Thirty-three years ago, on Memorial Day Weekend in 1991, Nancy and I were married. We were living in California at the time, doing our graduate work at Stanford, which is where we met. We had a wonderful weekend, which included not just the wedding itself — in the Rodin Sculpture Garden in front of the Stanford Art Museum (now called the Cantor Arts Center) — and our reception at a restaurant called the Velvet Turtle, but also a Saturday softball game for all our guests, and several really nice lunches and dinners. To this day, I don’t know that I have ever felt more loved than I (we) did that weekend. It was glorious.

We had lived together for two years before our wedding, and we were both in our late twenties. We had known almost from the day we started dating that we would spend the rest of our lives together, and by the time that weekend rolled around, we felt ready for the responsibilities and challenges of marriage. And we were. And still, we had no idea.

We had lived together for two years before our wedding, and we were both in our late twenties. We had known almost from the day we started dating that we would spend the rest of our lives together, and by the time that weekend rolled around, we felt ready for the responsibilities and challenges of marriage. And we were. And still, we had no idea.

Life events come in flurries. I remember that year, ours was just one of many weddings we attended. Suddenly, it seemed like everyone we knew was getting married. A few years later, a bunch of our friends started having kids, and pretty soon we ourselves were shopping for a crib and changing table. Skip ahead to today, and we seem to be in a new phase in which many of our friends’ kids and (at least on my side of the family) several relatives are getting married. We have already been to one wedding this year, and we have three more to attend between now and summer’s end. Which is great. The first wedding weekend was loads of fun and I have every reason to expect the others will be as well.

I have no doubt that all four couples feel ready to make their commitment. They understand that marriage brings responsibilities and challenges. And they have no idea.

By any measure, Nancy and I have had a successful marriage. We’ve stayed together through tough times. We have remained true to each other. We are best friends and we are also still very much in love. We have raised two brilliant, reasonably happy, independent, beautiful children. We have pursued careers that we love, and each of us has enjoyed a good deal of success. We have supported each other through disappointments and setbacks, losses and tragedies. And we have shared countless marvelous experiences, things that we both will remember for the rest of our lives.

We have no cause for complaint.

And yet, with all of that going for us, I can also state without any doubt that we have both been through times of deep frustration with each other and with the circumstances of our life together. We have fought. We have gotten fed up. We have weathered periods of difficulty that could have torn us apart.

Some time back — more than ten years now — a couple with whom we spent a good deal of our social time told us they were splitting up. We were utterly gobsmacked. These were people we saw socially on a weekly basis. We celebrated holidays and birthdays with them. They were our closest friends here in our little town. Yet, we’d had no idea that they were having troubles. And I think that reveals something fundamental about the work involved in keeping a marriage going. So much of the effort takes place out of sight, unseen by anyone other than our partner. We don’t want our kids to see it. We don’t want to put on awkward displays in front of our colleagues or friends or families. We do the work in private, make our sacrifices without anyone other than our spouse knowing.

The clichés are true. Of course marriage is about love, about passion, and — even more — about friendship. But it is also about compromise, about joining two lives and finding the balance necessary to make certain that each of those lives feels complete and fulfilling, even as together we build a third life that belongs to both of us. It is a complicated undertaking. And while love and passion are great, there are times when they feel elusive. The kids are sick and you both have work deadlines and the shopping needs to get done. Or one job is more demanding than usual and it’s all you both can do just to get one kid to soccer practice and the other to ballet while also taking care of dinner and arranging the babysitter for the Friday event in town. Work, balance, compromise, sacrifice — sometimes, it feels like that’s all there is. Those early days of the romance, when everything was laughter and love and sex and adventure, seem so very, very distant.

The clichés are true. Of course marriage is about love, about passion, and — even more — about friendship. But it is also about compromise, about joining two lives and finding the balance necessary to make certain that each of those lives feels complete and fulfilling, even as together we build a third life that belongs to both of us. It is a complicated undertaking. And while love and passion are great, there are times when they feel elusive. The kids are sick and you both have work deadlines and the shopping needs to get done. Or one job is more demanding than usual and it’s all you both can do just to get one kid to soccer practice and the other to ballet while also taking care of dinner and arranging the babysitter for the Friday event in town. Work, balance, compromise, sacrifice — sometimes, it feels like that’s all there is. Those early days of the romance, when everything was laughter and love and sex and adventure, seem so very, very distant.

And yet those golden elements of marriage do come around again, if we’re patient, and if we keep making the effort.

