As I discussed at length in last week’s Professional Wednesday post, I have recently completed a first draft of the third book in my contemporary Celtic urban fantasy, The Chalice Wars. The novel needs to sit for a while before I can do a final revise-and-polish and send it off to my editor — six weeks or so, I would think. And since the first book has not yet been copyedited and proofed, since the second book still needs to go through a round of revisions and then the entire production process, and since the third book is still wet behind the ears, I have plenty of work left to do on this series.

Thanks to the successful Kickstarter campaign Zombies Need Brains ran late in the summer, I also have a new anthology, Artifice and Craft, to co-edit with my good friend Edmund Schubert. We already have more than 150 submissions for the anthology, so that work is bound to keep me busy through the end of the year and well into 2023. I also have a short story to write for one of the other anthologies, and I have editing clients in my free-lance business queue.

But beyond the short story, which should only take me a week or two to complete, I have no idea what I am going to write next. None.

Yes, I have ideas. Many.

What are they? Funny you should ask.

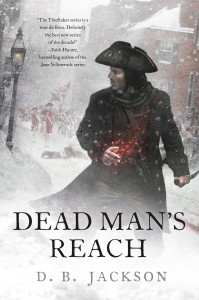

One idea is to write my next Thieftaker novel, either in the form of a trio of novellas, like I did with The Loyalist Witch, or as a simple novel. In the Thieftaker novel timeline, the Revolutionary War hasn’t even started yet. There is lots and lots more I can do with Ethan and Kannice and Sephira.

One idea is to write my next Thieftaker novel, either in the form of a trio of novellas, like I did with The Loyalist Witch, or as a simple novel. In the Thieftaker novel timeline, the Revolutionary War hasn’t even started yet. There is lots and lots more I can do with Ethan and Kannice and Sephira.

I have also considered going back to the Case Files of Justis Fearsson series, another contemporary urban fantasy that I began in the mid 2010s with Spell Blind, His Father’s Eyes, and Shadow’s Blade. I LOVE these books and have missed writing in Justis Fearsson’s world. I have several ideas brewing for that world.

I have long wanted to return to my five book Winds of the Forelands series and the Blood of the Southlands trilogy, to revise and re-release those eight novels. They are among my best stories, and they have been out of print for far too long. I envision an “Author’s Edit” re-issue, along the lines of what I did with the LonTobyn Chronicle back in 2016.

I want to write at least one more Radiants book. Actually, I would like to write several more. Radiants and Invasives are, to my mind, the two best books I’ve written to date, and I still would love to see these books gain come commercial traction so that I can justify writing more of them.

I want to write at least one more Radiants book. Actually, I would like to write several more. Radiants and Invasives are, to my mind, the two best books I’ve written to date, and I still would love to see these books gain come commercial traction so that I can justify writing more of them.

And then there are the new ideas . . .

I have one idea for a space opera series (yes, you read that right), set on a pair of terraformed planets. The plot involves intrigue, mystery, romance, and vengeance, and it is actually based on the work of a well-known, much-beloved, and for-now-secret 19th century novelist. I’m excited about this one. (Actually, I’m excited about all these ideas, which is why I’m considering them in the first place.)

I have a middle grade novel that I first wrote back in 2010 or so, when my kids were much younger. The idea still sings to me, though I know the book needs a good deal of work. But I love the concept and I adore the characters. And I think I would enjoy writing for kids.

My good friend A.J. Hartley has been trying for years to get me to write a non-fantasy, non-supernatural, straight-ahead thriller. He thinks I’d enjoy it. He thinks I’d be good at it. And I will admit I have some ideas percolating along these lines as well. Of all the projects I’m thinking about, this one probably has the most commercial potential, which is not the only consideration, but I do this for a living, so . . . .

And finally, I have considered taking all the Professional Wednesday and Writing Wednesday posts I have written since 2020 and collecting the best of them in a new writing how-to book. I have more than enough material, and I think some people would like to see the advice I have offered gathered in a single, convenient volume.

So there we are. Those are the things I’m thinking about right now. (I should add that I can’t guarantee I won’t have five more ideas tomorrow.)

