Many years back, while I was working on one of the middle books in my Winds of the Forelands quintet, my second series, I came downstairs after a particularly frustrating day of writing and started whining to Nancy about my manuscript. It was terrible, I told her. There was no story there, no way to complete the narrative I’d begun. The book was a disaster, and I might well have to scrap the whole thing.

Many years back, while I was working on one of the middle books in my Winds of the Forelands quintet, my second series, I came downstairs after a particularly frustrating day of writing and started whining to Nancy about my manuscript. It was terrible, I told her. There was no story there, no way to complete the narrative I’d begun. The book was a disaster, and I might well have to scrap the whole thing.

To which she said, mildly, “Ah. You’re at the 60% point?”

The question brought me up short, because that’s exactly where I was. And prompted by her remark, I realized something obvious to her that I’d missed up until then: To that point in my career, every book I’d written had stalled at the 60% mark.

Last week, I began a new “Most Important Lessons” feature that focused on “Dealing With the Slog.” The first post focused on meeting our self-imposed deadlines. Today’s installment will discuss how to address the 60% Stall.

I would love to tell you that as my career has progressed, I have moved past this problem, but I’d be lying. I don’t stall at 60% with every book, but I do run into problems at that point in most manuscripts. It seems to be endemic to my process. And I’m certainly not the only writer who does. The more I talk about the problem, the more I realize it’s fairly common.

The problem as it presents itself to me can be boiled down this way: When I begin a novel, I know what the main conflicts are, and I have a clear understanding of the obstacles I intend to throw in the path of my protagonist(s). And I also have a good sense of how I want my story to end. Quite often, though, as I write my story, certain elements change. I often alter plot points as I write them. My characters assert themselves in subtle ways, developing their own personalities and wills, and forcing me to rethink their arcs.

So those obstacles as I have written them are not quite the same as what I envisioned originally. On the other hand, the ending, as I imagined it, remains largely unchanged. And thus the path between the crisis point for my protagonists and the end point I want them to reach has to change as well. And the pivot point, the moment when we shift from doing all sorts of nasty stuff to our heroes to beginning to have them fight back and turn the tide, usually starts at about the 60% mark. Yes, shit still goes wrong after that. I’m not saying the last third of the novel has to be a golden time for the protagonist. Far from it. But, for me at least, 60% is when things begin to turn.

How do we address the 60% stall?

First, let me tell you what I don’t do. I don’t panic. I don’t rant and rave. I don’t freak out. Not anymore. Not since Nancy pointed out to me that this is something I go through with most of my books. Plot holes happen. The book as we planned it — whether we outline in detail or write by the seat of our pants — doesn’t always look exactly like the book as we write it. And that’s okay. There is still a story here worth telling. There is still a path between where we are at 59% and where we wish to be on the last page. Breathe. Calm down. It’s going to be all right.

The second thing I try to do is assess the deviations between what I’ve written and what I had in mind originally. Quite often, the answer to overcoming the Stall lies in those differences. Maybe (for instance) we have introduced a new character we hadn’t planned on including, and that person’s presence has set up this narrative disconnect. Most likely, that means the character in question needs to figure into the new narrative path leading us from where we are to where we need to be. Or maybe we have added a key plot twist we hadn’t anticipated originally. Again, if that’s the case, chances are our new solution needs to address the consequences of this twist.

The third thing I consider is whether I need to A) change the ending I’d had in mind, B) add an element in the final 40% to deal with the new conditions I’ve created, or C) go back and edit out some of the changes I have allowed to creep into the first 60%. Choice C) is almost always my least favorite option. Why? Because I have written the book as I have thus far for a reason. If I have strayed from my original, pre-writing vision, it’s because new stuff came to me organically, as I wrote. And generally — not always, but most of the time — I find that my organic decisions are my best decisions.

Finally, and most important, I keep writing. I keep moving forward. Even if my (temporary) solution to navigating past the Stall is flawed, I always, ALWAYS believe it is better to keep pushing through. The alternatives are to give up entirely (unthinkable!!) or to retreat into rewrites and try to fix the problem that way, which in my opinion makes the Stall harder to overcome. Every completed manuscript will require editing, and it may well be that after completing the first draft, setting it aside for a while, and then starting the revision process, we will discover solutions to our narrative issues that weren’t obvious when we were in the middle of writing.

The important thing to remember is this: The 60% Stall is not a death knell for our story. It is a temporary setback. It is not cause for panic, but rather for reflection, for brainstorming, for creative thinking about our narrative.

Keep writing!!

