I lived in Providence, Rhode Island for six years, four of them as a student at Brown University. To this day, many of my closest friends are those I met at Brown. The campus, and the beautiful neighborhoods around it, remain fresh in my memory. I wasn’t always happy there — I’m not so far gone down a nostalgic rabbit-hole as to make such a claim. I was navigating those perilous years between adolescence and adulthood. I had ups and downs, heartaches and moments of deep joy. But I consider Providence, and College Hill in particular, one of the true homes I’ve had.

The images that poured out of Providence this past Saturday night were shocking and terrifying. Another shooting at another American college. I knew it was possible that Brown would find its way onto that terrible list, along with Virginia Tech and UNC-Charlotte, University of California Santa Barbara and University of Nevada Las Vegas, Michigan State and Florida State and Kentucky State, University of Virginia and Northern Arizona University, and more, and more, and more, but I always hoped my alma mater would somehow be immune. To be honest, though, I worried more about the university where Nancy taught and worked. I worried about that nearly every day. It’s a terrible thing to live in a country where these fears are present all the time, in every corner of the nation. That is the price we pay for an ill-advised Constitutional Amendment written two hundred and forty years ago that has been selectively misinterpreted throughout its history and exploited again and again by a billion-dollar firearms industry.

Hours after the shooting at Brown, another shooting, this one targeting a Hanukkah celebration at Bondi Beach in Sydney, Australia left more than fifteen dead and dozens more wounded. I’ve been to Bondi Beach. We lived in Australia for a year when the girls were young and Nancy was on sabbatical. And this weekend, we began lighting our menorah to celebrate Hanukkah. The tragedies in Providence and Sydney have struck far, far too close to home.

