After attending DragonCon and speaking on panels about various aspects of writing, I have found myself thinking—yet again—about the age-old debate between those who outline their books and those who don’t. Or, between planners and pantsers, in the parlance of the discussion. And yes, I know those who write without an outline object to the term “pantsing.” (For those unfamiliar with the term, it comes from the phrase “Flying [or in this case ‘writing’] by the seat of one’s pants.”)

I actually understand and sympathize with these objections to the term. As one who sometimes writes with an outline and sometimes without, I can say with confidence that I am no less a writer when in the midst of those projects that defy my efforts to outline ahead of time.

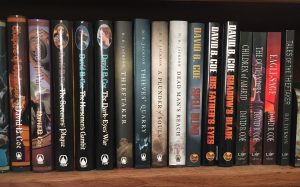

As I have said before, my creative process reinvents itself with each project I take on, often with each book. Some projects lend themselves to outlining and are better suited to a systematic approach to plotting. The Thieftaker books in particular are easy to outline. Indeed, when writing in the Thieftaker universe I feel outlining is absolutely essential. With each book and story, I seek to blend historical events with fictional ones, and keeping the two timelines—the imagined and the real—in sync, demands that I have plan things out with care.

On the other hand, I have written books that I could not outline at all, despite making every attempt to do so. Most notably, the three volumes of my Islevale Cycle (Time’s Children, Time’s Demon, and Time’s Assassin) simply would not submit themselves to any sort of advanced planning. They were like children, refusing to sit still long enough to be photographed.

I have also said before that to me the outlining thing is not so much a binary choice—outline in detail or write the books without any planning at all—as it is a continuum. Even the most dedicated “pantsers” I know have a good idea of where their books are headed. They just don’t like to be tied to a formal outline. In the same way, the most diligent outliners I know leave a great many details out of their outlines, allowing themselves to create in the moment, to preserve the energy that comes from writing organically. Each of us is a little bit planner, a little bit pantser, a little bit country, a little bit rock ‘n roll . . . .

(That is my first, and will be my only, Osmond reference EVER in this blog . . . .)

So why am I revisiting the outlining question this week? Because I am in the process of finishing the third volume in my upcoming Celtic urban fantasy series (which STILL needs a series name!!) and in the final weeks of writing the book, I have been outlining—perhaps it’s more accurate to say RE-outlining—the last ten chapters or so of the story.

And I’ve realized this is something I do a lot. Yes, I try to outline most books, but I almost never outline all the way to the end of the novel. Why? Because things change along the way. I can set out plot points for the first fifteen or twenty chapters of a book before I begin writing Chapter 1, but I know my story is going to shift along the way. Characters will do things that surprise me, that upset my best-laid plans. It’s inevitable. And, in fact, I welcome those kinds of narrative disruptions. When my characters start surprising me, it means they have become fully realized personalities in my head, which is always a good thing.

So, I might outline twenty chapters initially, but I almost always need to adjust my outlines starting at around chapter ten. And then I need to do it again at around chapter seventeen or eighteen. And then I need to do it yet again for the final five or ten chapters of the book.

Put another way, outlining is not simply a task I complete early on, before I start to write my book, and I never think of my outline as a static document. Rather outlining is a process, something I have to revisit several times along the way in order to keep up with the constant creative evolution of my narrative vision.

Because, like so many writers, I am a hybrid. I plan my stories and I also write organically. I adhere to an overarching concept and I adapt to an ever-changing plot line. I take comfort in having a roadmap for my novel and I draw energy from all the story ideas I discover along the way. As I say, my process changes with each project, but these things remain the same.

I like to say there is no single right way to do any of this. Don’t let anyone tell you that you have to plot or you have to write organically. Find the balance that fits best with your creative style.

And, of course, keep writing.

I would love to be a bestselling author. And with each new project I take on, I wonder if this might finally be the literary vehicle that gets me there. Thieftaker, Fearsson, the time travel books, the Radiants franchise. I had high hopes for all of them. All of them were critical successes. None of them has taken me to that next level commercially. So does that mean I should give up?

I would love to be a bestselling author. And with each new project I take on, I wonder if this might finally be the literary vehicle that gets me there. Thieftaker, Fearsson, the time travel books, the Radiants franchise. I had high hopes for all of them. All of them were critical successes. None of them has taken me to that next level commercially. So does that mean I should give up? The difference between what I did with those two projects and what I am telling you not to do is this: I kept working on these books, but I also moved ahead with other projects, so that I wouldn’t stall my career. Yes, I worked for six years on the first Fearsson book. But in that time, I also wrote the Thieftaker books and the Robin Hood novelization. This, by the way, is also the secret to finding that balance I mentioned. By all means, keep working on the one idea, but do so while simultaneously developing others. Don’t become so obsessed with the one challenge that you lose sight of all else.

