It’s been a little over three weeks since Alex, our older daughter, lost her two and a half year battle with cancer. It feels like more. It feels like less.

We have had celebrations of her life in New York City and in our little home town in Tennessee. Both were crowded and loud and fun. Both were filled with laughter and tears, music and good food, and lots and lots of remembrances of our brilliant, funny, beautiful child. (Yes, she was 28. Still, she will always be our child, our first baby, our darling little girl.) We have been overwhelmed by the love shown us by friends and family near and distant. By the generosity — spiritual, emotional, material — of so many. Cards, gifts, flowers, food, phone calls, and texts. And yes, comments by the hundreds on social media posts. We are humbled and grateful beyond words for every expression of support and sympathy. Thank you a thousand times.

At this point, the celebrations of her life are over. Guests from out of town have left. Erin has gone back home. Nancy is starting to work again, and I am gearing up to do the same. We are, I suppose, stepping back into “normal” life. Except there is nothing normal about it, and in ways that truly matter, in ways that will remain with us for the rest of our lives, it will never really be normal at all, ever again.

At this point, the celebrations of her life are over. Guests from out of town have left. Erin has gone back home. Nancy is starting to work again, and I am gearing up to do the same. We are, I suppose, stepping back into “normal” life. Except there is nothing normal about it, and in ways that truly matter, in ways that will remain with us for the rest of our lives, it will never really be normal at all, ever again.

How do we navigate this path? I honestly don’t know. It’s a terrible cliché, but I guess we do so one day at a time, one moment at a time, one breath at a time. In and out. Take a step. And breathe again. Rinse, repeat.

It’s a good thought, I suppose. It feels inadequate to the task. Already, in just these few weeks, I have reached for my phone more times than I can count, intending to text Alex, or check for a text from her. I want desperately to hear her voice, to know once again the music of her laughter, to ask her questions about her work, or the new restaurant she’s tried out most recently, or the music she currently has on looped-play. And each time, reality kicks me in the gut.

I watch TV and am shocked by the number of times some character, on-screen or off, is said to have cancer. There is no escaping it. We hear news of a celebrity passing away — cancer again. News of lost children assaults us from all corners of the globe, wars claiming their collateral toll, gun violence here in the States stealing more innocent young lives. These tidings were always awful to hear, but they were abstract in some way. Anonymous. Not anymore. Children are lost. Parents grieve. We are members of a club no parent wants to join.

Alex’s death hit so many people so hard, and in one sense that was a product of her amazing personality, her magnetism. But I am wise enough to understand that there is far more to it than that. The outpouring of love and grief from her friends comes in part from the simple truth that, for many of them, she is the first of their contemporaries to die. Tragedy has breached their generational line far too soon, and they are shell-shocked. The outpouring of love and grief from our friends comes in part from the recognition that this is every parent’s nightmare. Losing one’s child is unthinkable, unimaginable, unendurable. It happens, of course. Too often, actually. That club has more members than we ever knew. Several have reached out to me to say so, and to offer support and guidance. But for so many, our loss is a terrifying echo of their deepest unspoken fear.

Another truth: After Alex’s diagnosis in March of 2021, I found myself imagining the worst all the time. I couldn’t stop myself. Therapy helped some, but not completely. I lived with the constant dread of this ending, with the unrelenting awareness of the odds against her, of the near inevitability of her decline. Unimaginable? Hardly.

These days, I’m often asked, “How are you doing?” I don’t know how to answer. My emotions are in constant flux. At times I feel okay, and I can see a way forward. Other times I feel numb. And still others I am as fragile as spring ice. One wrong step and I’ll shatter. This is normal, I know. Grief is not linear. It can’t be prescribed, and while breaking it down into stages might appear to clarify the maelstrom of feelings raging around me, the construct strikes me as artificial and less than helpful. I know better than to be seduced by those moments when I feel as though I have a handle on my loss. I sense that I will get there eventually, but I’m not there yet, and won’t be for a long time. I also know better than to panic when I feel out of control. That will pass as well.

The numbness, though — that bothers me. I want to feel. I want to weep for my child or laugh at a golden memory. I want to feel pain and love and loss and connection, because those keep my vision of Alex fresh and present. Numbness threatens oblivion. Numbness makes the loss seem complete, irretrievable — and that I don’t want. Not ever. Better to cry every day for the rest of my life than lose my hold on these emotions.