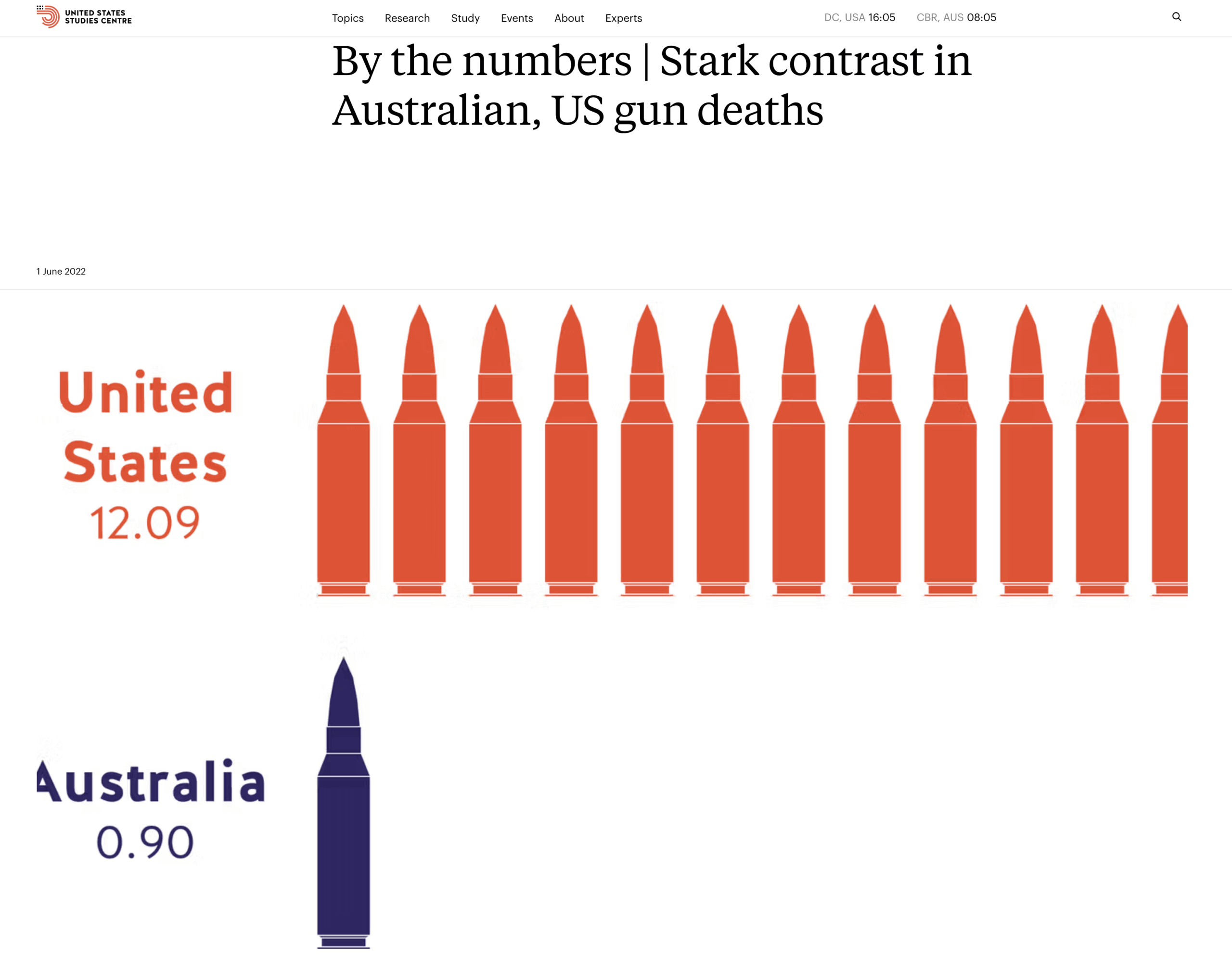

I know that gun rights activists here in the U.S. will point to the events in Sydney as proof that strict gun controls don’t work as a deterrent to gun violence. This is a little like pointing to a single car wreck in which a seat-belted driver dies as evidence that seat belt laws don’t save lives. Yes, Australia has firearms control in place, and yes people were shot and killed there anyway. The difference, as one observer pointed out over the weekend, is that the shooting in Australia was the worst in that country in close to 30 years. The shooting at Brown was the worst in the U.S. in the past two weeks…. Gun deaths in the U.S. are twelve times more common than they are in Australia. Twelve times. And yes, that’s calculated on a per capita basis. The raw numbers are far, far more stunning. In 2023, 31 Australians were victims of gun-related homicides. In the U.S., the number was 17,927. Add in gun-related suicides and accidents, and in 2023 the U.S. had nearly 47,000 gun deaths. That is insanity.

This is not the first post of this sort I have written. Not even close. And I am depressingly certain that it won’t be the last. The solution is as obvious as it is unattainable. I don’t believe that Americans are born with a greater proclivity for violence than are the Australians, or the English, or the French, or the Spanish, or the Italians, or the Swedes, or the Finns, or the Danes, or the Dutch, or the Kiwis, etc., etc., etc. I do believe that we live in a culture that promotes gun violence, and I know that the availability of guns in this country — there are enough privately owned guns in the U.S. to arm every adult and child in the country and still have enough to also arm all the people in Japan — feeds our obscene rate of gun violence.

But nearly every Republican member of the House and Senate, and a substantial number of the Democrats as well, are beholden to the gun industry and pro-firearms lobbying groups. The Second Amendment isn’t going the way of Prohibition any time soon. Which means the killings will continue, feckless politicians will offer meaningless “thoughts and prayers,” and yet another generation of children will grow up being tutored in “live shooter” protocols and shelter-in-place procedures. The specter of gun violence will haunt them throughout elementary, middle, and high school. And yes, it will follow them when they go to college. The happiest years of their lives? Good lord, I hope not.

Stay safe. Hug the people you love.

Last weekend, at ConCarolinas, I was honored with the Polaris Award, which is given each year by the folks at Falstaff Books to a professional who has served the community and industry by mentoring young writers (young career-wise, not necessarily age-wise). I was humbled and deeply grateful. And later, it occurred to me that early in my career, I would probably have preferred a “more prestigious” award that somehow, subjectively, declared my latest novel or story “the best.” Not now. Not with this. I was, essentially, being recognized for being a good person, someone who takes time to help others. What could possibly be better than that?

