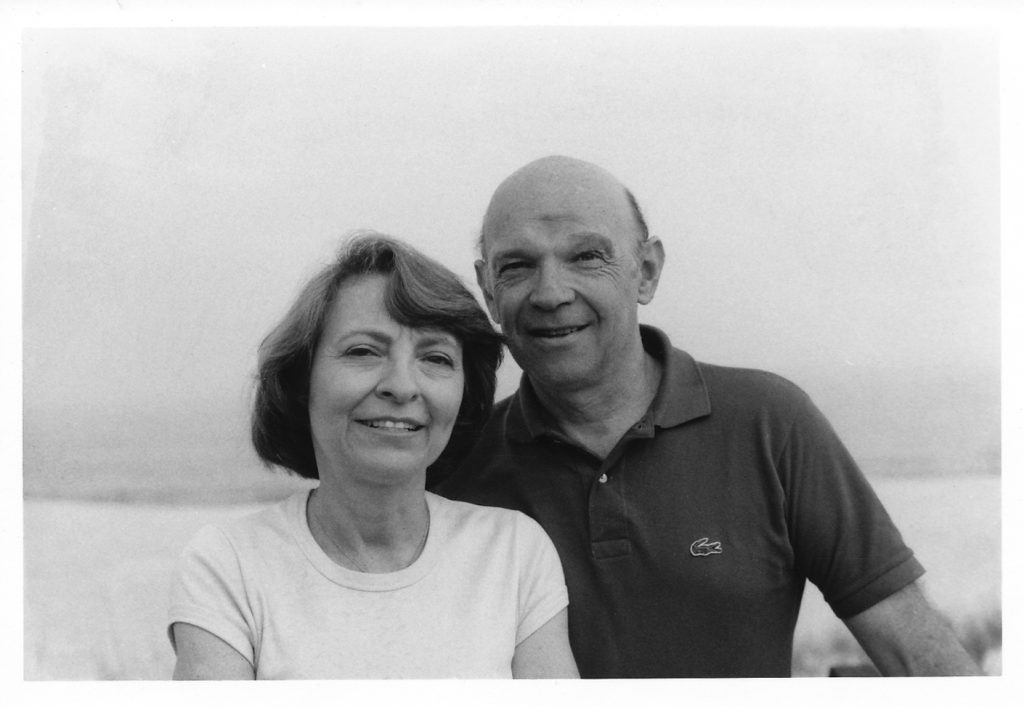

I write about my father a lot in this blog. Last year at this time, I wrote a long tribute to him commemorating what would have been his one hundred and second birthday. I write about my mother as well (her birthday is in February). We lost both of them way too early, and I miss them both more than I can put into words.

I won’t repeat last year’s tribute. If you’re interested, you can find it here. But I did want to share a memory of my dad that I find myself relating to with particular resonance this year.

I grew up the youngest of four children in a privileged family, and all of us enjoyed giving as much as we did receiving. Our Christmas mornings tended to be affairs of largess; we all had enormous gift piles. Record albums, clothes, books, the occasional piece of jewelry — as I say, there was always plenty under our tree. The Christmas morning I’m remembering came when I was in my early-to-mid twenties, and was home visiting either from Providence, where I lived after completing college, or California, where I attended graduate school.

All of us were in our usual frenzy of tearing wrapping paper and oohing and aahing over one another’s gifts. Dad sat watching us all, not unwrapping anything himself, but smiling contentedly. One of us said something to him — probably prompting him to open one of his as-yet-unopened gifts, and he waved off the comment.

“This is my present,” he said. “Watching all of you.”

“This is my present,” he said. “Watching all of you.”

I know: It sounds like a line from a Hallmark holiday movie. Thing is, he meant it. There was nothing he enjoyed more than watching and listening as his kids and his beloved wife talked and laughed.

I remember another time, the last summer we had with him: My mother had died the previous fall, and not long after Dad was diagnosed with leukemia. But during the summer, we rented a house in New England that was huge enough to accommodate all of us — my dad; my brother Bill and his partner, Sandy; my sister, Liz, her husband, and their two young children; my brother Jim, his wife, Karen, and their son (their daughter would come along a year later); and Nancy, Alex, and me (Erin was born three years later).

We had a great week, but there was one night in particular when we put the kids to bed, and dad retired early, leaving my siblings and me and our partners to hang out on our own. We didn’t realize how much sound traveled in the house, but we learned the next morning that Dad had heard us the whole time. He wasn’t at all angry, and he didn’t mind being kept up.

“Listening to you all laughing was better than sleep.”

By that time, of course, I was a father, and was starting to understand what he meant. I didn’t appreciate it fully, though, until after Erin was born.

