Forty-one years ago, after an emotionally difficult sophomore year in college, I took a job as a camp counselor at a sleep away camp in rural Pennsylvania. I didn’t want to go home, and I didn’t want to stay in Providence, and I thought a summer of working and living and playing with kids would be good for me. It was, mostly. But that’s not what this post is about.

All the counselors at the camp had two essential duties. First, they were bunk counselors, living with and taking care of kids in a given age group. I was assigned to a bunk of twelve-year-old boys, who, I learned, straddle the line between “kid” and “teen,” ping-ponging from angelic to demonic and back again with breathtaking agility. And second, counselors had a specialty that they taught throughout the summer. I was an avid birdwatcher and nature enthusiast even then, so I was the nature counselor. As it happens, my fellow bunk counselor and I were both named David. He had been at the camp for several years, so he was “Old Dave” and I was “New Dave.” And my colleague in the outdoor program was also named David, so he and I were “Camping Dave” and “Nature Dave.” (It didn’t seem to bother anyone — well, except me — that I didn’t like being called “Dave” then any more than I do now.)

Near the end of the summer, Camping Dave and I organized a sleep-out for any kid or counselor who cared to join us, so that we could watch the peak of the annual Perseid meteor shower. Our plan was to have the kids sleep out on the huge soccer/baseball field, cook s’mores, watch shooting stars, and stay up past their usual bedtimes. Sounds great, right?

Except things didn’t go according to plan.

They went far, far better than we hoped.

Because that night there was a northern lights display that lit up the night sky up and down the eastern part of the United States. My brother was camping in Vermont that same night, and he saw it too. The kids thought it was very cool, though I don’t think they understood how special it was to see what they were seeing. A few were disappointed that the weird, curtains of light in the sky made it impossible to see shooting stars.

Dave and I, and the other counselors who were with us, were thrilled. Most of us had never seen the northern lights before. The glow in the sky was mostly green that night, at least it appeared so from where we were, and it danced and flickered and shimmered for hours before fading well after midnight. To this day, my memories of that night remain vivid and joyful. Before this past Friday night, it was the only time in my life when I saw the aurora borealis.

Friday night, found me in Tennessee rather than Pennsylvania, and yet, in a testament to the power of this year’s solar event, Friday’s display was every bit as spectacular as that first one so many years ago. And yet . . . .

We got our first hint of the possibility of unusually widespread aurora sightings a couple of weeks ago. Astronomers reported an increase in solar flare activity that they thought would soon peak at historic levels. On Friday itself, when the first of the huge flares occurred, scientists again noted that this could mean unusual aurora occurrences.

But those predictions were buried in news reports of quite a different nature. Most of the news outlets neglected to focus on what turned out to be a wondrously beautiful event that linked people all over the globe. Instead, most articles warned of what the sunspot activity and solar wind might do to communications satellites, electric grids, internet providers, and other parts of the electronic infrastructure on which we depend. And hey, I get it. Media outlets and the governmental and scientific institutions to which they turn for information when stuff like this happens don’t want to be caught off guard. They don’t want to be blamed for the dislocations caused by foreseeable problems. So they emphasize the expected bad news and downplay anything that might detract attention from those dire potential consequences.

As it happens, though, the few disruptions caused by Friday’s solar flares turned out to be minor. The real story turned out to be the phenomenal views of auroras enjoyed by people around the world in areas for which such sightings are usually quite rare.

Look, no one who knows me would ever confuse me for a Pollyanna. I am a lifelong pessimist. I am Mister Doom-and-Gloom. I am Eeyore. But Friday night was amazing, a night I will remember for the rest of my life. And I wonder how many people missed their chance to experience it because news of what was going to occur wound up buried in stories about terrible troubles that never materialized. Probably a lot. Which is too bad. Because the collective joy shared, across continents and oceans, by strangers who were fortunate enough to see the auroras, both borealis and australis, was an inspiring, albeit temporary antidote to the doom and gloom that confronts us on a daily basis.

I hope you were among the fortunate who saw the display.

Have a great week.

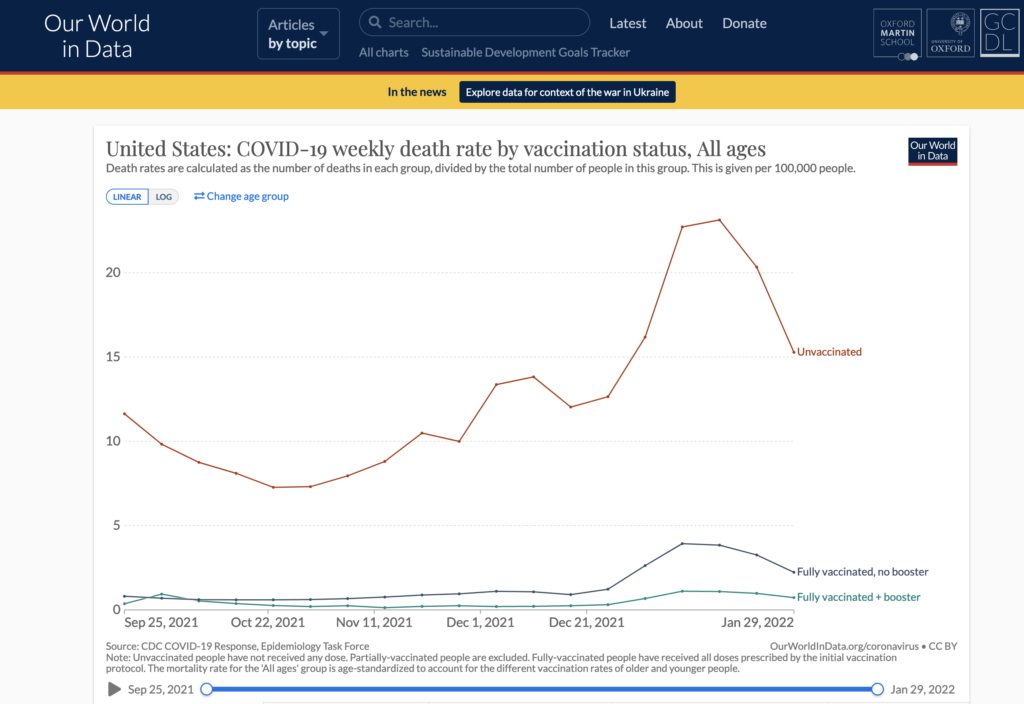

And so those who trust the Covid science will remain safer than those who don’t. Those who keep up with vaccinations and boosters will get sick less often and less severely. They will die in far smaller numbers and spend far less time in the hospital. The numbers are dramatic and indisputable. Sadly, but predictably, living with Covid means accepting an ever widening gap in the rates of infection and in case outcomes between those who ignore the advice of medical professionals and those who follow it. It means accepting that some social and economic disruptions will be unavoidable. One-third of the people in this country are unwilling to protect themselves and their families. There are bound to be consequences for this.

And so those who trust the Covid science will remain safer than those who don’t. Those who keep up with vaccinations and boosters will get sick less often and less severely. They will die in far smaller numbers and spend far less time in the hospital. The numbers are dramatic and indisputable. Sadly, but predictably, living with Covid means accepting an ever widening gap in the rates of infection and in case outcomes between those who ignore the advice of medical professionals and those who follow it. It means accepting that some social and economic disruptions will be unavoidable. One-third of the people in this country are unwilling to protect themselves and their families. There are bound to be consequences for this.