Last weekend, at ConCarolinas, I was honored with the Polaris Award, which is given each year by the folks at Falstaff Books to a professional who has served the community and industry by mentoring young writers (young career-wise, not necessarily age-wise). I was humbled and deeply grateful. And later, it occurred to me that early in my career, I would probably have preferred a “more prestigious” award that somehow, subjectively, declared my latest novel or story “the best.” Not now. Not with this. I was, essentially, being recognized for being a good person, someone who takes time to help others. What could possibly be better than that? Our beloved older daughter would have been thirty years old today.

Our beloved older daughter would have been thirty years old today. Later we realized that the name was too small to contain her, too simple to encompass all that she was, all that she would grow to be. She might have been the smallest in her class, but she was smart as hell and personable, with a huge, charismatic personality. She might have been the smallest on her teams, but she was fast and savvy and utterly fearless. On the soccer pitch and in the swimming pool, she was fierce and hard-working. Size didn’t matter. She might have been the smallest on stage, but she danced with passion and joy and grace, and, when appropriate, with a smile that blazed like burning magnesium.

Later we realized that the name was too small to contain her, too simple to encompass all that she was, all that she would grow to be. She might have been the smallest in her class, but she was smart as hell and personable, with a huge, charismatic personality. She might have been the smallest on her teams, but she was fast and savvy and utterly fearless. On the soccer pitch and in the swimming pool, she was fierce and hard-working. Size didn’t matter. She might have been the smallest on stage, but she danced with passion and joy and grace, and, when appropriate, with a smile that blazed like burning magnesium. One time, in a soccer match against a hated rival, a player from the other team, a huge athlete nearly twice Alex’s size, grew tired of watching Alex’s back as she sped down the touchline on another break. So she fouled Alex. Hard. Slammed into her and sent her tumbling to the ground. I didn’t have time to worry about my kid. Because Alex bounced up while the ref’s whistle was still sounding, and wagged a finger at the girl. “Oh, no you don’t,” that finger-wag said. “You can’t intimidate me.”

One time, in a soccer match against a hated rival, a player from the other team, a huge athlete nearly twice Alex’s size, grew tired of watching Alex’s back as she sped down the touchline on another break. So she fouled Alex. Hard. Slammed into her and sent her tumbling to the ground. I didn’t have time to worry about my kid. Because Alex bounced up while the ref’s whistle was still sounding, and wagged a finger at the girl. “Oh, no you don’t,” that finger-wag said. “You can’t intimidate me.” She was effortlessly cool, like her uncle Bill — my oldest brother. And she had a wicked sense of humor. She was brilliant and beautiful. She loved to travel. She loved music and film and literature. She was passionate in her commitment to social justice. She adored her younger sister. And she was without a doubt the most courageous soul I have ever known.

She was effortlessly cool, like her uncle Bill — my oldest brother. And she had a wicked sense of humor. She was brilliant and beautiful. She loved to travel. She loved music and film and literature. She was passionate in her commitment to social justice. She adored her younger sister. And she was without a doubt the most courageous soul I have ever known. When Alex was three years old, Nancy took a sabbatical semester in Quebec City, at the Université Laval. I stayed in Tennessee, where I was overseeing the construction of what would become our first home. Once Nancy found a place for them to live, I brought Alex up to her and helped the two of them settle in. In part, that meant finding a day-school for Alex so that Nancy could conduct her research. We put her in a Montessori school that seemed very nice, but was entirely French-speaking. The first morning, Alex was in tears, scared of a place she didn’t know, among people she could scarcely understand. But we knew she would love it eventually, and as young parents, we had decided this was best. So we explained to her as best we could that we would be back in a few hours, that the people there would take good care of her, and that this was something we needed for her to do. I will never forget walking away from the school, with tiny Alex standing at the window, tears streaming down her face as she waved goodbye to us. And I remember thinking then, “She is the bravest person I know.” Remember, Alex, all of three years old, didn’t speak a word of French!!

