This post is not about my daughters. I swear. I love my girls exactly the same amount. Except maybe around my birthday, when my love for them is directly proportional to the quality of the presents they give me. Other than that, though, I don’t play favorites.

Today, I am writing about my other babies. My books.

I am asked quite often if I have a favorite among the books or series I’ve written, and always I deflect a bit. I make a joke about how my books are like my children and asking me to choose among them is akin to asking me which of my kids I love most. Then I say something about how, generally speaking, my favorite book is my newest book. And there is some truth to that. I am still learning, still honing my skills as a storyteller and a writer. I believe my books continue to improve.

It is also true, though, that I do have favorites. Probably not one overall favorite in particular (although I do have a candidate for that — more later!) but there are certain books that I love more than some of the others. To be clear, I am proud of all my books. I like them all. Otherwise I wouldn’t have written them. But yeah, I have favorites.

I’ve been thinking of this a lot recently because I am in the process — finally! — of reissuing my Winds of the Forelands series, which has been out of print for several years. The books are currently being scanned digitally (they are old enough that I never had digital files of the final — copy edited and proofed — versions of the books) and once that process is done, I will edit and polish them and find some way to put them out into the world again.

I’ve been thinking of this a lot recently because I am in the process — finally! — of reissuing my Winds of the Forelands series, which has been out of print for several years. The books are currently being scanned digitally (they are old enough that I never had digital files of the final — copy edited and proofed — versions of the books) and once that process is done, I will edit and polish them and find some way to put them out into the world again.

I have always viewed the Forelands series as the most important project of my career. I’ve done better work since, but Winds of the Forelands marked a huge step forward from my first series, the LonTobyn Chronicle. The Forelands books proved to me (and to my publisher) that I could not only come up with another world, another narrative, another set of characters, but I could do all of those things with greater creativity and to greater effect than I had with the first series. For that reason alone, Winds of the Forelands is among my favorites of all the series I’ve written.

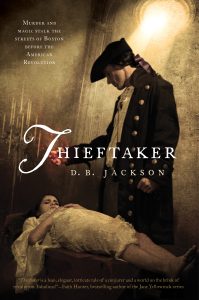

I should pause here to say again that I love all my books and I am deeply proud of lots of the books fans of my work like best. The Thieftaker books, for instance — I love writing them, I look forward to writing more of them. I think the concept for the series is clearly the best I’ve ever developed; there’s a reason those are my most popular stories. There’s also a reason why I’ve written more books (6) and more short stories (at least 12) in that world than in any other.

That said, the books that tend to be my favorites are ones that have special emotional resonance for me. My choices in this regard have almost nothing to do with sales or critical success and everything to do with my attachment to the characters and the worlds, or in a couple of cases, with what was happening in my private life when I wrote the books. I would even go so far as to say that I love some books precisely because they have not done as well commercially as others. It’s as if I am compensating in a way, giving them extra love to make up for the fact that they failed to garner the attention I believe they deserve.

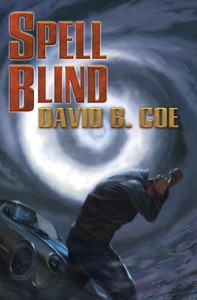

I feel that way about the second and third books in my Case Files of Justis Fearsson series, His Father’s Eyes and Shadow’s Blade. These books are easily as good as the best Thieftaker books, but the Fearsson series, for whatever reason, never took off the way Thieftaker did. Hence, few people know about the Fearsson books, and it’s a shame, because these two volumes especially include some of the best writing I’ve ever done.

I feel that way about the second and third books in my Case Files of Justis Fearsson series, His Father’s Eyes and Shadow’s Blade. These books are easily as good as the best Thieftaker books, but the Fearsson series, for whatever reason, never took off the way Thieftaker did. Hence, few people know about the Fearsson books, and it’s a shame, because these two volumes especially include some of the best writing I’ve ever done.

Same with the Islevale Cycle trilogy. Time’s Children is the best reviewed book I’ve written, and Time’s Demon and Time’s Assassin build on the work I did in that first volume. But the books did poorly commercially because the series got lost in a complete reshuffling of the management and staffing of the company that published the first two installments. The series died before it ever had a chance to succeed. Which is a shame, because the world building I did for Islevale is my best by a country mile, and the plotting is the most ambitious and complex I ever attempted. Those three novels are certainly among my very favorites.

Same with the Islevale Cycle trilogy. Time’s Children is the best reviewed book I’ve written, and Time’s Demon and Time’s Assassin build on the work I did in that first volume. But the books did poorly commercially because the series got lost in a complete reshuffling of the management and staffing of the company that published the first two installments. The series died before it ever had a chance to succeed. Which is a shame, because the world building I did for Islevale is my best by a country mile, and the plotting is the most ambitious and complex I ever attempted. Those three novels are certainly among my very favorites.

