Ideally, every new book and story we write is not just an adventure in imagination, a chance to discover new characters and settings and narratives, but also a learning opportunity. I continue to improve my writing with each project, and I try to do at least one thing new with each story or novel. For instance, while working on my short story for the Dragonesque anthology, which will be published later this year by Zombies Need Brains, I was aware that my editors (and good friends), Joshua Palmatier and S.C. Butler, both tend to cut out a few dialog tags from all the stories they edit. I was determined to make that impossible for them. And I wound up managing to write the entire story using only a single instance of “said” or “asked.” Let them find something else to cut! In doing this, I actually made the story leaner, more concise, and more fun to read.

With this in mind, I thought it might be helpful to list a few things I learned, reminded myself of, and/or tried to do differently while writing my Chalice War trilogy, which debuts on Friday, May 5 (THIS FRIDAY) with the release of The Chalice War: Stone from Bell Bridge Books.

With this in mind, I thought it might be helpful to list a few things I learned, reminded myself of, and/or tried to do differently while writing my Chalice War trilogy, which debuts on Friday, May 5 (THIS FRIDAY) with the release of The Chalice War: Stone from Bell Bridge Books.

Journal about, well, everything: The first book in the Chalice War series includes a frenzied chase/trek across the U.S., and a series of climactic scenes that are set in Las Vegas. The second book is set in Australia — in Sydney, as well as in the tourist town of Kiama along the Illawarra coast. The third book is set in Ireland. I have driven across this country a few times, and I’ve been to all the places I just mentioned. I have driven into Vegas at night, approaching from the east, as my characters do. I have spent time along the Irish coast (although not quite the same part). I have spent a good deal of time in Kiama.

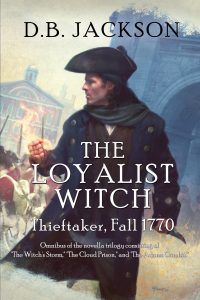

And I have journaled about all of these experiences. While writing descriptive passages for the books, I drew heavily on old journal entries (and also on my old photographs). I’ll admit this is not the first time I have drawn upon personal experiences and writings for this sort of thing. When I wrote the Fearsson books, I consulted journal entries from visits to the Sonoran Desert. Whenever I write in the Thieftaker world, I draw on old entries from my college years in New England. This is not a new lesson, so much as something I was reminded of while writing the Chalice books. But the value of the point is undeniable. The more we write, the better we get, and journaling helps us keep in practice, which is reason enough to do it. But it can also be a terrific source for material that we can adapt to our fiction, be it in the form of descriptive writing, character development, or even plot points.

Dude, lighten up: My books tend to be very serious. Bad things happen all the time to good people. The fate of the world hangs in the balance again and again and again. It’s kind of like Buffy’s tombstone from the finale of the fifth season of Buffy The Vampire Slayer — “She saved the world. A lot.” I’m not suggesting this is a bad thing. People return to my books because I keep the stakes high, and they like that.

And the stakes could not be higher in the Chalice War books. The fate of our world is balanced on a knife’s edge throughout all three volumes. Serious stuff.

But people who know me know that I enjoy laughing and that I joke around a lot. And in these books, really for the first time in my career, I rely heavily on humor. I won’t go so far as to call the books “light-hearted” or “romps” — the series is action-packed, and, as I say, the stakes could not be higher. Still, there is a lot in these pages that made me laugh as I wrote, and I expect the books will make my readers laugh as well. A lot.

Limit the number of POV characters: Early in my career, when I wrote my big, fat epic fantasies (The LonTobyn Chronicle, Winds of the Forelands, Blood of the Southlands), I used a vast array of point of view characters. I was writing big sweeping stories and had a cast to match. I went from those to Thieftaker and Fearsson, which both had, basically, one POV character (the first chapters of the second and third Fearsson books were written in other POVs, but then both books reverted to Jay). Noir-style mysteries, I felt, worked best when told from the perspective of the investigator. Later books (Islevale, Radiants) fell somewhere in between — more than one, but not as many as those huge stories I told early on.

With this newest trilogy, I tried something a little different. I needed more than one POV character, but I wanted to have a maximum of three in each book. And that’s pretty much what I did. Chapter one of books I and II are from different POVs, but after that I have two POV characters in Stone, the first book, and three POV characters in the others.