When Alex was three years old, Nancy took a sabbatical semester in Quebec City, at the Université Laval. I stayed in Tennessee, where I was overseeing the construction of what would become our first home. Once Nancy found a place for them to live, I brought Alex up to her and helped the two of them settle in. In part, that meant finding a day-school for Alex so that Nancy could conduct her research. We put her in a Montessori school that seemed very nice, but was entirely French-speaking. The first morning, Alex was in tears, scared of a place she didn’t know, among people she could scarcely understand. But we knew she would love it eventually, and as young parents, we had decided this was best. So we explained to her as best we could that we would be back in a few hours, that the people there would take good care of her, and that this was something we needed for her to do. I will never forget walking away from the school, with tiny Alex standing at the window, tears streaming down her face as she waved goodbye to us. And I remember thinking then, “She is the bravest person I know.” Remember, Alex, all of three years old, didn’t speak a word of French!! Her dauntlessness served her well on the pitch and in the pool, on stage and in the classroom. It fed an adventuresome spirit that took her to Costa Rica for a semester in high school, to the top of Mount Rainier with a summer outdoor program, to a successful four years at NYU, to Germany for part of her sophomore year in college, to Spain for all of her junior year in college, and on countless side-trips all over Europe.

Her dauntlessness served her well on the pitch and in the pool, on stage and in the classroom. It fed an adventuresome spirit that took her to Costa Rica for a semester in high school, to the top of Mount Rainier with a summer outdoor program, to a successful four years at NYU, to Germany for part of her sophomore year in college, to Spain for all of her junior year in college, and on countless side-trips all over Europe. She was, in short, remarkable. I loved her more than I can possibly say. I also admired her deeply. To this day, I push myself to do things that might make me uncomfortable or afraid by telling myself, “Alex would do it, and she’d want me to do it as well.”

She was, in short, remarkable. I loved her more than I can possibly say. I also admired her deeply. To this day, I push myself to do things that might make me uncomfortable or afraid by telling myself, “Alex would do it, and she’d want me to do it as well.”

Clara Bartels was born in Amsterdam and came to the United States as a small child. Her father was a diamond cutter, and diamond cutters were in great demand in the diamond district of New York City. She grew up around the block from Jacques Cohen, who later in life changed the family’s last name to Coe, and whose father also was a diamond cutter who emigrated from Amsterdam. They would marry, have three kids, and then divorce, bitterly, at a time when divorce was not really something people were supposed to do.

Clara Bartels was born in Amsterdam and came to the United States as a small child. Her father was a diamond cutter, and diamond cutters were in great demand in the diamond district of New York City. She grew up around the block from Jacques Cohen, who later in life changed the family’s last name to Coe, and whose father also was a diamond cutter who emigrated from Amsterdam. They would marry, have three kids, and then divorce, bitterly, at a time when divorce was not really something people were supposed to do.