So, what advice would I offer to those who are marrying now?

1. Remember to laugh and play. Nancy and I laugh and joke all the time, and we have managed to do this through almost every phase of our marriage. Our shared sense of humor is probably the single most important element of our partnership.

2. Have faith. I’m not talking about religious faith here (though if that’s your thing, great). I mean faith in each other and in what you share. That belief in the fundamental power of our bond has gotten us past some really hard times. The love might not always be palpable, but we KNOW it’s there, and that certainty gets us through.

2. Have faith. I’m not talking about religious faith here (though if that’s your thing, great). I mean faith in each other and in what you share. That belief in the fundamental power of our bond has gotten us past some really hard times. The love might not always be palpable, but we KNOW it’s there, and that certainty gets us through.

3. Honor the work. I believe people cheat because when things grow difficult, they convince themselves that being with someone else will bring back all the fun of the early days without any of the problems. That’s folly. Every relationship takes work. Every relationship goes through rough patches. The work we do builds on itself. Nancy and my marriage is stronger now for all that we’ve put into it over thirty-three years. Why on earth would I want to start over when my best friend and the love of my life is right here?

I wish you love and laughter. Have a great week.

It has now been nearly five months since we lost Alex. I still get the same question — and to be clear, I don’t mind being asked. Not at all. It’s just that I still don’t know how to answer. My friends tell me that five months is nothing, that there is no reason I should have a handle on my emotions already. My therapist says the same. I suppose I should listen to all of them. But I grow impatient with myself. I make my living with words and with emotions. The core of my art is conveying the emotional state of my point of view characters. It’s practically the definition of what a fiction writer does.

It has now been nearly five months since we lost Alex. I still get the same question — and to be clear, I don’t mind being asked. Not at all. It’s just that I still don’t know how to answer. My friends tell me that five months is nothing, that there is no reason I should have a handle on my emotions already. My therapist says the same. I suppose I should listen to all of them. But I grow impatient with myself. I make my living with words and with emotions. The core of my art is conveying the emotional state of my point of view characters. It’s practically the definition of what a fiction writer does. My mother would be 102 years old today, which speaks to a) how very old I am, and b) how uncommonly old she was when she and my father had me. I was born at the end of the Baby Boom, when most couples in their early-forties were done having children. Mom always worried that she would be too old to be a good mother to me, whatever that might have meant. She shouldn’t have worried. She was a wonderful mother — caring, involved, just intrusive enough to make me feel loved without being so intrusive that I felt smothered.

My mother would be 102 years old today, which speaks to a) how very old I am, and b) how uncommonly old she was when she and my father had me. I was born at the end of the Baby Boom, when most couples in their early-forties were done having children. Mom always worried that she would be too old to be a good mother to me, whatever that might have meant. She shouldn’t have worried. She was a wonderful mother — caring, involved, just intrusive enough to make me feel loved without being so intrusive that I felt smothered. Within moments, I was gliding over lush rain forest, surrounded by a ghostly mist, utterly alone, and, it seemed, in a cocoon of sensation — birds called from the green below me, the air was redolent with the sweet scents of rain and earth and forest decay, mist cooled my face, the green of the damp foliage was so brilliant as to appear unreal. Time fell away. Yes, I was moving. But to this day, I couldn’t tell you how long it took me to float through that segment of the course. It could have been mere seconds. It could have been hours. It didn’t matter. For the purposes of that experience, time meant nothing to me. I had escaped the tyranny of clocks and calendars.

Within moments, I was gliding over lush rain forest, surrounded by a ghostly mist, utterly alone, and, it seemed, in a cocoon of sensation — birds called from the green below me, the air was redolent with the sweet scents of rain and earth and forest decay, mist cooled my face, the green of the damp foliage was so brilliant as to appear unreal. Time fell away. Yes, I was moving. But to this day, I couldn’t tell you how long it took me to float through that segment of the course. It could have been mere seconds. It could have been hours. It didn’t matter. For the purposes of that experience, time meant nothing to me. I had escaped the tyranny of clocks and calendars. Today is the 22nd of January. It’s been exactly three months since our older daughter passed away.

Today is the 22nd of January. It’s been exactly three months since our older daughter passed away. As I say, if you know me, you probably don’t find this surprising. I have spoken and written about my love of the Grateful Dead, my experiences shivering outside on cold nights, in the dark of Providence, Rhode Island winters, waiting at the Providence Civic Center for Dead tickets to go on sale. People don’t do that unless they have already done damage to their prefrontal cortex. I could tell additional stories. It is possible that I (and select others) was (were) high during at least one musical performance that we gave while in college. I might remember playing Cat Stevens’s hit “Wild World” and literally watching my digital dexterity degrade over the course of the song.

