Today, I’m introducing a new feature for my Professional Wednesday posts: “Most Important Lessons.”

We are coming up on the 28th anniversary of the start of my career (which I trace to the offer I received from Tor Books on Children of Amarid, my first novel). To mark the occasion, I thought about doing a “lessons I’ve learned” post. I quickly realized, though, that I could write 20,000 words on that and still not exhaust the topic. Better then, to begin this series of essays, which I will return to periodically, as I think of key lessons that I’ve learned about the business and craft of writing.

I’ve chosen to start with today’s lesson — “Trust Yourself, Trust Your Reader” — because it’s one I’ve found myself repeating to writers a lot as I edit short stories for the Noir anthology and novel length projects that come to me through my freelance editing business.

Honestly, I think “trust yourself” is good advice for life in general, but for me, with respect to writing, it has a specific implication. It’s something I heard a lot from my first editor when I was working on my earliest series — the LonTobyn Chronicle and Winds of the Forelands.

Honestly, I think “trust yourself” is good advice for life in general, but for me, with respect to writing, it has a specific implication. It’s something I heard a lot from my first editor when I was working on my earliest series — the LonTobyn Chronicle and Winds of the Forelands.

Writers, and in particular less experienced writers, have a tendency to tell readers too much. Sometimes this manifests in data dumps, where we give way more information about our worlds or our characters than is necessary. And yes, that can be a problem. I have no doubt that in future “Most Important Lessons” posts, I will cover world building, character, and ways to avoid data dumps.

For today’s purposes, though, I refer to a different sort of writing problem that can be solved simply by trusting our readers and trusting ourselves. As I said, writers often tell readers too much. We explain things — plot points, narrative situations, personality traits. And then we tell them again. And again. And as we build to our key narrative moments, we give that information yet again, wanting to make certain that our readers are set up for the resolutions we’re about to provide.

There are several problems with doing this. First, it tends to make our writing repetitive, wordy, and slow. Nobody wants to read the same information over and over. It’s boring; worse, it’s annoying. Second, it forces us to hit the brakes at those moments when we should be most eager to keep things moving. If we’re explaining stuff as we approach the climactic scenes in our stories, we are undermining our pacing, weakening our storytelling, robbing our stories of tension and suspense. And third, we are denying our readers the pleasure of making connections on their own. We are, in a way, being like that guy in the movie theater revealing key moments in the film right before they happen on screen. And everyone hates that guy.

We have to trust that our readers have retained the things we’ve told them. We have to trust that they are following along as we fill in backstory, set up our key plot points, and build our character arcs and narrative arcs. We have to trust that they are right there with us as we move through our plots.

In other words, we have to trust that we have done our jobs as writers.

Trusting our readers means trusting ourselves. Readers are smart. They pay attention. They read our stories and books because they want to. Sure, sometimes they miss things. Sometimes they skim when they ought to be paying attention. As a reader myself, I know that I am not always as attentive as I ought to be. But I also know that when I sense I’ve missed something important, I go back and reread the sections in question. Your readers will do the same.

Trust that you have engaged them with your plot lines and characters. Trust that you have given them the information they need to follow along, and have built your stories the way you ought to. Trust that they are following the path you’ve blazed for them.

“But,” you say, “what if I haven’t done those things? Isn’t it better to be certain, to tell them more than they need to know, so that I can be absolutely sure they get it?”

It would seem that way, wouldn’t it? But that’s where trust comes in. Sure, there is a balance to be found. We don’t want to give our readers too much, but we don’t want them to have too little, either. And the vast majority of us fear the latter far more than the former. We shouldn’t. Again, readers are pretty smart. If the information is in the book, they’ll make use of it. Better, then, to trust, to say, “It’s in there. I’ve done what I could, what I had to. I am going to trust that I did enough.”

Yes, the first time or two, we might need to revise and give another hint here or there. But generally speaking, when we trust our readers — when we trust ourselves — we avoid far more problems than we create.

Trust me.

Keep writing.

The Outlanders, my second book, may well be the most significant of all the books I’ve published. I knew I had it in me to write one book. But when I finished The Outlanders, and realized it was even better than CofA, I knew I was more than a guy who could write a novel. I was an author. And when Children of Amarid and The Outlanders together were given the Crawford Fantasy Award by the IAFA (International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts), for best fantasy by a new writer, I knew I would have a professional career beyond that first series.

