After publishing my review of Guy Gavriel Kay’s marvelous new book, All the Seas of the World (coming from Viking Press on May 17), the good people at Black Gate Magazine approached me about writing more reviews for them, something I am excited to do. So, going forward, in addition to being an author and editor, I will also be a reviewer.

After publishing my review of Guy Gavriel Kay’s marvelous new book, All the Seas of the World (coming from Viking Press on May 17), the good people at Black Gate Magazine approached me about writing more reviews for them, something I am excited to do. So, going forward, in addition to being an author and editor, I will also be a reviewer.

In my discussions with the wonderful John O’Neill, Black Gate’s award-winning editor, I made it clear that I would write honest reviews on a spectrum ranging from “this is a pretty good book” to “this is the finest book I’ve ever read.” But I would not write any negative reviews. John agreed, telling me this was just the approach he was after. And yet to many, that might seem like an odd approach to reviewing books, and so I feel it’s a position that bears explaining.

I believe reviews are most valuable when they point readers in the direction of something they might enjoy. I understand there are certain publications — Publisher’s Weekly and Kirkus Reviews come to mind — that are expected to review a wide range of books and distinguish the good from the bad. By necessity, such venues have to give some negative reviews. Indeed, early in my career I was on the receiving end of several such critiques. It’s part of the business. In a sense, with publications like those, the bad reviews actually lend legitimacy and weight to the good ones.

Black Gate Magazine, and other journals of its kind, are not like that. They do not review comprehensively. They pick out a few books in the genre and shine a spotlight on them. In effect, they say, “Hey, fantasy readers! Here are a couple of books you should check out, not to the exclusion of others necessarily, but simply because they are particularly good.” For a venue like Black Gate, writing and publishing a negative review would be gratuitous. It would be an act of singling out one book for disparagement and ridicule.

As I said to John during our discussion, I have no interest in hurting someone’s career. If he and his staff send me a book to review and I don’t like it, we will simply keep that opinion to ourselves. There’s no need to pan it; we just won’t be recommending it. Because the fact is, just because I don’t like a novel, that doesn’t mean it’s bad. I’m only one reader. My not liking a book simply means . . . I didn’t like it. Period. Full stop.

I feel quite strongly about this, because I have been on the receiving end of a gratuitously scathing review.

Yes, I know: There are unwritten rules pertaining to writers and professional critiques of our books. Writers aren’t supposed to read our reviews. Newsflash: We do anyway. Writers are supposed to ignore bad reviews. It’s harder to do than you might imagine. If writers are going to read our reviews and not ignore them, we should internalize the good ones and shrug off the bad ones. That might be even harder than ignoring them.

And as it happens, the review in question was the perfect storm of ugliness. First, it was about a book I loved and know was good. Sure, it had flaws; show me a book that doesn’t. But it was a quality book and it certainly didn’t deserve the treatment it received. Second, the review was in a high profile publication. Lots of people saw it. Third, I have good reason to believe the reviewer, with whom I had a bit of history, was acting out of personal animus. The criticism was savage and it was presented in such a way as to be especially humiliating. I won’t say more than that.

Except this. The review hurt. It sent me into a professional tailspin that lasted months. That dark period is long since over, so I am not seeking sympathy. But at the time, it did some damage to my psyche and to my creative output. And there was no reason for it. They didn’t like the book. Fine. Then ignore it. Don’t give it the benefit of a positive spotlight.

They went further. Again, fine. That’s their choice.

I will take a different tack. If I like a book I will publish a review saying so. If I don’t, if for some reason the book doesn’t excite me, or it rubs me the wrong way, I will set it aside without public comment and move on to the next.

Other reviewers are, of course, free to take a different approach. I will not judge them. But I want to write reviews for the fun of it, for the satisfaction of sharing with others my perceptions of an entertaining or moving or thrilling reading experience. I’m not interested in hurting anyone.

Keep writing!

And when it comes to writing, I am in something of a rut. The last novel-length piece I wrote beginning to end was Invasives, the second Radiants book, which I completed (the first draft at least) eleven months ago. Eleven months!