The numbness, though — that bothers me. I want to feel. I want to weep for my child or laugh at a golden memory. I want to feel pain and love and loss and connection, because those keep my vision of Alex fresh and present. Numbness threatens oblivion. Numbness makes the loss seem complete, irretrievable — and that I don’t want. Not ever. Better to cry every day for the rest of my life than lose my hold on these emotions.

And so I stumble onward, trying to figure it all out, hurting and remembering and loving most of all. I don’t know when I will post again. Soon, I hope. I believe writing this has helped, and I am certain I will have more to write in the days, weeks, and months to come. Thank you for reading. Thank you for your sympathy and friendship, and also for your continued patience and respect of our privacy as we attempt to find our way.

Hug those you love.

This is the post I never wanted to write. The one I dreaded, the one that was, not so long ago, unthinkable, and, more recently, heartrendingly inevitable.

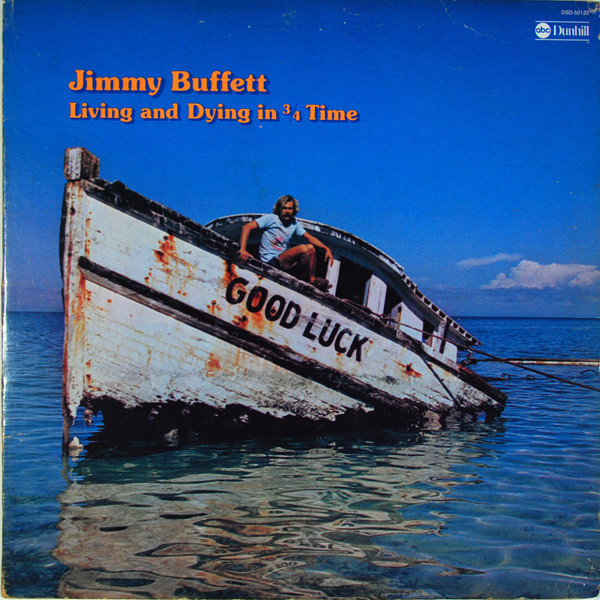

This is the post I never wanted to write. The one I dreaded, the one that was, not so long ago, unthinkable, and, more recently, heartrendingly inevitable. The news of Jimmy Buffett’s death this past weekend, hit me surprisingly hard, and I am still trying to figure out why. Buffett, the “Roguish Bard of Island Escapism,” as the New York Times called him in an online obituary, was a strong musical presence in my life. I have been listening to his music for more than four decades, I own a bunch of his albums, and over the years I have learned to play many of his songs on my guitars (none of them is particularly difficult to master). But the truth is, if asked to name my top five or top ten or even top twenty-five favorite bands and musicians, he probably wouldn’t make it onto any of those lists. So why do I feel as though I’ve lost a friend?

The news of Jimmy Buffett’s death this past weekend, hit me surprisingly hard, and I am still trying to figure out why. Buffett, the “Roguish Bard of Island Escapism,” as the New York Times called him in an online obituary, was a strong musical presence in my life. I have been listening to his music for more than four decades, I own a bunch of his albums, and over the years I have learned to play many of his songs on my guitars (none of them is particularly difficult to master). But the truth is, if asked to name my top five or top ten or even top twenty-five favorite bands and musicians, he probably wouldn’t make it onto any of those lists. So why do I feel as though I’ve lost a friend? My mind has been on Title IX again over the past month, as Nancy and I (and our daughters, while we were all together in Colorado) watched the Women’s World Cup. Soccer has long been a very big deal in our household. Our daughters grew up playing, first in weekend league soccer and then through middle school and high school. Both of them were accomplished players. Both of them continue to love the sport. And so we all look forward to the World Cup — men’s and women’s — the way we look forward to holidays and birthdays.

My mind has been on Title IX again over the past month, as Nancy and I (and our daughters, while we were all together in Colorado) watched the Women’s World Cup. Soccer has long been a very big deal in our household. Our daughters grew up playing, first in weekend league soccer and then through middle school and high school. Both of them were accomplished players. Both of them continue to love the sport. And so we all look forward to the World Cup — men’s and women’s — the way we look forward to holidays and birthdays. World Cup soccer — men’s and women’s — begins with what is called group play. The field of thirty-two is divided into eight groups of four. Each group plays among themselves, three matches for each team, and they get three points for a win, one point for a draw, and none for a loss. The two teams with the best record from each group advance to the knockout stage, so called because there are no ties, and the loser of each match is knocked out of the competition.