The Outlanders, my second book, may well be the most significant of all the books I’ve published. I knew I had it in me to write one book. But when I finished The Outlanders, and realized it was even better than CofA, I knew I was more than a guy who could write a novel. I was an author. And when Children of Amarid and The Outlanders together were given the Crawford Fantasy Award by the IAFA (International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts), for best fantasy by a new writer, I knew I would have a professional career beyond that first series. I did just that. I started with some short stories that have never since seen the light of day, but which helped me to shape the contours of my world and its history. Then I began work on the novel, and by September had completed the first five chapters of what would eventually be Children of Amarid, my first published novel. I gave the manuscript to a friend of the family who had been a publisher, and he agreed to act as my agent, operating under standard agenting fees. He sent those five chapters and an outline of the rest of the book to various fantasy publishers.

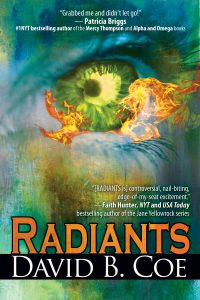

I did just that. I started with some short stories that have never since seen the light of day, but which helped me to shape the contours of my world and its history. Then I began work on the novel, and by September had completed the first five chapters of what would eventually be Children of Amarid, my first published novel. I gave the manuscript to a friend of the family who had been a publisher, and he agreed to act as my agent, operating under standard agenting fees. He sent those five chapters and an outline of the rest of the book to various fantasy publishers. Last week, I was able to share with you the incredible art work for my upcoming novel, Invasives, the second Radiants book, which will be out February 18. And because I’m mentioning the art here, I have yet another excuse to post the image, which I love and will share for even the most contrived of reasons . . .

Last week, I was able to share with you the incredible art work for my upcoming novel, Invasives, the second Radiants book, which will be out February 18. And because I’m mentioning the art here, I have yet another excuse to post the image, which I love and will share for even the most contrived of reasons . . . For the Thieftaker novels, Tor hired the incomparable

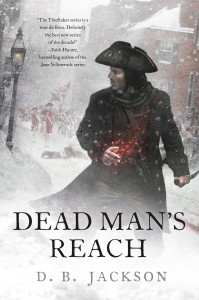

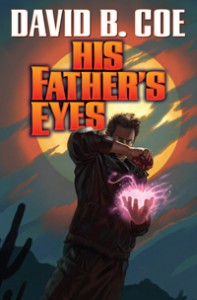

For the Thieftaker novels, Tor hired the incomparable  The thing to remember about artwork, though, is that it’s not enough for the covers to be eye-catching. They also need to tell a story — your story. The Thieftaker covers work because they convey the time period, they offer a suggestion of the mystery contained within, and they hint as well at magic, by always including that swirl of conjuring power in Ethan’s hand. The Islevale covers all have that golden timepiece in them, the chronofor, which enables my Walkers to move through time. All my traditional epic fantasy covers, from the LonTobyn books through the Forelands and Southlands series, convey a medieval fantasy vibe. Readers who see those books, even if they don’t know me or my work, will have an immediate sense of the stories contained within.

The thing to remember about artwork, though, is that it’s not enough for the covers to be eye-catching. They also need to tell a story — your story. The Thieftaker covers work because they convey the time period, they offer a suggestion of the mystery contained within, and they hint as well at magic, by always including that swirl of conjuring power in Ethan’s hand. The Islevale covers all have that golden timepiece in them, the chronofor, which enables my Walkers to move through time. All my traditional epic fantasy covers, from the LonTobyn books through the Forelands and Southlands series, convey a medieval fantasy vibe. Readers who see those books, even if they don’t know me or my work, will have an immediate sense of the stories contained within. And that’s what we want. Sure, part of what makes that Invasives cover work is the simple fact that it’s stunning. The eye, the flames, the lighting in the tunnel. It’s a terrific image. But it also tells you there is a supernatural story within. And while the tunnel “setting” is unusual, the presence of train tracks, wires, electric wiring, and even that loudspeaker in the upper left quadrant of the tunnel, combine to tell you the story takes place in our world (or something very much like it). And for those who have seen the cover of the first book in the series, Radiants, the eye and flames mark this new book as part of the same franchise. That’s effective packaging.

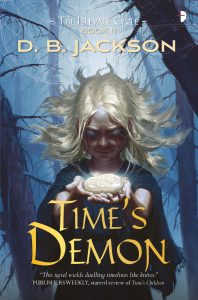

And that’s what we want. Sure, part of what makes that Invasives cover work is the simple fact that it’s stunning. The eye, the flames, the lighting in the tunnel. It’s a terrific image. But it also tells you there is a supernatural story within. And while the tunnel “setting” is unusual, the presence of train tracks, wires, electric wiring, and even that loudspeaker in the upper left quadrant of the tunnel, combine to tell you the story takes place in our world (or something very much like it). And for those who have seen the cover of the first book in the series, Radiants, the eye and flames mark this new book as part of the same franchise. That’s effective packaging. In the same vein, poor marketing practices by a publisher, even if inadvertent, can doom even the most beautiful book. I LOVE the art for Time’s Demon, the second Islevale novel. But the novel came out when the publisher was going through an intense reorganization. It got little or no marketing attention, and despite looking great and being in my view one of the best things I’ve written, it was pretty much the worst-selling book of my career.