What ideas appeal to you? Feel free to Tweet at me, or to comment in my Facebook Group! I look forward to hearing your thoughts.

In the meantime, keep writing!

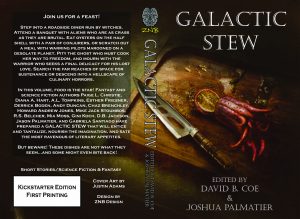

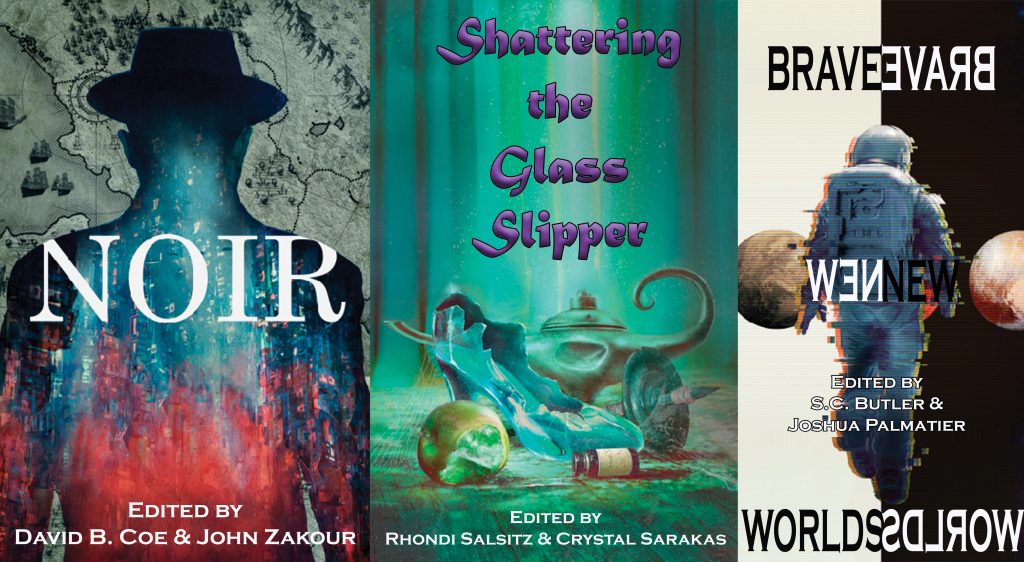

This will be the fifth anthology I have edited for ZNB (after

This will be the fifth anthology I have edited for ZNB (after  Since writing it, though, I have become sort of fixated on the idea. I am editing my fourth anthology, and already looking at the possibility of editing another. My freelance editing business is attracting a steady stream of clients — I’m booked through the spring and have had inquiries for slots later in the year.

Since writing it, though, I have become sort of fixated on the idea. I am editing my fourth anthology, and already looking at the possibility of editing another. My freelance editing business is attracting a steady stream of clients — I’m booked through the spring and have had inquiries for slots later in the year. I am not an acquiring editor. I do decide, along with my co-editor, whose stories will be in the anthologies I edit, so I suppose in that way I am determining the fate of submissions and, in a sense, “buying” manuscripts. But, for now at least, I don’t make decisions about the fate of novels, and so I don’t have to go toe-to-toe with agents. Good thing. They scare me. (Looking at you, Lucienne Diver.)

I am not an acquiring editor. I do decide, along with my co-editor, whose stories will be in the anthologies I edit, so I suppose in that way I am determining the fate of submissions and, in a sense, “buying” manuscripts. But, for now at least, I don’t make decisions about the fate of novels, and so I don’t have to go toe-to-toe with agents. Good thing. They scare me. (Looking at you, Lucienne Diver.) I am not the most talented writer I know. Not by a long shot. I am good. I believe that. My character work is strong. My world building is imaginative. My prose is clean and tight and it flows nicely. I write convincing, effective dialogue and I have a fine eye for detail. My plotting and pacing, which were once just okay, have gotten stronger over the years. I think writing the Thieftaker books — being forced to blend my fictional plots with real historical events — forced me to improve, and that improvement has shown up in the narratives of the Islevale and Radiants books.