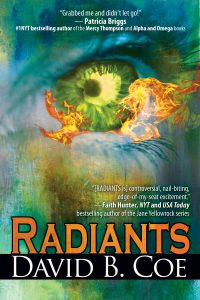

Last week, I was able to share with you the incredible art work for my upcoming novel, Invasives, the second Radiants book, which will be out February 18. And because I’m mentioning the art here, I have yet another excuse to post the image, which I love and will share for even the most contrived of reasons . . .

Last week, I was able to share with you the incredible art work for my upcoming novel, Invasives, the second Radiants book, which will be out February 18. And because I’m mentioning the art here, I have yet another excuse to post the image, which I love and will share for even the most contrived of reasons . . . For the Thieftaker novels, Tor hired the incomparable

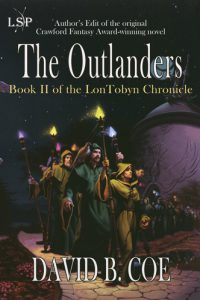

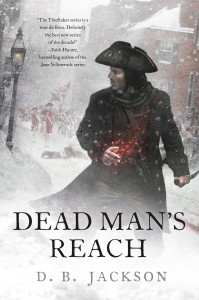

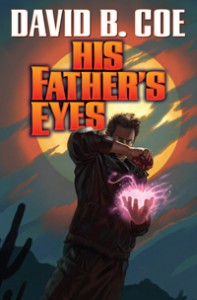

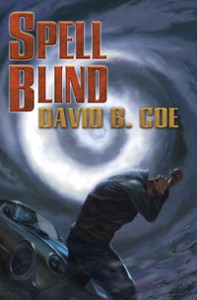

For the Thieftaker novels, Tor hired the incomparable  The thing to remember about artwork, though, is that it’s not enough for the covers to be eye-catching. They also need to tell a story — your story. The Thieftaker covers work because they convey the time period, they offer a suggestion of the mystery contained within, and they hint as well at magic, by always including that swirl of conjuring power in Ethan’s hand. The Islevale covers all have that golden timepiece in them, the chronofor, which enables my Walkers to move through time. All my traditional epic fantasy covers, from the LonTobyn books through the Forelands and Southlands series, convey a medieval fantasy vibe. Readers who see those books, even if they don’t know me or my work, will have an immediate sense of the stories contained within.

The thing to remember about artwork, though, is that it’s not enough for the covers to be eye-catching. They also need to tell a story — your story. The Thieftaker covers work because they convey the time period, they offer a suggestion of the mystery contained within, and they hint as well at magic, by always including that swirl of conjuring power in Ethan’s hand. The Islevale covers all have that golden timepiece in them, the chronofor, which enables my Walkers to move through time. All my traditional epic fantasy covers, from the LonTobyn books through the Forelands and Southlands series, convey a medieval fantasy vibe. Readers who see those books, even if they don’t know me or my work, will have an immediate sense of the stories contained within. And that’s what we want. Sure, part of what makes that Invasives cover work is the simple fact that it’s stunning. The eye, the flames, the lighting in the tunnel. It’s a terrific image. But it also tells you there is a supernatural story within. And while the tunnel “setting” is unusual, the presence of train tracks, wires, electric wiring, and even that loudspeaker in the upper left quadrant of the tunnel, combine to tell you the story takes place in our world (or something very much like it). And for those who have seen the cover of the first book in the series, Radiants, the eye and flames mark this new book as part of the same franchise. That’s effective packaging.

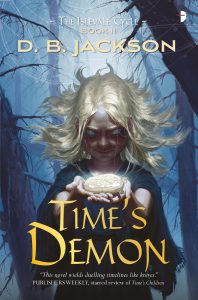

And that’s what we want. Sure, part of what makes that Invasives cover work is the simple fact that it’s stunning. The eye, the flames, the lighting in the tunnel. It’s a terrific image. But it also tells you there is a supernatural story within. And while the tunnel “setting” is unusual, the presence of train tracks, wires, electric wiring, and even that loudspeaker in the upper left quadrant of the tunnel, combine to tell you the story takes place in our world (or something very much like it). And for those who have seen the cover of the first book in the series, Radiants, the eye and flames mark this new book as part of the same franchise. That’s effective packaging. In the same vein, poor marketing practices by a publisher, even if inadvertent, can doom even the most beautiful book. I LOVE the art for Time’s Demon, the second Islevale novel. But the novel came out when the publisher was going through an intense reorganization. It got little or no marketing attention, and despite looking great and being in my view one of the best things I’ve written, it was pretty much the worst-selling book of my career.