And I like the way the novels read with limited casts of this sort. There is enough variety in the voices to propel the books forward with each POV shift, but there are few enough narrators that my readers can grow comfortable with the characters and their personalities. Obviously, every story is different, and what works with one series won’t necessarily work with another, but going forward, I will look for opportunities to limit my cast of narrating characters to more manageable numbers.

I hope you will check out the new series. I really do believe you’ll enjoy the books.

In the meantime, keep writing!

I’ve been thinking of this a lot recently because I am in the process — finally! — of reissuing my Winds of the Forelands series, which has been out of print for several years. The books are currently being scanned digitally (they are old enough that I never had digital files of the final — copy edited and proofed — versions of the books) and once that process is done, I will edit and polish them and find some way to put them out into the world again.

I’ve been thinking of this a lot recently because I am in the process — finally! — of reissuing my Winds of the Forelands series, which has been out of print for several years. The books are currently being scanned digitally (they are old enough that I never had digital files of the final — copy edited and proofed — versions of the books) and once that process is done, I will edit and polish them and find some way to put them out into the world again. I feel that way about the second and third books in my Case Files of Justis Fearsson series, His Father’s Eyes and Shadow’s Blade. These books are easily as good as the best Thieftaker books, but the Fearsson series, for whatever reason, never took off the way Thieftaker did. Hence, few people know about the Fearsson books, and it’s a shame, because these two volumes especially include some of the best writing I’ve ever done.

I feel that way about the second and third books in my Case Files of Justis Fearsson series, His Father’s Eyes and Shadow’s Blade. These books are easily as good as the best Thieftaker books, but the Fearsson series, for whatever reason, never took off the way Thieftaker did. Hence, few people know about the Fearsson books, and it’s a shame, because these two volumes especially include some of the best writing I’ve ever done. Same with the Islevale Cycle trilogy. Time’s Children is the best reviewed book I’ve written, and Time’s Demon and Time’s Assassin build on the work I did in that first volume. But the books did poorly commercially because the series got lost in a complete reshuffling of the management and staffing of the company that published the first two installments. The series died before it ever had a chance to succeed. Which is a shame, because the world building I did for Islevale is my best by a country mile, and the plotting is the most ambitious and complex I ever attempted. Those three novels are certainly among my very favorites.

Same with the Islevale Cycle trilogy. Time’s Children is the best reviewed book I’ve written, and Time’s Demon and Time’s Assassin build on the work I did in that first volume. But the books did poorly commercially because the series got lost in a complete reshuffling of the management and staffing of the company that published the first two installments. The series died before it ever had a chance to succeed. Which is a shame, because the world building I did for Islevale is my best by a country mile, and the plotting is the most ambitious and complex I ever attempted. Those three novels are certainly among my very favorites. But of all the novels I have published thus far, my favorite is Invasives, the second Radiants book. As I have mentioned here before, Invasives saved me. This was the book I was writing when our older daughter received her cancer diagnosis. I briefly shelved the project, thinking I couldn’t possible write while in the midst of that crisis. I soon realized, however, that I HAD to write, that writing would keep me centered and sane. I believe pouring all my emotional energy into the book explains why Invasives contains far and away the best character work I have ever done. It’s also paced better than any book I’ve written. It is simply my best.

But of all the novels I have published thus far, my favorite is Invasives, the second Radiants book. As I have mentioned here before, Invasives saved me. This was the book I was writing when our older daughter received her cancer diagnosis. I briefly shelved the project, thinking I couldn’t possible write while in the midst of that crisis. I soon realized, however, that I HAD to write, that writing would keep me centered and sane. I believe pouring all my emotional energy into the book explains why Invasives contains far and away the best character work I have ever done. It’s also paced better than any book I’ve written. It is simply my best. For the past several weeks, I have been sharing “My Best Mistakes,” which have included

For the past several weeks, I have been sharing “My Best Mistakes,” which have included  Very early in my career, when my first book, Children of Amarid, was the only one I had out, I responded publicly to a online review from a less-than-delighted reader. Amazon was still a novelty (no pun intended) as was the notion of online reader reviews. (Hard to imagine, right? That the idea of readers offering reviews of the books they’d read should have been new and different and even a bit odd?) I don’t remember what the reader in question objected to about the book, nor do I remember what I said in my public response. The original book is out of print now — only the 2016 reissues are available on the site, so our exchange is lost to the ages. All I know is that someone criticized the book, I didn’t take the criticism well, and I took it upon myself to write a reply and post it to the Children of Amarid Amazon page.