And when it comes to writing, I am in something of a rut. The last novel-length piece I wrote beginning to end was Invasives, the second Radiants book, which I completed (the first draft at least) eleven months ago. Eleven months! Mostly, as I say, I’ve been editing. My work. Other people’s work. The Noir anthology. I’ve been plenty busy, but I have not been as productive creatively as I would like. And I wonder if this is because of

Mostly, as I say, I’ve been editing. My work. Other people’s work. The Noir anthology. I’ve been plenty busy, but I have not been as productive creatively as I would like. And I wonder if this is because of  But at the very least, we need to see our main heroes grappling with what they have endured and setting their sights on what is next for them. We don’t need this for every character but we need it for the key ones. Ask yourself, “whose book is this?” For me, this is sometimes quite clear. With the Thieftaker books, every story is Ethan’s. And so I let my readers see Ethan settling back into life with Kannice and making a new, fragile peace with Sephira, or something like that. With other projects, though, “Whose book is this?” can be more complicated. In the Islevale books — my time travel/epic fantasy trilogy — I needed to tie off the loose ends of several plot threads: Tobias and Mara, Droë, and a few others. Each had their “Louis” moment at the end of the last book, and also some sense of closure at the ends of the first two volumes.

But at the very least, we need to see our main heroes grappling with what they have endured and setting their sights on what is next for them. We don’t need this for every character but we need it for the key ones. Ask yourself, “whose book is this?” For me, this is sometimes quite clear. With the Thieftaker books, every story is Ethan’s. And so I let my readers see Ethan settling back into life with Kannice and making a new, fragile peace with Sephira, or something like that. With other projects, though, “Whose book is this?” can be more complicated. In the Islevale books — my time travel/epic fantasy trilogy — I needed to tie off the loose ends of several plot threads: Tobias and Mara, Droë, and a few others. Each had their “Louis” moment at the end of the last book, and also some sense of closure at the ends of the first two volumes. Why do I do this? Why am I suggesting you do it, too? Because while we are telling stories, our books are about more than plot, more than action and intrigue and suspense. Our books are about people. Not humans, necessarily, but people certainly. If we do our jobs as writers, our readers will be absorbed by our narratives, but more importantly, they will become attached to our characters. And they will want to see more than just the big moment when those characters prevail (or not). They will want to see a bit of what comes after.

Why do I do this? Why am I suggesting you do it, too? Because while we are telling stories, our books are about more than plot, more than action and intrigue and suspense. Our books are about people. Not humans, necessarily, but people certainly. If we do our jobs as writers, our readers will be absorbed by our narratives, but more importantly, they will become attached to our characters. And they will want to see more than just the big moment when those characters prevail (or not). They will want to see a bit of what comes after. Honestly, I think “trust yourself” is good advice for life in general, but for me, with respect to writing, it has a specific implication. It’s something I heard a lot from my first editor when I was working on my earliest series — the LonTobyn Chronicle and Winds of the Forelands.

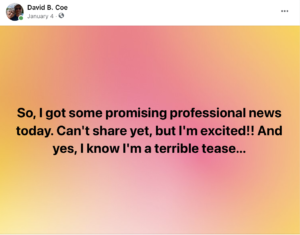

Honestly, I think “trust yourself” is good advice for life in general, but for me, with respect to writing, it has a specific implication. It’s something I heard a lot from my first editor when I was working on my earliest series — the LonTobyn Chronicle and Winds of the Forelands. Nearly two months ago, early in the new year, I posted on social media that I had some exciting professional news I couldn’t share quite yet. I was thrilled, and wanted to let people know. But I also didn’t want to say anything before all the details had been settled. So I posted my little teaser, forgetting the one immutable rule of the publishing business: Things always happen slower than one thinks they will.

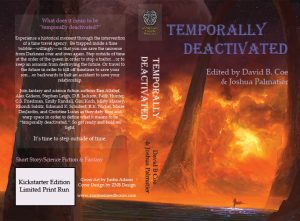

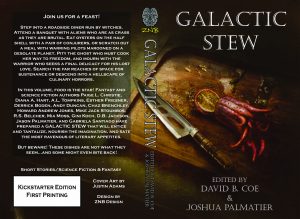

Nearly two months ago, early in the new year, I posted on social media that I had some exciting professional news I couldn’t share quite yet. I was thrilled, and wanted to let people know. But I also didn’t want to say anything before all the details had been settled. So I posted my little teaser, forgetting the one immutable rule of the publishing business: Things always happen slower than one thinks they will. Since writing it, though, I have become sort of fixated on the idea. I am editing my fourth anthology, and already looking at the possibility of editing another. My freelance editing business is attracting a steady stream of clients — I’m booked through the spring and have had inquiries for slots later in the year.

