy to grow attached to one particular franchise, one particularly world and set of characters and style of story. Certainly I have written a good deal in the Thieftaker world, and will soon be coming out with new work about Ethan Kaille, Sephira Pryce, et al. The fact is, though, each time I have moved on to a new project, I have tried (admittedly with varying degrees of success) to challenge myself, to force myself to grow. After the LonTobyn books, I moved to Winds of the Forelands and Blood of the Southlands, which demanded far more sophisticated world building and character work. After those, I turned to Thieftaker, adding historical and mystery elements to my storytelling and limiting my point of view to a single character. I also started working on the Justis Fearsson books, which explored mental health issues and were my first forays into writing in a contemporary setting. Then I took on the Islevale books, time travel/epic fantasies that presented the most difficult plotting issues I’ve ever faced.

After the LonTobyn books, I moved to Winds of the Forelands and Blood of the Southlands, which demanded far more sophisticated world building and character work. After those, I turned to Thieftaker, adding historical and mystery elements to my storytelling and limiting my point of view to a single character. I also started working on the Justis Fearsson books, which explored mental health issues and were my first forays into writing in a contemporary setting. Then I took on the Islevale books, time travel/epic fantasies that presented the most difficult plotting issues I’ve ever faced.