I have a very good friend, also a writer, with whom I often discuss the depressing state of the writing world at this point in history. We have a sort of gallows humor about the whole thing — a lot of joking comments about low pay, the dearth of readers, the way New York publishing has basically lost interest in the midlist author, and the generally low quality of self-published works that we encounter when we dare to dip our toes into those murky waters. (No slight intended to anyone — seriously, if you are self-published, please don’t tell me that I have insulted you. There are good self-published books out there. But let’s be honest: The self-pubbed gems tend to be overwhelmed by the dross. Too many self-published books have had no serious editing or proofing, leaving them overlong and filled with errors that might easily have been avoided.)

Writers starting today face formidable obstacles that did not exist when I began my career (you know, back in the day when we carved novels into stone tablets….). There are more wannabe writers hawking their wares on various online platforms now than there have ever been. The democratization of publishing technology has convinced many that they can be professionals simply by writing something, slapping it into the appropriate app, and putting it up for sale. Again, some of those books might be very good, but none of them have had to make their way through any vetting process. I am a dedicated amateur photographer, and I am pretty good. I have even sold some of my work and had images published. But I am not truly a professional. I know professionals. Most of them are far, far better than I am. But I have access to digital photo equipment that has helped me elevate my skill. I have access to printing services that make my photos look professional. I have even put together a book of my work that looks like any other coffee table photography book. In short, I have benefited from the same sort of democratization in photography that I am describing with respect to publishing, even though I KNOW that I am not nearly as good a photographer as most professionals.

So, anyway, that is one obstacle: The sheer number of authors out there these days, competing for the attention of an ever-shrinking pool of potential readers.

Why ever-shrinking? That’s obstacle number two. I actually think the absolute number of devoted readers has remained roughly the same over the course of the past, say, fifty years. But if that number is remaining relatively static while the population grows, and while the number of would-be authors grows… well, you do the math.

The third obstacle I mentioned above: New York publishing — a moniker used to refer to what some might call legacy publishing — basically means the publishing houses that have dominated the industry for so long: Alfred A. Knopf, Random House, Saint Martins (which includes my old publisher, Tor Books), and other such behemoths. When I started writing, these big publishing houses were still (mostly) independently owned. They ran their businesses with at least some sense of the mission of their founders. They understood that publishing was not simply another profit-maker. The success of big-name authors allowed these houses to nurture the careers of beginning writers, and of those in the so-called midlist who had solid readership but who were probably never going to break into the ranks of those bestsellers. (And allow me to say here that legacy publishing was far from an idyllic business world. Yes, it supported authors in a range of sales categories. But the vast, vast majority of its authors were male and White.) Around the turn of the millennium, New York publishing began to consolidate. Mergers and buyouts disrupted that old model, and when the dust settled, many of the remaining publishing houses were subsidiaries of larger corporations that had no interest in sustaining the careers of authors who didn’t sell all that well. They still gave contracts to the big names, and they still gave contracts to young writers who showed promise, but they had little patience if those young voices didn’t catch on quickly, and they stopped maintaining the midlist pretty much entirely.

The publishers also squeezed out a lot of editors, feeling that editing was a luxury, and an expensive one at that. “Look at all those self-published titles selling online,” they said. “They’re not edited, and their readers don’t seem to care. Why should we spend so much when most readers just aren’t that discerning?” My editor at the start of my career was, to put it mildly, a problematic character. He was difficult to work with, unreliable, and slow. And eventually, he was fired for cause. And yet, I learned a ton from him. He taught me about the business. He taught me to be a much, much better writer, simply by working with me to improve my craft. I would be lying if I didn’t admit that I owe much of my career to his peculiar brand of wisdom. Young writers need that sort of mentorship. And in today’s world, few of them get it.

The publishers also squeezed out a lot of editors, feeling that editing was a luxury, and an expensive one at that. “Look at all those self-published titles selling online,” they said. “They’re not edited, and their readers don’t seem to care. Why should we spend so much when most readers just aren’t that discerning?” My editor at the start of my career was, to put it mildly, a problematic character. He was difficult to work with, unreliable, and slow. And eventually, he was fired for cause. And yet, I learned a ton from him. He taught me about the business. He taught me to be a much, much better writer, simply by working with me to improve my craft. I would be lying if I didn’t admit that I owe much of my career to his peculiar brand of wisdom. Young writers need that sort of mentorship. And in today’s world, few of them get it.