In the same vein, poor marketing practices by a publisher, even if inadvertent, can doom even the most beautiful book. I LOVE the art for Time’s Demon, the second Islevale novel. But the novel came out when the publisher was going through an intense reorganization. It got little or no marketing attention, and despite looking great and being in my view one of the best things I’ve written, it was pretty much the worst-selling book of my career.

Still, I can say this: It’s easy to grow attached to one particular franchise, one particularly world and set of characters and style of story. Certainly I have written a good deal in the Thieftaker world, and will soon be coming out with new work about Ethan Kaille, Sephira Pryce, et al. The fact is, though, each time I have moved on to a new project, I have tried (admittedly with varying degrees of success) to challenge myself, to force myself to grow.

Still, I can say this: It’s easy to grow attached to one particular franchise, one particularly world and set of characters and style of story. Certainly I have written a good deal in the Thieftaker world, and will soon be coming out with new work about Ethan Kaille, Sephira Pryce, et al. The fact is, though, each time I have moved on to a new project, I have tried (admittedly with varying degrees of success) to challenge myself, to force myself to grow. After the LonTobyn books, I moved to Winds of the Forelands and Blood of the Southlands, which demanded far more sophisticated world building and character work. After those, I turned to Thieftaker, adding historical and mystery elements to my storytelling and limiting my point of view to a single character. I also started working on the Justis Fearsson books, which explored mental health issues and were my first forays into writing in a contemporary setting. Then I took on the Islevale books, time travel/epic fantasies that presented the most difficult plotting issues I’ve ever faced.

After the LonTobyn books, I moved to Winds of the Forelands and Blood of the Southlands, which demanded far more sophisticated world building and character work. After those, I turned to Thieftaker, adding historical and mystery elements to my storytelling and limiting my point of view to a single character. I also started working on the Justis Fearsson books, which explored mental health issues and were my first forays into writing in a contemporary setting. Then I took on the Islevale books, time travel/epic fantasies that presented the most difficult plotting issues I’ve ever faced.

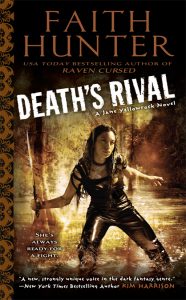

In the same way, action scenes – fight scenes, battle scenes, violent scenes; whatever you want to call them – also hinge on the qualities, histories, experiences, and emotions of our point of view characters. A seasoned fighter, someone who makes their living in a violent world or who was brought up to be a warrior, is going to experience violence quite differently from, well, someone like me, who has little knowledge of fighting technique and scant history with violence and bloodshed. The practiced fighter’s point of view might sound almost clinical – this person will know how to control emotion, how to draw upon skills and observations learned over years of training. The novice’s point of view should come off as far more desperate, fearful, overwhelmed by the frenzy of violence in which they find themselves. Again, point of view is all. One is not necessarily more exciting to read than the other – think of the battle scenes in Faith Hunter’s thrilling, New York Times Bestselling Jane Yellowrock books and in A.J. Hartley’s wonderful Will Hawthorne novels, which are not only entertaining but also a master class in writing voice. Jane is a warrior; Will is SO not.. The scenes in both make for compelling reading, but they couldn’t be more different.

In the same way, action scenes – fight scenes, battle scenes, violent scenes; whatever you want to call them – also hinge on the qualities, histories, experiences, and emotions of our point of view characters. A seasoned fighter, someone who makes their living in a violent world or who was brought up to be a warrior, is going to experience violence quite differently from, well, someone like me, who has little knowledge of fighting technique and scant history with violence and bloodshed. The practiced fighter’s point of view might sound almost clinical – this person will know how to control emotion, how to draw upon skills and observations learned over years of training. The novice’s point of view should come off as far more desperate, fearful, overwhelmed by the frenzy of violence in which they find themselves. Again, point of view is all. One is not necessarily more exciting to read than the other – think of the battle scenes in Faith Hunter’s thrilling, New York Times Bestselling Jane Yellowrock books and in A.J. Hartley’s wonderful Will Hawthorne novels, which are not only entertaining but also a master class in writing voice. Jane is a warrior; Will is SO not.. The scenes in both make for compelling reading, but they couldn’t be more different.