Nearly two months ago, early in the new year, I posted on social media that I had some exciting professional news I couldn’t share quite yet. I was thrilled, and wanted to let people know. But I also didn’t want to say anything before all the details had been settled. So I posted my little teaser, forgetting the one immutable rule of the publishing business: Things always happen slower than one thinks they will.

Nearly two months ago, early in the new year, I posted on social media that I had some exciting professional news I couldn’t share quite yet. I was thrilled, and wanted to let people know. But I also didn’t want to say anything before all the details had been settled. So I posted my little teaser, forgetting the one immutable rule of the publishing business: Things always happen slower than one thinks they will.

Well, I can finally make the announcement official. I have signed and sent the contracts, and they are (or soon will be) back in the hands of my publisher.

I have signed a contract for a new trilogy with Belle Books.

What kind of trilogy?

I’ll tell you, but first some brief background. (Sue me: I’m a writer, so I always build suspense, and I’m a historian, so I always fill in backstory . . .)

A little more than a decade ago, in the summer of 2011, I found myself with nothing to write. We (my agent and I) had sold the Thieftaker books to Tor, and had turned in the first volume, but was waiting on revision notes. The year before I’d finished my Blood of the Southlands series and had also published the Robin Hood novelization. We were shopping the Justis Fearsson series, but sensed that the first book needed more work. And, frankly, I was not yet in a state of mind to tackle another rewrite on that front.

And so, with nothing else to do, I started something new. When I named the file folder on my computer desktop, I just called it “NewUF” (new urban fantasy). The book remained untitled for a long time.

The scene I first envisioned (not the first scene in the story) centered around a woman who wakes up from a night she can barely remember with a wound she feels but can’t see. She stumbles to the shower, but the pain only increases. At last she finds herself picking at skin that looks normal but feels rough and scarred. And suddenly blood is cascading down her side. She doesn’t know or remember why.

A little weird, right? Ideas come in all shapes and sizes. Some books take form clearly and sequentially. Some introduce themselves piecemeal, like a jigsaw puzzle. I didn’t know what to make of the scene I’d imagined, but working backward from it I filled out the character of this woman, I sculpted her world, which is basically our world with a magical twist, and I built other characters around her.

The result was a contemporary urban fantasy steeped in Celtic mythology: two women, a Sidhe sorcerer and her human conduit, fighting off shapeshifting Fomhoire demons and their allies from the Underrealm, with the fate of the world hanging in the balance.

It sounds grim, and it also sounds a bit like other books we’ve seen before. It’s neither. Yes, there is some serious shit going down throughout the book, but there is also humor and there are lots of unexpected twists in both the magical underpinnings of the story and the narrative itself.

I wrote the book in about three months. And then I set it aside. I had final edits to do on Thieftaker and I needed to get started on Thieves’ Quarry, the second book in that series. I loved this other book I’d written, but I knew it was part of a larger project, and I didn’t know yet what to do with the next books in the sequence.

Thieftaker and its sequel did well. We sold the Fearsson series. And abruptly, I had more than enough work to keep me busy for a few years. But I certainly never forgot about my Celtic series, and a few years later, when I pulled the book out of the proverbial drawer, I reworked it, taking into account my agent’s editorial comments from that first draft, and all that I had learned since while writing the Thieftaker and Fearsson books. A couple of years after that, I took it out again and edited it some more. And finding myself once more with a bit of time, I started work on the second volume.

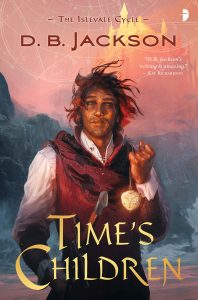

This second book built on what I’d done in book one, but the plot stalled at the 2/3 mark (as books often do) and, with other work to get done — now on the Islevale series — I put it away again.

And on it went. I returned to these books again and again, polishing book one to a high shine, eventually completing and then polishing book two, and finally developing an idea for the third book in the trilogy. By then we’d reached the middle of 2021. I was working on the Radiants series with an incredible publisher and editor, and I decided it was finally time to bring these books out of the drawer they’d been in and present them for possible publication. Which brings us to this post.

We don’t always know what will happen with the stories and books we write. The first book in this new Celtic urban fantasy has, at this point, been through five or six iterations and countless edits. It wasn’t ready in 2011. Not even close. But I believed in the idea, and I knew that with work I could make it into a publishable novel.

Sure, I have other books and stories that have never gone anywhere and probably won’t. I also have ideas like this one that are still awaiting their time.

Never give up on a story you love. Maybe it’s not ready yet. Maybe you haven’t figured out how to end it or where to take subsequent volumes. Maybe you’re not sure what it needs, but you know it needs something. Stick with it. Work on other things as well. Sometimes we need to confront stubborn ideas and stories head on. Sometimes we need to set them aside and let them percolate while we write other characters in other worlds.

I don’t yet know what to call this new series. When I know, you’ll know. The first book is titled Stone Bound. I expect it will be out later in 2022 or early in 2023. The second book is called The Demon Cauldron.

Have a great week.