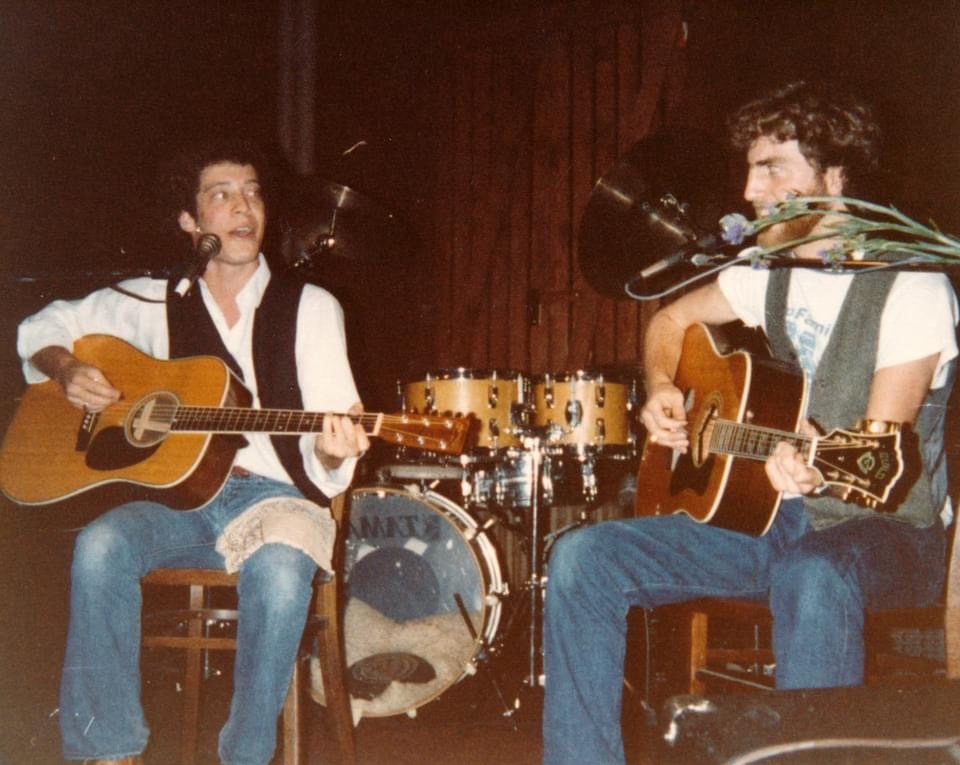

More to the point, though, back in the day, I used to perform regularly. Along with my dear, dear friends Alan Goldberg and Amy Halliday, I was in a band called Free Samples. Three voices, two guitars. Acoustic rock — CSN, Beatles, Paul Simon/Simon and Garfunkel, James Taylor, Bonnie Raitt, Joni Mitchell, Pousette-Dart, etc. We performed several times a semester, usually at the campus coffee house, but also at special events during which we shared the evening with other acoustic bands.

More to the point, though, back in the day, I used to perform regularly. Along with my dear, dear friends Alan Goldberg and Amy Halliday, I was in a band called Free Samples. Three voices, two guitars. Acoustic rock — CSN, Beatles, Paul Simon/Simon and Garfunkel, James Taylor, Bonnie Raitt, Joni Mitchell, Pousette-Dart, etc. We performed several times a semester, usually at the campus coffee house, but also at special events during which we shared the evening with other acoustic bands. As I made clear earlier, I am not the player or singer I used to be, mostly because I don’t work at it as I once did. And so I’m afraid I’ll sound bad. Alan and Dan have played together a lot over the past several years, including live performances and online concerts they gave during the pandemic. They sound great as a twosome and I don’t want to ruin that. They have terrific on-stage rapport, just as Alan and I did back when we were young. I don’t want to get in the way of that, either. And I have overwhelmingly positive memories of my performing days. I don’t want to sully those recollections with a performance now that is subpar. I don’t want to embarrass myself.

As I made clear earlier, I am not the player or singer I used to be, mostly because I don’t work at it as I once did. And so I’m afraid I’ll sound bad. Alan and Dan have played together a lot over the past several years, including live performances and online concerts they gave during the pandemic. They sound great as a twosome and I don’t want to ruin that. They have terrific on-stage rapport, just as Alan and I did back when we were young. I don’t want to get in the way of that, either. And I have overwhelmingly positive memories of my performing days. I don’t want to sully those recollections with a performance now that is subpar. I don’t want to embarrass myself.

Our girls LOVED Sewanee Fourth of July when they were young. We would give them a bit of cash, help them meet up with friends, and then pretty much say goodbye to them for the day. It’s a small, safe, friendly town, and we never worried about them. They always found us eventually, sunburned and sweaty, their faces covered in face-paint, their pockets stuffed with candy that was thrown to kids by the parade participants. We’d go home, have a nap and some dinner, not that any of us was very hungry, and then, after covering ourselves with bug spray, would make our way to the fireworks venue.

Our girls LOVED Sewanee Fourth of July when they were young. We would give them a bit of cash, help them meet up with friends, and then pretty much say goodbye to them for the day. It’s a small, safe, friendly town, and we never worried about them. They always found us eventually, sunburned and sweaty, their faces covered in face-paint, their pockets stuffed with candy that was thrown to kids by the parade participants. We’d go home, have a nap and some dinner, not that any of us was very hungry, and then, after covering ourselves with bug spray, would make our way to the fireworks venue.