As I say, if you know me, you probably don’t find this surprising. I have spoken and written about my love of the Grateful Dead, my experiences shivering outside on cold nights, in the dark of Providence, Rhode Island winters, waiting at the Providence Civic Center for Dead tickets to go on sale. People don’t do that unless they have already done damage to their prefrontal cortex. I could tell additional stories. It is possible that I (and select others) was (were) high during at least one musical performance that we gave while in college. I might remember playing Cat Stevens’s hit “Wild World” and literally watching my digital dexterity degrade over the course of the song. At this point, the celebrations of her life are over. Guests from out of town have left. Erin has gone back home. Nancy is starting to work again, and I am gearing up to do the same. We are, I suppose, stepping back into “normal” life. Except there is nothing normal about it, and in ways that truly matter, in ways that will remain with us for the rest of our lives, it will never really be normal at all, ever again.

At this point, the celebrations of her life are over. Guests from out of town have left. Erin has gone back home. Nancy is starting to work again, and I am gearing up to do the same. We are, I suppose, stepping back into “normal” life. Except there is nothing normal about it, and in ways that truly matter, in ways that will remain with us for the rest of our lives, it will never really be normal at all, ever again. The numbness, though — that bothers me. I want to feel. I want to weep for my child or laugh at a golden memory. I want to feel pain and love and loss and connection, because those keep my vision of Alex fresh and present. Numbness threatens oblivion. Numbness makes the loss seem complete, irretrievable — and that I don’t want. Not ever. Better to cry every day for the rest of my life than lose my hold on these emotions.

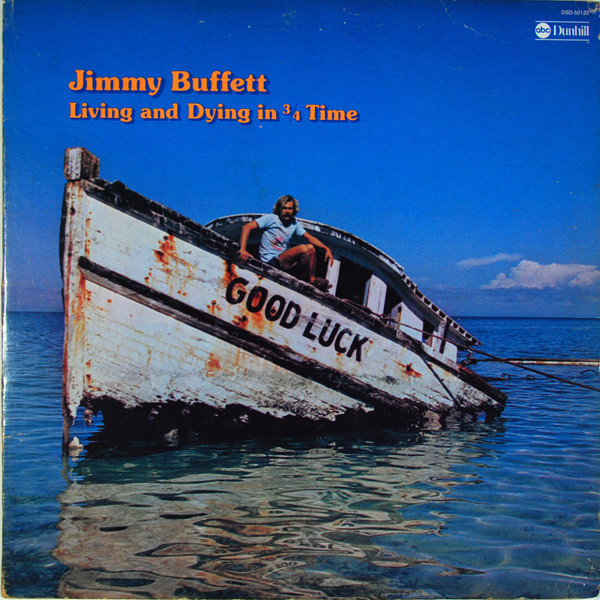

The numbness, though — that bothers me. I want to feel. I want to weep for my child or laugh at a golden memory. I want to feel pain and love and loss and connection, because those keep my vision of Alex fresh and present. Numbness threatens oblivion. Numbness makes the loss seem complete, irretrievable — and that I don’t want. Not ever. Better to cry every day for the rest of my life than lose my hold on these emotions. The news of Jimmy Buffett’s death this past weekend, hit me surprisingly hard, and I am still trying to figure out why. Buffett, the “Roguish Bard of Island Escapism,” as the New York Times called him in an online obituary, was a strong musical presence in my life. I have been listening to his music for more than four decades, I own a bunch of his albums, and over the years I have learned to play many of his songs on my guitars (none of them is particularly difficult to master). But the truth is, if asked to name my top five or top ten or even top twenty-five favorite bands and musicians, he probably wouldn’t make it onto any of those lists. So why do I feel as though I’ve lost a friend?

The news of Jimmy Buffett’s death this past weekend, hit me surprisingly hard, and I am still trying to figure out why. Buffett, the “Roguish Bard of Island Escapism,” as the New York Times called him in an online obituary, was a strong musical presence in my life. I have been listening to his music for more than four decades, I own a bunch of his albums, and over the years I have learned to play many of his songs on my guitars (none of them is particularly difficult to master). But the truth is, if asked to name my top five or top ten or even top twenty-five favorite bands and musicians, he probably wouldn’t make it onto any of those lists. So why do I feel as though I’ve lost a friend?