Yes, I’ve been quiet for a while. Things are okay. Really. More than okay, actually. But Nancy and I have been hella busy. With travel, with family stuff. But most of all with the big news that is the subject of this post.

This [see the photo above] will soon be our new home. It is in New York’s Hudson Valley, near Albany, on six-plus acres of beautiful land, complete with gardens, fruit trees, and a small pond. More important, it is maybe twenty minutes from my brother and sister-in-law, is equally close to one of my dearest friends and his partner, and is within easy drives of many other friends and family.

This [see the photo above] will soon be our new home. It is in New York’s Hudson Valley, near Albany, on six-plus acres of beautiful land, complete with gardens, fruit trees, and a small pond. More important, it is maybe twenty minutes from my brother and sister-in-law, is equally close to one of my dearest friends and his partner, and is within easy drives of many other friends and family.

We have lived in our current house for nearly twenty-six years, and in our small college town here in on the Cumberland Plateau for more than thirty-two. We raised our girls here, built a home, nurtured successful careers here, made friendships that will last for the rest of our days. Even as we have chafed at the backward, hateful politics of Tennessee, we have reveled in the state’s natural beauty and the friendliness of so many of its people. It is strange and a bit sad to contemplate our imminent departure from this home which we love. (Yeah, we still have to sell the place, but we’re hoping that won’t be too difficult.)

But the rightward tilt of the state, the Tennessee GOP’s fetishistic obsession with gun culture, and the legislature’s unrelenting assault on the rights of women, people of color, and members of the LGBTQ+ community have worsened significantly over the past few years. And, of course, since losing our older daughter, living in the house in which she grew up has become difficult to say the least. It is time for us to leave.

Nancy is deeply grateful to Sewanee: The University of the South for all the opportunities offered to her over the course of her academic career here. She has served in a variety of roles — assistant professor, associate professor, full professor, department chair, associate dean, associate provost, provost, and finally interim Vice-Chancellor of the University. She is the first biology professor to hold the William Henderson Chair in Biology and the first woman in the history of the university to serve as VC. She has loved working for the school.

And I have been so pleased to be part of the Southeast’s speculative fiction community for the past twenty-seven years. I have established wonderful relationships and have been welcomed at literally hundreds of conventions across the region, including many for which I have been designated as a special guest or guest of honor. In 2022, I received the Phoenix Award for Lifetime Achievement from the Southern Fandom Confederation. As I said, I have built a career here, and I will forever be grateful to the fans and colleagues who have become valued friends.

What’s next? What will life be like for us in New York? Well, it’ll be colder. There’ll be more snow. Nancy will be retired, but has plenty of interests and projects to keep herself busy and very, very happy. I intend to keep writing and editing, although I imagine my output will be somewhat lower than it has been in recent years. Then again, who knows. I have no shortage of projects I look forward to taking on. And given how much travel we want to fit in, I’ll need to make some money . . .

We will have more time with family, which will be wonderful. My college friend and I love playing music together, so I am hopeful that music, and even the occasional performance, will become a larger part of my life.

And we will continue to heal, to rely upon each other, and upon Erin, for love, support, hope, and laughter. It won’t be perfect, of course. Nothing ever is. But it is our next adventure, and we’re looking forward to it. I promise that we’ll keep you informed. In a social media sense, I’m not going anywhere.

Enjoy the rest of your week.

More to the point, though, back in the day, I used to perform regularly. Along with my dear, dear friends Alan Goldberg and Amy Halliday, I was in a band called Free Samples. Three voices, two guitars. Acoustic rock — CSN, Beatles, Paul Simon/Simon and Garfunkel, James Taylor, Bonnie Raitt, Joni Mitchell, Pousette-Dart, etc. We performed several times a semester, usually at the campus coffee house, but also at special events during which we shared the evening with other acoustic bands.