Since writing it, though, I have become sort of fixated on the idea. I am editing my fourth anthology, and already looking at the possibility of editing another. My freelance editing business is attracting a steady stream of clients — I’m booked through the spring and have had inquiries for slots later in the year. I am not an acquiring editor. I do decide, along with my co-editor, whose stories will be in the anthologies I edit, so I suppose in that way I am determining the fate of submissions and, in a sense, “buying” manuscripts. But, for now at least, I don’t make decisions about the fate of novels, and so I don’t have to go toe-to-toe with agents. Good thing. They scare me. (Looking at you, Lucienne Diver.)

I am not an acquiring editor. I do decide, along with my co-editor, whose stories will be in the anthologies I edit, so I suppose in that way I am determining the fate of submissions and, in a sense, “buying” manuscripts. But, for now at least, I don’t make decisions about the fate of novels, and so I don’t have to go toe-to-toe with agents. Good thing. They scare me. (Looking at you, Lucienne Diver.) I am not the most talented writer I know. Not by a long shot. I am good. I believe that. My character work is strong. My world building is imaginative. My prose is clean and tight and it flows nicely. I write convincing, effective dialogue and I have a fine eye for detail. My plotting and pacing, which were once just okay, have gotten stronger over the years. I think writing the Thieftaker books — being forced to blend my fictional plots with real historical events — forced me to improve, and that improvement has shown up in the narratives of the Islevale and Radiants books.

I am not the most talented writer I know. Not by a long shot. I am good. I believe that. My character work is strong. My world building is imaginative. My prose is clean and tight and it flows nicely. I write convincing, effective dialogue and I have a fine eye for detail. My plotting and pacing, which were once just okay, have gotten stronger over the years. I think writing the Thieftaker books — being forced to blend my fictional plots with real historical events — forced me to improve, and that improvement has shown up in the narratives of the Islevale and Radiants books. As many of you know, I am once again co-editing an anthology for

As many of you know, I am once again co-editing an anthology for  I discussed the Thieftaker books in last week’s post, and I mentioned how my love of U.S. history steered me toward setting the series in pre-Revolutionary Boston. But I failed to mention then that upon deciding to set the books in 1760s Boston, I then had to dive into literally months of research. Sure, I had read colonial era history for my Ph.D. exams, but I had never looked at the period the way I would need to in order to use it as a setting for a novel, much less several novels and more than a dozen pieces of short fiction. Ironically, as a fiction author I needed far more basic factual information about the city, about the time period, about the historical figures who would appear in my narratives, than I ever did as a doctoral candidate.

I discussed the Thieftaker books in last week’s post, and I mentioned how my love of U.S. history steered me toward setting the series in pre-Revolutionary Boston. But I failed to mention then that upon deciding to set the books in 1760s Boston, I then had to dive into literally months of research. Sure, I had read colonial era history for my Ph.D. exams, but I had never looked at the period the way I would need to in order to use it as a setting for a novel, much less several novels and more than a dozen pieces of short fiction. Ironically, as a fiction author I needed far more basic factual information about the city, about the time period, about the historical figures who would appear in my narratives, than I ever did as a doctoral candidate. The same is true of the worlds I build from scratch for my novels. My most recent foray into wholesale world building was the prep work I did for my Islevale Cycle, the time travel/epic fantasy books I wrote a few years ago. As with my Thieftaker research, my world building for the Islevale trilogy consumed months. I began (as I do with my research) with a series of questions about the world, things I knew I had to work out before I could write the books. How did the various magicks work? What were the relationships among the various island nations? Where did my characters fit into these dynamics? Etc.

The same is true of the worlds I build from scratch for my novels. My most recent foray into wholesale world building was the prep work I did for my Islevale Cycle, the time travel/epic fantasy books I wrote a few years ago. As with my Thieftaker research, my world building for the Islevale trilogy consumed months. I began (as I do with my research) with a series of questions about the world, things I knew I had to work out before I could write the books. How did the various magicks work? What were the relationships among the various island nations? Where did my characters fit into these dynamics? Etc.