World Cup soccer — men’s and women’s — begins with what is called group play. The field of thirty-two is divided into eight groups of four. Each group plays among themselves, three matches for each team, and they get three points for a win, one point for a draw, and none for a loss. The two teams with the best record from each group advance to the knockout stage, so called because there are no ties, and the loser of each match is knocked out of the competition. Despite American disappointment, these developments actually constitute incredibly good news for women’s soccer around the world. Title IX paved the way for the U.S. women to become a dominant team, and in many European nations, where traditional football is THE sport, women’s teams have access to facilities and funding. But in other places this is simply not the case. The Jamaican woman faced so many financial hardships in their preparation for this year’s Cup that they literally had to rely on crowdfunding in order to participate.

Despite American disappointment, these developments actually constitute incredibly good news for women’s soccer around the world. Title IX paved the way for the U.S. women to become a dominant team, and in many European nations, where traditional football is THE sport, women’s teams have access to facilities and funding. But in other places this is simply not the case. The Jamaican woman faced so many financial hardships in their preparation for this year’s Cup that they literally had to rely on crowdfunding in order to participate. I spent this past weekend going through my photos, processing the images, and selecting a few to put in a rotation of favorites that show up on my computer desktop and in my screensaver slide show. And as I work through these images, I have been thinking about photography in general and where the technology that is now available to photography hobbyists has taken us.

I spent this past weekend going through my photos, processing the images, and selecting a few to put in a rotation of favorites that show up on my computer desktop and in my screensaver slide show. And as I work through these images, I have been thinking about photography in general and where the technology that is now available to photography hobbyists has taken us. Some stores and processing centers were willing to consider special instructions — “please over- (or under-) expose slightly” or some such. But to be honest, I wasn’t good enough at that point to know with confidence that ALL my images would need the same special treatment, and so I just sent my film in and hoped for the best. More often than not, I was disappointed.

Some stores and processing centers were willing to consider special instructions — “please over- (or under-) expose slightly” or some such. But to be honest, I wasn’t good enough at that point to know with confidence that ALL my images would need the same special treatment, and so I just sent my film in and hoped for the best. More often than not, I was disappointed. Knowing what I do about the history of photography, I now understand how strange that consumer film process actually was. The old masters of photography — Edward Weston, Alfred Stieglitz, and most notably Ansel Adams did not leave it to Kodak or Fujifilm or any other commercial entity to develop their images. They held fast to every step of the creative process, from image capture to production of the final print. Photography as an art form was not limited to a mechanical blink of creative inspiration. Rather, it relied upon a complex and time-consuming manipulation of that initial capture, to turn the photo into exactly what the artist envisioned. Adams in particular used an approach he called “dodge and burn,” relying on a masterful understanding of darkroom tools and chemicals to darken certain parts of an image and brighten others. He and his contemporaries would never have dreamed of placing themselves at the mercy of film development labs.

Knowing what I do about the history of photography, I now understand how strange that consumer film process actually was. The old masters of photography — Edward Weston, Alfred Stieglitz, and most notably Ansel Adams did not leave it to Kodak or Fujifilm or any other commercial entity to develop their images. They held fast to every step of the creative process, from image capture to production of the final print. Photography as an art form was not limited to a mechanical blink of creative inspiration. Rather, it relied upon a complex and time-consuming manipulation of that initial capture, to turn the photo into exactly what the artist envisioned. Adams in particular used an approach he called “dodge and burn,” relying on a masterful understanding of darkroom tools and chemicals to darken certain parts of an image and brighten others. He and his contemporaries would never have dreamed of placing themselves at the mercy of film development labs. More, I no longer have to decide before going out in the field what sort of film to use. I can take an image that I know will work in color and follow it up immediately with one that I know I’ll prefer in black and white. Converting an image from color to grayscale is as simple as clicking a box. I love that freedom.

More, I no longer have to decide before going out in the field what sort of film to use. I can take an image that I know will work in color and follow it up immediately with one that I know I’ll prefer in black and white. Converting an image from color to grayscale is as simple as clicking a box. I love that freedom.