The difference between what I did with those two projects and what I am telling you not to do is this: I kept working on these books, but I also moved ahead with other projects, so that I wouldn’t stall my career. Yes, I worked for six years on the first Fearsson book. But in that time, I also wrote the Thieftaker books and the Robin Hood novelization. This, by the way, is also the secret to finding that balance I mentioned. By all means, keep working on the one idea, but do so while simultaneously developing others. Don’t become so obsessed with the one challenge that you lose sight of all else. But at the very least, we need to see our main heroes grappling with what they have endured and setting their sights on what is next for them. We don’t need this for every character but we need it for the key ones. Ask yourself, “whose book is this?” For me, this is sometimes quite clear. With the Thieftaker books, every story is Ethan’s. And so I let my readers see Ethan settling back into life with Kannice and making a new, fragile peace with Sephira, or something like that. With other projects, though, “Whose book is this?” can be more complicated. In the Islevale books — my time travel/epic fantasy trilogy — I needed to tie off the loose ends of several plot threads: Tobias and Mara, Droë, and a few others. Each had their “Louis” moment at the end of the last book, and also some sense of closure at the ends of the first two volumes.

But at the very least, we need to see our main heroes grappling with what they have endured and setting their sights on what is next for them. We don’t need this for every character but we need it for the key ones. Ask yourself, “whose book is this?” For me, this is sometimes quite clear. With the Thieftaker books, every story is Ethan’s. And so I let my readers see Ethan settling back into life with Kannice and making a new, fragile peace with Sephira, or something like that. With other projects, though, “Whose book is this?” can be more complicated. In the Islevale books — my time travel/epic fantasy trilogy — I needed to tie off the loose ends of several plot threads: Tobias and Mara, Droë, and a few others. Each had their “Louis” moment at the end of the last book, and also some sense of closure at the ends of the first two volumes. Why do I do this? Why am I suggesting you do it, too? Because while we are telling stories, our books are about more than plot, more than action and intrigue and suspense. Our books are about people. Not humans, necessarily, but people certainly. If we do our jobs as writers, our readers will be absorbed by our narratives, but more importantly, they will become attached to our characters. And they will want to see more than just the big moment when those characters prevail (or not). They will want to see a bit of what comes after.

Why do I do this? Why am I suggesting you do it, too? Because while we are telling stories, our books are about more than plot, more than action and intrigue and suspense. Our books are about people. Not humans, necessarily, but people certainly. If we do our jobs as writers, our readers will be absorbed by our narratives, but more importantly, they will become attached to our characters. And they will want to see more than just the big moment when those characters prevail (or not). They will want to see a bit of what comes after. Nearly two months ago, early in the new year, I posted on social media that I had some exciting professional news I couldn’t share quite yet. I was thrilled, and wanted to let people know. But I also didn’t want to say anything before all the details had been settled. So I posted my little teaser, forgetting the one immutable rule of the publishing business: Things always happen slower than one thinks they will.

Nearly two months ago, early in the new year, I posted on social media that I had some exciting professional news I couldn’t share quite yet. I was thrilled, and wanted to let people know. But I also didn’t want to say anything before all the details had been settled. So I posted my little teaser, forgetting the one immutable rule of the publishing business: Things always happen slower than one thinks they will. I am not the most talented writer I know. Not by a long shot. I am good. I believe that. My character work is strong. My world building is imaginative. My prose is clean and tight and it flows nicely. I write convincing, effective dialogue and I have a fine eye for detail. My plotting and pacing, which were once just okay, have gotten stronger over the years. I think writing the Thieftaker books — being forced to blend my fictional plots with real historical events — forced me to improve, and that improvement has shown up in the narratives of the Islevale and Radiants books.