But of all the novels I have published thus far, my favorite is Invasives, the second Radiants book. As I have mentioned here before, Invasives saved me. This was the book I was writing when our older daughter received her cancer diagnosis. I briefly shelved the project, thinking I couldn’t possible write while in the midst of that crisis. I soon realized, however, that I HAD to write, that writing would keep me centered and sane. I believe pouring all my emotional energy into the book explains why Invasives contains far and away the best character work I have ever done. It’s also paced better than any book I’ve written. It is simply my best.

But of all the novels I have published thus far, my favorite is Invasives, the second Radiants book. As I have mentioned here before, Invasives saved me. This was the book I was writing when our older daughter received her cancer diagnosis. I briefly shelved the project, thinking I couldn’t possible write while in the midst of that crisis. I soon realized, however, that I HAD to write, that writing would keep me centered and sane. I believe pouring all my emotional energy into the book explains why Invasives contains far and away the best character work I have ever done. It’s also paced better than any book I’ve written. It is simply my best.

So far.

Next month, I will release the first volume of The Chalice War trilogy, my Celtic urban fantasy. This is a different sort of book for me, a different sort of series. As usual with a new release, I love the book and I am excited to get it into the hands of my readers.

Next month, I will release the first volume of The Chalice War trilogy, my Celtic urban fantasy. This is a different sort of book for me, a different sort of series. As usual with a new release, I love the book and I am excited to get it into the hands of my readers.

Do I think it’s my best? Honestly, it’s too early to say. It has more humor than anything I’ve ever written, and I’m very proud of the way I have adapted Celtic lore to our modern world. Plus, I love my characters. So yeah, I love it. Do I love it most? Time will tell.

Have a great week!

We kept the site going for nearly a decade (thanks Todd Massey), and the site still exists, for those interested in wading through the extensive archives. We also produced a writing book, which is still available.

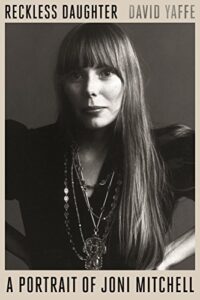

We kept the site going for nearly a decade (thanks Todd Massey), and the site still exists, for those interested in wading through the extensive archives. We also produced a writing book, which is still available. Recently, I have been reading a biography of Joni Mitchell (a holiday gift from my older daughter), a long-time favorite of mine and, in my opinion, the finest songwriter in the history of rock and roll (more on that shortly). It’s been an interesting read — the author is a bit fawning for my taste, and a bit too eager as well to weave Mitchell’s (admittedly phenomenal) lyrics into his prose. But as is often the case when I read biographies of artists I admire, the book made me think about creativity and the artistic process.

Recently, I have been reading a biography of Joni Mitchell (a holiday gift from my older daughter), a long-time favorite of mine and, in my opinion, the finest songwriter in the history of rock and roll (more on that shortly). It’s been an interesting read — the author is a bit fawning for my taste, and a bit too eager as well to weave Mitchell’s (admittedly phenomenal) lyrics into his prose. But as is often the case when I read biographies of artists I admire, the book made me think about creativity and the artistic process. My “What matters?” series of posts will conclude next Monday, after a Monday Musings post this week that straddled the personal and professional a bit more than usual. In the meantime, I am using today’s Professional Wednesday post to begin pivoting toward the impending release of my new series, a contemporary urban fantasy that delves deeply into Celtic mythology. The series is called The Chalice War, and the first book is The Chalice War: Stone. It will be released within the next month or so, and will be followed soon after by the second book, The Chalice War: Cauldron, and the finale, The Chalice War: Sword.

My “What matters?” series of posts will conclude next Monday, after a Monday Musings post this week that straddled the personal and professional a bit more than usual. In the meantime, I am using today’s Professional Wednesday post to begin pivoting toward the impending release of my new series, a contemporary urban fantasy that delves deeply into Celtic mythology. The series is called The Chalice War, and the first book is The Chalice War: Stone. It will be released within the next month or so, and will be followed soon after by the second book, The Chalice War: Cauldron, and the finale, The Chalice War: Sword. I finished the book and showed it to my agent. She liked it a lot, but thought it needed work. She was right, of course. But by that time, I had signed the contracts for Robin Hood and the Thieftaker books. Not too long after, I finally sold the Fearsson series to Baen Books and so had that trilogy to get through.