Very early in my career, when my first book, Children of Amarid, was the only one I had out, I responded publicly to a online review from a less-than-delighted reader. Amazon was still a novelty (no pun intended) as was the notion of online reader reviews. (Hard to imagine, right? That the idea of readers offering reviews of the books they’d read should have been new and different and even a bit odd?) I don’t remember what the reader in question objected to about the book, nor do I remember what I said in my public response. The original book is out of print now — only the 2016 reissues are available on the site, so our exchange is lost to the ages. All I know is that someone criticized the book, I didn’t take the criticism well, and I took it upon myself to write a reply and post it to the Children of Amarid Amazon page. Some years later, soon after the release of Spell Blind, the first book in The Case Files of Justis Fearsson, another Amazon reviewer panned the book because my book was “a blatant rip-off” of Jim Butcher’s Harry Dresden books, “a ludicrous case of copycatting.” For the record, I didn’t copy Dresden at all. I had only read the first two books of the series, and the “copycatting” the reviewer claimed I’d done amounted to using tropes of the genre, not elements of Butcher’s work. And so I responded to the review, wanting to set the record straight.

Some years later, soon after the release of Spell Blind, the first book in The Case Files of Justis Fearsson, another Amazon reviewer panned the book because my book was “a blatant rip-off” of Jim Butcher’s Harry Dresden books, “a ludicrous case of copycatting.” For the record, I didn’t copy Dresden at all. I had only read the first two books of the series, and the “copycatting” the reviewer claimed I’d done amounted to using tropes of the genre, not elements of Butcher’s work. And so I responded to the review, wanting to set the record straight. As you know, early in 2023 I will be coming out with a new urban fantasy series that is steeped in Celtic mythology. Before working on this series, I hadn’t known much about Celtic lore. But I did my research, learned all I could, and then started to imagine ways in which I might blend those Celtic traditions with my vision for the stories I wanted to write. I tried to be respectful of traditions that are not my own, while also having fun and writing something I hoped would be fun for my readers.

As you know, early in 2023 I will be coming out with a new urban fantasy series that is steeped in Celtic mythology. Before working on this series, I hadn’t known much about Celtic lore. But I did my research, learned all I could, and then started to imagine ways in which I might blend those Celtic traditions with my vision for the stories I wanted to write. I tried to be respectful of traditions that are not my own, while also having fun and writing something I hoped would be fun for my readers. Around that same time, I was also reading submissions for the Temporally Deactivated anthology, my first co-editing venture. Last year I opened my freelance editing business, and a year ago at this time, I was editing a manuscript for a client.

Around that same time, I was also reading submissions for the Temporally Deactivated anthology, my first co-editing venture. Last year I opened my freelance editing business, and a year ago at this time, I was editing a manuscript for a client. Last week, I wrote about planning out my professional activities for the coming year. This week, I want to discuss a different element of professional planning. My point in starting off with a list of those projects from past years is that just about every year, I try to take on a new challenge, something I’ve never attempted before. I didn’t start off doing this consciously — I didn’t say to myself, “I’m going to start doing something new each year, just to shake things up.” It just sort of happened.

Last week, I wrote about planning out my professional activities for the coming year. This week, I want to discuss a different element of professional planning. My point in starting off with a list of those projects from past years is that just about every year, I try to take on a new challenge, something I’ve never attempted before. I didn’t start off doing this consciously — I didn’t say to myself, “I’m going to start doing something new each year, just to shake things up.” It just sort of happened. But those new challenges did more than that. They kept my professional routine fresh. I am a creature of habit. I try to write/edit/work every day, so in a general sense, my work days and work weeks don’t change all that much. By varying the content of my job — by writing new kinds of stories and expanding my professional portfolio to include editing as well as writing — I made the routine feel new and shiny and exciting. And at the same time, these new projects made it possible to return to some old favorites, notably the Thieftaker series, with renewed enthusiasm.

But those new challenges did more than that. They kept my professional routine fresh. I am a creature of habit. I try to write/edit/work every day, so in a general sense, my work days and work weeks don’t change all that much. By varying the content of my job — by writing new kinds of stories and expanding my professional portfolio to include editing as well as writing — I made the routine feel new and shiny and exciting. And at the same time, these new projects made it possible to return to some old favorites, notably the Thieftaker series, with renewed enthusiasm.