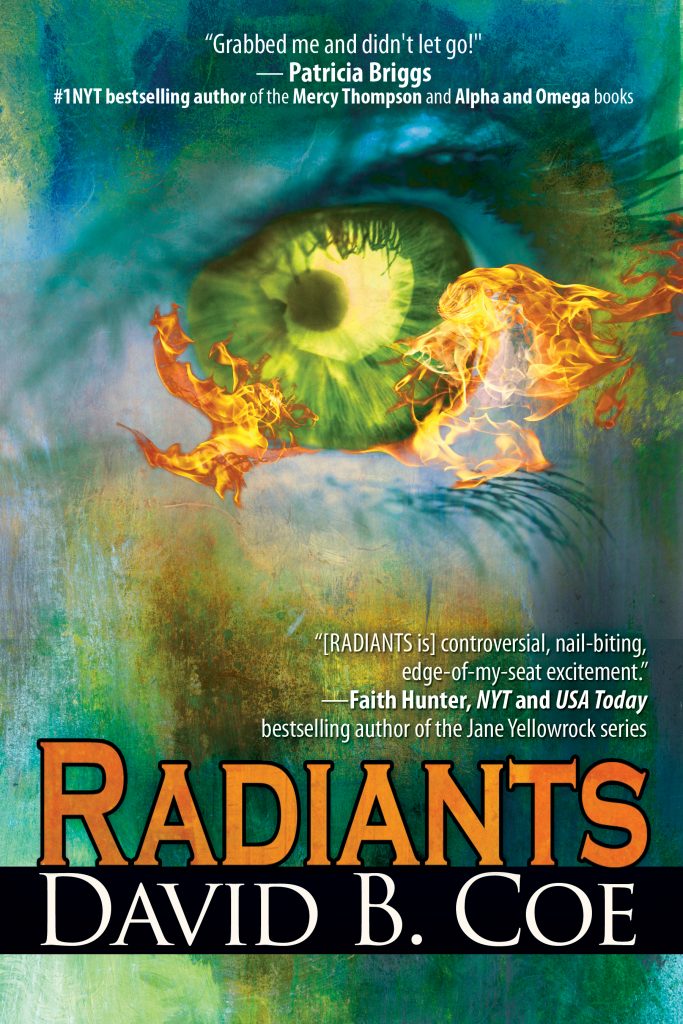

I am not the most talented writer I know. Not by a long shot. I am good. I believe that. My character work is strong. My world building is imaginative. My prose is clean and tight and it flows nicely. I write convincing, effective dialogue and I have a fine eye for detail. My plotting and pacing, which were once just okay, have gotten stronger over the years. I think writing the Thieftaker books — being forced to blend my fictional plots with real historical events — forced me to improve, and that improvement has shown up in the narratives of the Islevale and Radiants books. Last week, I was able to share with you the incredible art work for my upcoming novel, Invasives, the second Radiants book, which will be out February 18. And because I’m mentioning the art here, I have yet another excuse to post the image, which I love and will share for even the most contrived of reasons . . .

Last week, I was able to share with you the incredible art work for my upcoming novel, Invasives, the second Radiants book, which will be out February 18. And because I’m mentioning the art here, I have yet another excuse to post the image, which I love and will share for even the most contrived of reasons . . . For the Thieftaker novels, Tor hired the incomparable

For the Thieftaker novels, Tor hired the incomparable  And that’s what we want. Sure, part of what makes that Invasives cover work is the simple fact that it’s stunning. The eye, the flames, the lighting in the tunnel. It’s a terrific image. But it also tells you there is a supernatural story within. And while the tunnel “setting” is unusual, the presence of train tracks, wires, electric wiring, and even that loudspeaker in the upper left quadrant of the tunnel, combine to tell you the story takes place in our world (or something very much like it). And for those who have seen the cover of the first book in the series, Radiants, the eye and flames mark this new book as part of the same franchise. That’s effective packaging.

And that’s what we want. Sure, part of what makes that Invasives cover work is the simple fact that it’s stunning. The eye, the flames, the lighting in the tunnel. It’s a terrific image. But it also tells you there is a supernatural story within. And while the tunnel “setting” is unusual, the presence of train tracks, wires, electric wiring, and even that loudspeaker in the upper left quadrant of the tunnel, combine to tell you the story takes place in our world (or something very much like it). And for those who have seen the cover of the first book in the series, Radiants, the eye and flames mark this new book as part of the same franchise. That’s effective packaging. I discussed the Thieftaker books in last week’s post, and I mentioned how my love of U.S. history steered me toward setting the series in pre-Revolutionary Boston. But I failed to mention then that upon deciding to set the books in 1760s Boston, I then had to dive into literally months of research. Sure, I had read colonial era history for my Ph.D. exams, but I had never looked at the period the way I would need to in order to use it as a setting for a novel, much less several novels and more than a dozen pieces of short fiction. Ironically, as a fiction author I needed far more basic factual information about the city, about the time period, about the historical figures who would appear in my narratives, than I ever did as a doctoral candidate.

I discussed the Thieftaker books in last week’s post, and I mentioned how my love of U.S. history steered me toward setting the series in pre-Revolutionary Boston. But I failed to mention then that upon deciding to set the books in 1760s Boston, I then had to dive into literally months of research. Sure, I had read colonial era history for my Ph.D. exams, but I had never looked at the period the way I would need to in order to use it as a setting for a novel, much less several novels and more than a dozen pieces of short fiction. Ironically, as a fiction author I needed far more basic factual information about the city, about the time period, about the historical figures who would appear in my narratives, than I ever did as a doctoral candidate. A couple of years ago, I put the finishing touches on the third book of a time travel/epic fantasy trilogy called the

A couple of years ago, I put the finishing touches on the third book of a time travel/epic fantasy trilogy called the  And that next book turned out to be Radiants.

And that next book turned out to be Radiants. As I mentioned in

As I mentioned in