In the same vein, poor marketing practices by a publisher, even if inadvertent, can doom even the most beautiful book. I LOVE the art for Time’s Demon, the second Islevale novel. But the novel came out when the publisher was going through an intense reorganization. It got little or no marketing attention, and despite looking great and being in my view one of the best things I’ve written, it was pretty much the worst-selling book of my career. As I mentioned in

As I mentioned in

For the Winds of the Forelands series (Rules of Ascension, Seeds of Betrayal, Bonds of Vengeance, Shapers of Darkness, Weavers of War) , I created what is without a doubt the most complex “calendar” I’ve ever undertaken for any project. For those of you not familiar with the world, I’ll give a very brief description. The world has two moons, Ilias and Panya, the Lovers, who chase each other across the sky. Each turn (month) has one night when both moons are full (the Night of Two Moons) and one night when both moons are dark (Pitch Night). Each turn is also named for a god or goddess, and so each Night of Two Moons and each Pitch Night has a special meaning.

For the Winds of the Forelands series (Rules of Ascension, Seeds of Betrayal, Bonds of Vengeance, Shapers of Darkness, Weavers of War) , I created what is without a doubt the most complex “calendar” I’ve ever undertaken for any project. For those of you not familiar with the world, I’ll give a very brief description. The world has two moons, Ilias and Panya, the Lovers, who chase each other across the sky. Each turn (month) has one night when both moons are full (the Night of Two Moons) and one night when both moons are dark (Pitch Night). Each turn is also named for a god or goddess, and so each Night of Two Moons and each Pitch Night has a special meaning. I did something similar for the Islevale Cycle novels (Time’s Children, Time’s Demon, Time’s Assassin). In this world there are two primary deities, Kheraya (female) and Sipar (male), and the calendar is structured around them. It begins with the spring equinox — Kheraya’s Emergence, a day and night of enhanced magickal power and sensuality. The spring months are known as Kheraya’s Stirring, Kheraya’s Waking, Kheraya’s Ascent. The summer solstice is called Kheraya Ascendent, a day of feasts, celebration, and gift-giving. This is followed by the hot months of summer: Kheraya’s Descent, Fading, and Settling.

I did something similar for the Islevale Cycle novels (Time’s Children, Time’s Demon, Time’s Assassin). In this world there are two primary deities, Kheraya (female) and Sipar (male), and the calendar is structured around them. It begins with the spring equinox — Kheraya’s Emergence, a day and night of enhanced magickal power and sensuality. The spring months are known as Kheraya’s Stirring, Kheraya’s Waking, Kheraya’s Ascent. The summer solstice is called Kheraya Ascendent, a day of feasts, celebration, and gift-giving. This is followed by the hot months of summer: Kheraya’s Descent, Fading, and Settling. The second book, in contrast, was very much a product of its time, and I mean that in a couple of ways. In that book, The Outlanders, my heroes, Jaryd and Alayna are building a life together and starting a family, just as Nancy and I were starting our own family. When writing in book III, Eagle-Sage, about their young daughter, I drew extensively on our experience raising our first child. And in book II, when Niall lost his wife to cancer, I drew upon the experience of watching my father deal with my mother’s death.

The second book, in contrast, was very much a product of its time, and I mean that in a couple of ways. In that book, The Outlanders, my heroes, Jaryd and Alayna are building a life together and starting a family, just as Nancy and I were starting our own family. When writing in book III, Eagle-Sage, about their young daughter, I drew extensively on our experience raising our first child. And in book II, when Niall lost his wife to cancer, I drew upon the experience of watching my father deal with my mother’s death. Still, I can say this: It’s easy to grow attached to one particular franchise, one particularly world and set of characters and style of story. Certainly I have written a good deal in the Thieftaker world, and will soon be coming out with new work about Ethan Kaille, Sephira Pryce, et al. The fact is, though, each time I have moved on to a new project, I have tried (admittedly with varying degrees of success) to challenge myself, to force myself to grow.

Still, I can say this: It’s easy to grow attached to one particular franchise, one particularly world and set of characters and style of story. Certainly I have written a good deal in the Thieftaker world, and will soon be coming out with new work about Ethan Kaille, Sephira Pryce, et al. The fact is, though, each time I have moved on to a new project, I have tried (admittedly with varying degrees of success) to challenge myself, to force myself to grow. After the LonTobyn books, I moved to Winds of the Forelands and Blood of the Southlands, which demanded far more sophisticated world building and character work. After those, I turned to Thieftaker, adding historical and mystery elements to my storytelling and limiting my point of view to a single character. I also started working on the Justis Fearsson books, which explored mental health issues and were my first forays into writing in a contemporary setting. Then I took on the Islevale books, time travel/epic fantasies that presented the most difficult plotting issues I’ve ever faced.