I have been fortunate to hear live performances by some of the most phenomenal musicians in the world — jazz and classical, blues and bluegrass, rock and country. I have heard remarkable birdsong throughout North America, in New Zealand and Australia, in Costa Rica, in several parts of Europe. I have heard coyotes call in the desert, and Screech Owls trilling on a rainy night in Oregon, and Whip Poor Wills singing on summer nights in Tennessee. There is no sound I have ever heard that compares to the music of my daughters laughing together.

Nancy, the girls, and I have our own Christmases now, of course. There is always plenty under the tree, although this year Nancy and I don’t have much for each other. That’s all right. I won’t miss the presents. Because I’ll be able to sit, as my father did all those years ago, and watch Alex and Erin enjoying their holiday, laughing with each other and with us. That will be my present.

That, and my memories of my dad.

Happy birthday, Pop. Love you.

I did. Exile on Main Street, by the Rolling Stones. A legendary double-album by the rock band of the era. “I think you’re ready for this,” he said.

I did. Exile on Main Street, by the Rolling Stones. A legendary double-album by the rock band of the era. “I think you’re ready for this,” he said. When the girls were little, we used to take them into town, meet up with their friends and their friends’ parents, take a bunch of photos (all of them too cute for words), and then commence the hunt for goodies. We would actually bring a bag or two of candy to supplement what our friends were giving out, so that we wouldn’t be total freeloaders, and while half the parents (sometimes the dads, sometimes the moms) went out walking with the kids, the other half stayed, gave out candy, drank a bit of wine. Those were great evenings. Sadly, I missed out on trick-or-treating as often as I participated. Back then, World Fantasy Convention was held each year on Halloween weekend. If Halloween fell anywhere between a Thursday and a Sunday, chances were I’d be away. Sometimes, if the travel was complicated enough, I missed out on Halloween on other days as well. I considered WFC one of the most important professional events on my calendar — I still do — but looking back, I wish I’d skipped the convention more often than I did. I missed out by not taking my girls door-to-door more than I did.

When the girls were little, we used to take them into town, meet up with their friends and their friends’ parents, take a bunch of photos (all of them too cute for words), and then commence the hunt for goodies. We would actually bring a bag or two of candy to supplement what our friends were giving out, so that we wouldn’t be total freeloaders, and while half the parents (sometimes the dads, sometimes the moms) went out walking with the kids, the other half stayed, gave out candy, drank a bit of wine. Those were great evenings. Sadly, I missed out on trick-or-treating as often as I participated. Back then, World Fantasy Convention was held each year on Halloween weekend. If Halloween fell anywhere between a Thursday and a Sunday, chances were I’d be away. Sometimes, if the travel was complicated enough, I missed out on Halloween on other days as well. I considered WFC one of the most important professional events on my calendar — I still do — but looking back, I wish I’d skipped the convention more often than I did. I missed out by not taking my girls door-to-door more than I did.

From Virginia Beach, I went to Brooklyn, where I spent two evenings with my older daughter. She looks beautiful, seems great, has a ton of energy, and was her normal, playful, thoughtful, intelligent, insightful, slightly acerbic self. Seeing her, having such amazing time with her, was reassuring to say the least.

From Virginia Beach, I went to Brooklyn, where I spent two evenings with my older daughter. She looks beautiful, seems great, has a ton of energy, and was her normal, playful, thoughtful, intelligent, insightful, slightly acerbic self. Seeing her, having such amazing time with her, was reassuring to say the least.

I have to confess that I don’t remember when I first met Wayne McCalla.

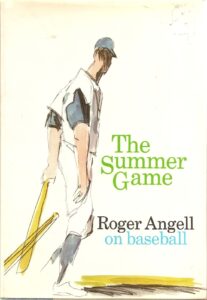

I have to confess that I don’t remember when I first met Wayne McCalla. Beginning in 1962, and continuing through most of the next sixty years, Angell wrote about baseball, contributing articles to The New Yorker a couple of times each season, usually once during spring training, and once at the end of the World Series. Some seasons he added a mid-season essay. His articles were later collected in volumes — The Summer Game (1972), Five Seasons (1977), Late Innings (1982), Season Ticket (1988), and Once More Around the Park (1991). I own all of them, and have read them multiple times.

Beginning in 1962, and continuing through most of the next sixty years, Angell wrote about baseball, contributing articles to The New Yorker a couple of times each season, usually once during spring training, and once at the end of the World Series. Some seasons he added a mid-season essay. His articles were later collected in volumes — The Summer Game (1972), Five Seasons (1977), Late Innings (1982), Season Ticket (1988), and Once More Around the Park (1991). I own all of them, and have read them multiple times. Because eventually I did find The One, and I married her 31 years ago this week. (Our anniversary is Thursday.)

Because eventually I did find The One, and I married her 31 years ago this week. (Our anniversary is Thursday.)