I should also say (in a post that is already lengthy) that today’s young writers also have to compete with a faceless, soulless technology that can produce passable stories at virtually no cost, in virtually no time. How the hell are human authors supposed to compete with that? Yes, AI generated characters and stories are not very good (yet). But again, many readers have come to accept mediocrity as entertainment, so long as it has a plot and serviceable characters. It may not be great, but it will divert my attention for a little while.

And all around us, civilization collapses….

That brings me to the larger point of this post. Last year, at ConCarolinas, I was given the Polaris Award, in large part for the mentoring of young writers I have done, and continue to do. Right now, I have no fewer than half a dozen writers who consider me a mentor. Over the course of my career, that number is far, far higher. I benefited from the wisdom of many established authors when first I began my career. I have always felt that it was my duty, and also my privilege, to offer the same guidance to those coming up after me. I love mentoring.

That brings me to the larger point of this post. Last year, at ConCarolinas, I was given the Polaris Award, in large part for the mentoring of young writers I have done, and continue to do. Right now, I have no fewer than half a dozen writers who consider me a mentor. Over the course of my career, that number is far, far higher. I benefited from the wisdom of many established authors when first I began my career. I have always felt that it was my duty, and also my privilege, to offer the same guidance to those coming up after me. I love mentoring.

But in recent years, I have come to wonder how I can offer encouragement to young writers knowing how difficult a path they face in this profession. I have discussed this at length with the friend I mentioned at the beginning of this post. He feels much the same way, and yet he continues to mentor, too. Why do we do this?

At the risk of speaking on his behalf…. We do everything in our power not to mislead our mentees. We tell them all that I have said in this post about the state of the publishing world. We try to make certain that they understand fully the challenges laid before them. We make sure they know that there are many easier careers available to them, all of them more lucrative. But the truthis, this litany of obstacles usually does little to dissuade them. Which also begs that simple question: Why?

I believe the answer is the same for those seeking mentorship as it is for those of us who mentor. And I find hope in that answer. Storytelling is fundamental to being human. So is the act of receiving stories. Yes, that explains the glutting of the marketplace. But it also explains why so many of us continue to write for a world that seems less and less interested in the tales we create. Many of my friends who are writers tell me that they can’t not write. Writing is an imperative. It is as fundamental to their (our) being as breathing, eating, sleeping. This has been true for me for as long as I can remember. And it is also true for those seeking mentorship today. Just as reading (or listening to books and stories) is essential to those who still seek out books at cons and in bookstores. I have said repeatedly in this post that many readers are not all that discerning. They will accept stories that are just so-so in the absense of anything else. But I also believe that when they encounter a story written with passion and elegance, they recognize it, and they celebrate it.

This is a difficult time for the arts — not just writing, but also music, photography, painting, theater, dance, etc. Our digital world competes with those endeavors for our time, our ears and eyes, our money. And with the digital in our palms all the time, it has a huge advantage. And yet, new creators, with new creations, emerge from obscurity every day. Because at an elemental level, we yearn for art, for story and narrative, for beauty. These things are part of what make us human. I refuse to believe that they won’t remain so for generations to come.

Have a great week.

What about the rest of my life? What’s next in other realms?

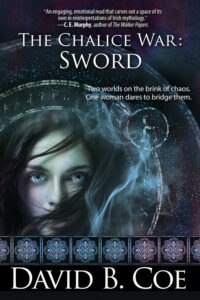

What about the rest of my life? What’s next in other realms? In the last year, I have written two pieces of original short fiction. That’s it. I haven’t written a novel since I finished The Chalice War: Sword, late in 2022. I have recently started work on a tie-in project (I can’t really say more than that, right now), a novel. It is coming slowly, and because I am essentially playing in someone else’s world, the emotions I’ll be mining are somewhat removed from my own. I spent the first half of last year doing a bunch of editing, for myself and for others, figuring that when those projects were through, I would dive into a new book of my own.