I am not the most talented writer I know. Not by a long shot. I am good. I believe that. My character work is strong. My world building is imaginative. My prose is clean and tight and it flows nicely. I write convincing, effective dialogue and I have a fine eye for detail. My plotting and pacing, which were once just okay, have gotten stronger over the years. I think writing the Thieftaker books — being forced to blend my fictional plots with real historical events — forced me to improve, and that improvement has shown up in the narratives of the Islevale and Radiants books.

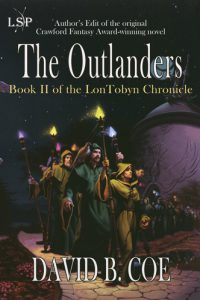

I am not the most talented writer I know. Not by a long shot. I am good. I believe that. My character work is strong. My world building is imaginative. My prose is clean and tight and it flows nicely. I write convincing, effective dialogue and I have a fine eye for detail. My plotting and pacing, which were once just okay, have gotten stronger over the years. I think writing the Thieftaker books — being forced to blend my fictional plots with real historical events — forced me to improve, and that improvement has shown up in the narratives of the Islevale and Radiants books. The Outlanders, my second book, may well be the most significant of all the books I’ve published. I knew I had it in me to write one book. But when I finished The Outlanders, and realized it was even better than CofA, I knew I was more than a guy who could write a novel. I was an author. And when Children of Amarid and The Outlanders together were given the Crawford Fantasy Award by the IAFA (International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts), for best fantasy by a new writer, I knew I would have a professional career beyond that first series.

The Outlanders, my second book, may well be the most significant of all the books I’ve published. I knew I had it in me to write one book. But when I finished The Outlanders, and realized it was even better than CofA, I knew I was more than a guy who could write a novel. I was an author. And when Children of Amarid and The Outlanders together were given the Crawford Fantasy Award by the IAFA (International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts), for best fantasy by a new writer, I knew I would have a professional career beyond that first series. I did just that. I started with some short stories that have never since seen the light of day, but which helped me to shape the contours of my world and its history. Then I began work on the novel, and by September had completed the first five chapters of what would eventually be Children of Amarid, my first published novel. I gave the manuscript to a friend of the family who had been a publisher, and he agreed to act as my agent, operating under standard agenting fees. He sent those five chapters and an outline of the rest of the book to various fantasy publishers.

I did just that. I started with some short stories that have never since seen the light of day, but which helped me to shape the contours of my world and its history. Then I began work on the novel, and by September had completed the first five chapters of what would eventually be Children of Amarid, my first published novel. I gave the manuscript to a friend of the family who had been a publisher, and he agreed to act as my agent, operating under standard agenting fees. He sent those five chapters and an outline of the rest of the book to various fantasy publishers. February has begun, Punxsutawney Phil has done his schtick, and time seems to be moving at breakneck speed. In a little over two weeks, Invasives, the second Radiants book, will be released by Belle Books.

February has begun, Punxsutawney Phil has done his schtick, and time seems to be moving at breakneck speed. In a little over two weeks, Invasives, the second Radiants book, will be released by Belle Books.

The thing is, we writers do and must “write what we know.” But we understand that “what we know” does not equal “what we have lived.” Writing is all about emotion, about delving into the thoughts and feelings and visceral reactions of our point of view characters. I may not have ever traveled through time (for example), or investigated a murder in pre-Revolutionary Boston, or discovered that I possess supernatural powers and then been pursued by rogue government agents intent on killing my family and making me their weapon. (If you haven’t read Radiants, it’s really time you did.) But even if I haven’t done those things, I have lived the gamut of emotions my characters experience. I have known fear. I have been in love. I adore my children and have been frightened for them. I have been enraged. I have experienced physical pain and illness, exhaustion and hunger, desire and pleasure. I have known joy and confusion and shock, the thrill of ambition realized and the bitter disappointment of expectation thwarted. I can go on, but I think you get my point.

The thing is, we writers do and must “write what we know.” But we understand that “what we know” does not equal “what we have lived.” Writing is all about emotion, about delving into the thoughts and feelings and visceral reactions of our point of view characters. I may not have ever traveled through time (for example), or investigated a murder in pre-Revolutionary Boston, or discovered that I possess supernatural powers and then been pursued by rogue government agents intent on killing my family and making me their weapon. (If you haven’t read Radiants, it’s really time you did.) But even if I haven’t done those things, I have lived the gamut of emotions my characters experience. I have known fear. I have been in love. I adore my children and have been frightened for them. I have been enraged. I have experienced physical pain and illness, exhaustion and hunger, desire and pleasure. I have known joy and confusion and shock, the thrill of ambition realized and the bitter disappointment of expectation thwarted. I can go on, but I think you get my point.

This is a topic to which I intend to return next week and in the weeks to come. Because when we start to think of “write what you know” as an invitation to think more about what our lives, despite their mundanity, have in common with the lives of our characters, we find new ways to enrich our storytelling and world building.

This is a topic to which I intend to return next week and in the weeks to come. Because when we start to think of “write what you know” as an invitation to think more about what our lives, despite their mundanity, have in common with the lives of our characters, we find new ways to enrich our storytelling and world building.