I finished the book and showed it to my agent. She liked it a lot, but thought it needed work. She was right, of course. But by that time, I had signed the contracts for Robin Hood and the Thieftaker books. Not too long after, I finally sold the Fearsson series to Baen Books and so had that trilogy to get through. But I never forgot my Celtic urban fantasy, or its heroes Marti and Kel. When I had some spare time, I went back and rewrote the book, incorporating revision notes from friends and from my agent with my own sense of what the book needed. I rewrote it a second time a couple of years later, and having some time, started work on a second volume, this one set in Australia (where my family and I lived in 2005-2006). I stalled out on that book about two-thirds of the way in, but I liked what I had. By then, though, I was deeply involved with the final Thieftaker books and the Fearsson series. And I was starting to have some ideas for what would become the Islevale trilogy.

But I never forgot my Celtic urban fantasy, or its heroes Marti and Kel. When I had some spare time, I went back and rewrote the book, incorporating revision notes from friends and from my agent with my own sense of what the book needed. I rewrote it a second time a couple of years later, and having some time, started work on a second volume, this one set in Australia (where my family and I lived in 2005-2006). I stalled out on that book about two-thirds of the way in, but I liked what I had. By then, though, I was deeply involved with the final Thieftaker books and the Fearsson series. And I was starting to have some ideas for what would become the Islevale trilogy. What are you giving for the holidays?

What are you giving for the holidays? May I suggest a book, or several books?

May I suggest a book, or several books? Yes, I know, this probably seems a little crass. But here’s the thing: Creators like me make our livings off the sale of our creations. It really is that simple. If our books (or music or art or whatever) don’t sell, we don’t earn.

Yes, I know, this probably seems a little crass. But here’s the thing: Creators like me make our livings off the sale of our creations. It really is that simple. If our books (or music or art or whatever) don’t sell, we don’t earn. Now, many of you are probably saying at this point that you have already bought my books and, I hope, read and enjoyed them. That’s wonderful. Thank you. Truly.

Now, many of you are probably saying at this point that you have already bought my books and, I hope, read and enjoyed them. That’s wonderful. Thank you. Truly. Around that same time, I was also reading submissions for the Temporally Deactivated anthology, my first co-editing venture. Last year I opened my freelance editing business, and a year ago at this time, I was editing a manuscript for a client.

Around that same time, I was also reading submissions for the Temporally Deactivated anthology, my first co-editing venture. Last year I opened my freelance editing business, and a year ago at this time, I was editing a manuscript for a client. Last week, I wrote about planning out my professional activities for the coming year. This week, I want to discuss a different element of professional planning. My point in starting off with a list of those projects from past years is that just about every year, I try to take on a new challenge, something I’ve never attempted before. I didn’t start off doing this consciously — I didn’t say to myself, “I’m going to start doing something new each year, just to shake things up.” It just sort of happened.

Last week, I wrote about planning out my professional activities for the coming year. This week, I want to discuss a different element of professional planning. My point in starting off with a list of those projects from past years is that just about every year, I try to take on a new challenge, something I’ve never attempted before. I didn’t start off doing this consciously — I didn’t say to myself, “I’m going to start doing something new each year, just to shake things up.” It just sort of happened. As it turns out, these new challenges have brought me to a place where I can say, in all candor, that I have never been happier in my work than I am now. Each time I try something new, I reinvigorate myself as a creator. I force myself out of the tried-and-true, the comfortable. With each of the new projects I mentioned above I had a moment of doubt. I wondered if I was capable of accomplishing what I set out to do. Now, I’m a pretty confident guy when it comes to my writing chops and my ability to help others improve their writing, so those doubts didn’t last long. But they were there each time.

As it turns out, these new challenges have brought me to a place where I can say, in all candor, that I have never been happier in my work than I am now. Each time I try something new, I reinvigorate myself as a creator. I force myself out of the tried-and-true, the comfortable. With each of the new projects I mentioned above I had a moment of doubt. I wondered if I was capable of accomplishing what I set out to do. Now, I’m a pretty confident guy when it comes to my writing chops and my ability to help others improve their writing, so those doubts didn’t last long. But they were there each time. But those new challenges did more than that. They kept my professional routine fresh. I am a creature of habit. I try to write/edit/work every day, so in a general sense, my work days and work weeks don’t change all that much. By varying the content of my job — by writing new kinds of stories and expanding my professional portfolio to include editing as well as writing — I made the routine feel new and shiny and exciting. And at the same time, these new projects made it possible to return to some old favorites, notably the Thieftaker series, with renewed enthusiasm.

But those new challenges did more than that. They kept my professional routine fresh. I am a creature of habit. I try to write/edit/work every day, so in a general sense, my work days and work weeks don’t change all that much. By varying the content of my job — by writing new kinds of stories and expanding my professional portfolio to include editing as well as writing — I made the routine feel new and shiny and exciting. And at the same time, these new projects made it possible to return to some old favorites, notably the Thieftaker series, with renewed enthusiasm.