In the last year, I have written two pieces of original short fiction. That’s it. I haven’t written a novel since I finished The Chalice War: Sword, late in 2022. I have recently started work on a tie-in project (I can’t really say more than that, right now), a novel. It is coming slowly, and because I am essentially playing in someone else’s world, the emotions I’ll be mining are somewhat removed from my own. I spent the first half of last year doing a bunch of editing, for myself and for others, figuring that when those projects were through, I would dive into a new book of my own. 80,000 people. This year, in an attempt to control the crowd just a little, I believe attendance at the con has been capped at 65,000. Yeah, that’s still pretty big.

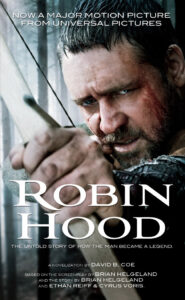

80,000 people. This year, in an attempt to control the crowd just a little, I believe attendance at the con has been capped at 65,000. Yeah, that’s still pretty big. But the media work I have done in the past wasn’t like that. Back in 2009-2010, I wrote the novelization of Ridley Scott’s movie Robin Hood, starring Russell Crowe and Cate Blanchett. The movie wasn’t out yet — I worked from a script — and I didn’t know whether or not I would love it. (I didn’t.) In 2018, I wrote a novel that tied in with the History Channel’s Knightfall series about the Knights Templar. In this case, I got to see all the episodes of the first season before the series was aired. I liked the show well enough.

But the media work I have done in the past wasn’t like that. Back in 2009-2010, I wrote the novelization of Ridley Scott’s movie Robin Hood, starring Russell Crowe and Cate Blanchett. The movie wasn’t out yet — I worked from a script — and I didn’t know whether or not I would love it. (I didn’t.) In 2018, I wrote a novel that tied in with the History Channel’s Knightfall series about the Knights Templar. In this case, I got to see all the episodes of the first season before the series was aired. I liked the show well enough. With the Knightfall book, I had a good deal more freedom and control, and so I enjoyed the process much, much more. But still I was mostly writing from the viewpoint of someone else’s characters. There is one point of view character, though, who I made my own — a child who appears later in the series as an adult. But her childhood POV was mine and gave me that sense of ownership, of personal investment in the book.