I am not the most talented writer I know. Not by a long shot. I am good. I believe that. My character work is strong. My world building is imaginative. My prose is clean and tight and it flows nicely. I write convincing, effective dialogue and I have a fine eye for detail. My plotting and pacing, which were once just okay, have gotten stronger over the years. I think writing the Thieftaker books — being forced to blend my fictional plots with real historical events — forced me to improve, and that improvement has shown up in the narratives of the Islevale and Radiants books. As many of you know, I am once again co-editing an anthology for

As many of you know, I am once again co-editing an anthology for  I discussed the Thieftaker books in last week’s post, and I mentioned how my love of U.S. history steered me toward setting the series in pre-Revolutionary Boston. But I failed to mention then that upon deciding to set the books in 1760s Boston, I then had to dive into literally months of research. Sure, I had read colonial era history for my Ph.D. exams, but I had never looked at the period the way I would need to in order to use it as a setting for a novel, much less several novels and more than a dozen pieces of short fiction. Ironically, as a fiction author I needed far more basic factual information about the city, about the time period, about the historical figures who would appear in my narratives, than I ever did as a doctoral candidate.

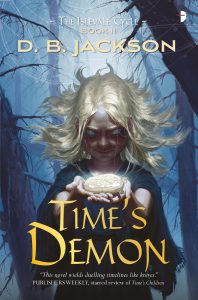

I discussed the Thieftaker books in last week’s post, and I mentioned how my love of U.S. history steered me toward setting the series in pre-Revolutionary Boston. But I failed to mention then that upon deciding to set the books in 1760s Boston, I then had to dive into literally months of research. Sure, I had read colonial era history for my Ph.D. exams, but I had never looked at the period the way I would need to in order to use it as a setting for a novel, much less several novels and more than a dozen pieces of short fiction. Ironically, as a fiction author I needed far more basic factual information about the city, about the time period, about the historical figures who would appear in my narratives, than I ever did as a doctoral candidate. The same is true of the worlds I build from scratch for my novels. My most recent foray into wholesale world building was the prep work I did for my Islevale Cycle, the time travel/epic fantasy books I wrote a few years ago. As with my Thieftaker research, my world building for the Islevale trilogy consumed months. I began (as I do with my research) with a series of questions about the world, things I knew I had to work out before I could write the books. How did the various magicks work? What were the relationships among the various island nations? Where did my characters fit into these dynamics? Etc.

The same is true of the worlds I build from scratch for my novels. My most recent foray into wholesale world building was the prep work I did for my Islevale Cycle, the time travel/epic fantasy books I wrote a few years ago. As with my Thieftaker research, my world building for the Islevale trilogy consumed months. I began (as I do with my research) with a series of questions about the world, things I knew I had to work out before I could write the books. How did the various magicks work? What were the relationships among the various island nations? Where did my characters fit into these dynamics? Etc. These are books I turn to again and again during the course of my work, and I expect the writer on your list will do the same. Not all of them are easy to find, but I assure you, they’re worth the effort. So here is a partial list:

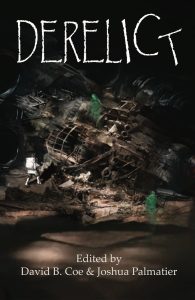

These are books I turn to again and again during the course of my work, and I expect the writer on your list will do the same. Not all of them are easy to find, but I assure you, they’re worth the effort. So here is a partial list: Last year, I co-edited Derelict. We received more than four hundred stories. The year before, I co-edited Galactic Stew. We received more than four hundred stories. The year before that, I co-edited Temporally Deactivated. We received more than two-hundred and fifty stories. Again, these are submissions for a total of six or seven slots.

Last year, I co-edited Derelict. We received more than four hundred stories. The year before, I co-edited Galactic Stew. We received more than four hundred stories. The year before that, I co-edited Temporally Deactivated. We received more than two-hundred and fifty stories. Again, these are submissions for a total of six or seven slots.