After the LonTobyn books, I moved to Winds of the Forelands and Blood of the Southlands, which demanded far more sophisticated world building and character work. After those, I turned to Thieftaker, adding historical and mystery elements to my storytelling and limiting my point of view to a single character. I also started working on the Justis Fearsson books, which explored mental health issues and were my first forays into writing in a contemporary setting. Then I took on the Islevale books, time travel/epic fantasies that presented the most difficult plotting issues I’ve ever faced. Let’s start with what I mean when I speak of multiple point of view characters. This is NOT an invitation to jump willy-nilly from character to character, sharing their thoughts, emotions, and sensations. That is called head-hopping, and it is considered poor writing. Rather, writing with multiple point of view characters means telling the story with several different narrators, each given her or his own chapters or chapter-sections in which to “tell” their part of the story. When we are in a given character’s point of view, we are privy only to her thoughts and emotions. In the next chapter, we might be privy to the thoughts of someone else in the story. This is an approach used to great effect by George R.R. Martin in his Song of Ice and Fire series. Martin goes so far as to use his chapter headings to tell us who the point of view character is for that section of the story. Guy Gavriel Kay uses multiple point of view quite a bit – in Tigana, in his Fionavar Tapestry, in many of his more recent sweeping historical fantasies. I have used it in my epic fantasy series – The LonTobyn Chronicle, Winds of the Forelands, Blood of the Southlands, The Islevale Cycle.

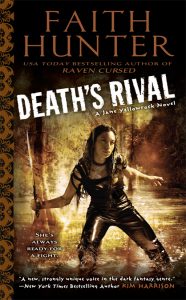

Let’s start with what I mean when I speak of multiple point of view characters. This is NOT an invitation to jump willy-nilly from character to character, sharing their thoughts, emotions, and sensations. That is called head-hopping, and it is considered poor writing. Rather, writing with multiple point of view characters means telling the story with several different narrators, each given her or his own chapters or chapter-sections in which to “tell” their part of the story. When we are in a given character’s point of view, we are privy only to her thoughts and emotions. In the next chapter, we might be privy to the thoughts of someone else in the story. This is an approach used to great effect by George R.R. Martin in his Song of Ice and Fire series. Martin goes so far as to use his chapter headings to tell us who the point of view character is for that section of the story. Guy Gavriel Kay uses multiple point of view quite a bit – in Tigana, in his Fionavar Tapestry, in many of his more recent sweeping historical fantasies. I have used it in my epic fantasy series – The LonTobyn Chronicle, Winds of the Forelands, Blood of the Southlands, The Islevale Cycle. This is in contrast with single character point of view, in which we have only one point of view character for the entire story (and that point of view can be either first or third person). Think of Haith’s Yane Jellowrock series, or my Thieftaker or Justis Fearsson series, or Jim Butcher’s Harry Dresden books, or Suzanne Collins Hunger Games series, or even (for the most part) J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books.

This is in contrast with single character point of view, in which we have only one point of view character for the entire story (and that point of view can be either first or third person). Think of Haith’s Yane Jellowrock series, or my Thieftaker or Justis Fearsson series, or Jim Butcher’s Harry Dresden books, or Suzanne Collins Hunger Games series, or even (for the most part) J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books. For single character point of view we have essentially two kinds of books: urban fantasies that have a mystery element, and YA novels that concentrate as much on the lead character’s emotional development as on external factors. Single character POV tends to be intimate. Readers form a powerful attachment to the narrators of these books. And, of even greater importance, readers learn things about the narrative at the same time the characters do. Even in books that begin with our narrator looking back on past events, we are soon taken back in time so that this older narrative has a sense of immediacy. This is why single character POV works so well in mysteries. The reader gets information as the “detective” does. Discovery happens in real time, as it were.

For single character point of view we have essentially two kinds of books: urban fantasies that have a mystery element, and YA novels that concentrate as much on the lead character’s emotional development as on external factors. Single character POV tends to be intimate. Readers form a powerful attachment to the narrators of these books. And, of even greater importance, readers learn things about the narrative at the same time the characters do. Even in books that begin with our narrator looking back on past events, we are soon taken back in time so that this older narrative has a sense of immediacy. This is why single character POV works so well in mysteries. The reader gets information as the “detective” does. Discovery happens in real time, as it were.