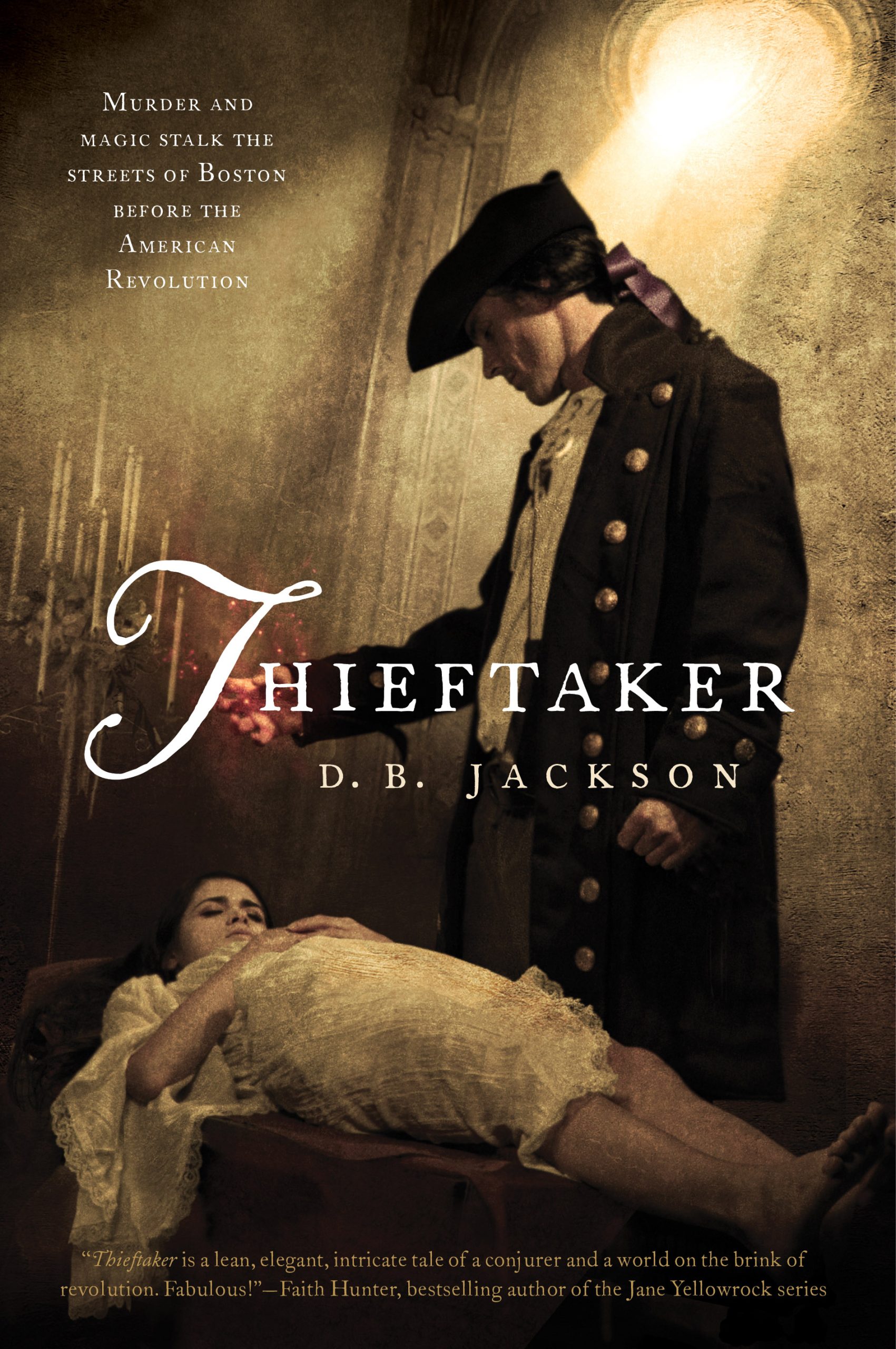

With the Knightfall book, I had a good deal more freedom and control, and so I enjoyed the process much, much more. But still I was mostly writing from the viewpoint of someone else’s characters. There is one point of view character, though, who I made my own — a child who appears later in the series as an adult. But her childhood POV was mine and gave me that sense of ownership, of personal investment in the book. I have written a lot of books and stories over the years. The truth is, I love all of them. I can tell you a hundred things I like about every book I’ve published, and I believe if I could convince people to read each of them, the books would be very popular. But the fact is, as is true with most authors, some of my books have done far better commercially than others. And, as it happens, the ones that have tended to do well are those that are most easily and succinctly described. The Thieftaker books are my most successful. How do I pitch them to interested readers? “These are magical mysteries set against the backdrop of the American Revolution.” The new series, the Chalice War, is also easy to describe — “It’s a modern urban fantasy steeped in Celtic mythology.” These books, I have found, are as easy to sell as the Thieftaker books, and that is saying something.

I have written a lot of books and stories over the years. The truth is, I love all of them. I can tell you a hundred things I like about every book I’ve published, and I believe if I could convince people to read each of them, the books would be very popular. But the fact is, as is true with most authors, some of my books have done far better commercially than others. And, as it happens, the ones that have tended to do well are those that are most easily and succinctly described. The Thieftaker books are my most successful. How do I pitch them to interested readers? “These are magical mysteries set against the backdrop of the American Revolution.” The new series, the Chalice War, is also easy to describe — “It’s a modern urban fantasy steeped in Celtic mythology.” These books, I have found, are as easy to sell as the Thieftaker books, and that is saying something. The three books of the Case Files of Justis Fearsson and the Radiants duology might well be my favorites of all the books I’ve written. They are exciting, emotional, filled with great characters, and paced within an inch of their lives. But they are far more difficult to describe in a single sentence than other books and, likely as a result, they have never done as well commercially as I hoped they would.

The three books of the Case Files of Justis Fearsson and the Radiants duology might well be my favorites of all the books I’ve written. They are exciting, emotional, filled with great characters, and paced within an inch of their lives. But they are far more difficult to describe in a single sentence than other books and, likely as a result, they have never done as well commercially as I hoped they would.