More to the point, though, back in the day, I used to perform regularly. Along with my dear, dear friends Alan Goldberg and Amy Halliday, I was in a band called Free Samples. Three voices, two guitars. Acoustic rock — CSN, Beatles, Paul Simon/Simon and Garfunkel, James Taylor, Bonnie Raitt, Joni Mitchell, Pousette-Dart, etc. We performed several times a semester, usually at the campus coffee house, but also at special events during which we shared the evening with other acoustic bands. As I made clear earlier, I am not the player or singer I used to be, mostly because I don’t work at it as I once did. And so I’m afraid I’ll sound bad. Alan and Dan have played together a lot over the past several years, including live performances and online concerts they gave during the pandemic. They sound great as a twosome and I don’t want to ruin that. They have terrific on-stage rapport, just as Alan and I did back when we were young. I don’t want to get in the way of that, either. And I have overwhelmingly positive memories of my performing days. I don’t want to sully those recollections with a performance now that is subpar. I don’t want to embarrass myself.

As I made clear earlier, I am not the player or singer I used to be, mostly because I don’t work at it as I once did. And so I’m afraid I’ll sound bad. Alan and Dan have played together a lot over the past several years, including live performances and online concerts they gave during the pandemic. They sound great as a twosome and I don’t want to ruin that. They have terrific on-stage rapport, just as Alan and I did back when we were young. I don’t want to get in the way of that, either. And I have overwhelmingly positive memories of my performing days. I don’t want to sully those recollections with a performance now that is subpar. I don’t want to embarrass myself.

Our girls LOVED Sewanee Fourth of July when they were young. We would give them a bit of cash, help them meet up with friends, and then pretty much say goodbye to them for the day. It’s a small, safe, friendly town, and we never worried about them. They always found us eventually, sunburned and sweaty, their faces covered in face-paint, their pockets stuffed with candy that was thrown to kids by the parade participants. We’d go home, have a nap and some dinner, not that any of us was very hungry, and then, after covering ourselves with bug spray, would make our way to the fireworks venue.

Our girls LOVED Sewanee Fourth of July when they were young. We would give them a bit of cash, help them meet up with friends, and then pretty much say goodbye to them for the day. It’s a small, safe, friendly town, and we never worried about them. They always found us eventually, sunburned and sweaty, their faces covered in face-paint, their pockets stuffed with candy that was thrown to kids by the parade participants. We’d go home, have a nap and some dinner, not that any of us was very hungry, and then, after covering ourselves with bug spray, would make our way to the fireworks venue. Somewhere along the way, as her battle went on, Alex decided she wanted to have the image of those blooms tattooed on her arm. She turned to a friend from NYU who had become an accomplished tattoo artist. This friend, Ally Zhou, specializes in fine line work, and was the ideal person to render the precise details of the dried bouquet. The result was a gorgeous tattoo that Alex bore proudly for the rest of her too-short life.

Somewhere along the way, as her battle went on, Alex decided she wanted to have the image of those blooms tattooed on her arm. She turned to a friend from NYU who had become an accomplished tattoo artist. This friend, Ally Zhou, specializes in fine line work, and was the ideal person to render the precise details of the dried bouquet. The result was a gorgeous tattoo that Alex bore proudly for the rest of her too-short life. I know there are many of you reading this for whom a small tattoo is no big deal. You have sleeves or extensive back pieces or whatever. I think that’s great. But as I say, this was something Nancy and I had never intended to do. It felt momentous, like a ritual of sorts, a way of alchemizing our grief into something physical and shared and public, something that links us to one another and to Alex. I love my new tattoo, for what it means as well as for how it looks.

I know there are many of you reading this for whom a small tattoo is no big deal. You have sleeves or extensive back pieces or whatever. I think that’s great. But as I say, this was something Nancy and I had never intended to do. It felt momentous, like a ritual of sorts, a way of alchemizing our grief into something physical and shared and public, something that links us to one another and to Alex. I love my new tattoo, for what it means as well as for how it looks. And in part, this is the fault of professionals like me, who talk about our work habits and, perhaps, create unrealistic expectations that writers with less experience then apply to themselves. I write full time. I demand of myself that I write 2,000 words per day. I am asked often how long it takes me to write a book, and the honest answer is that it takes me about three months, which is pretty quick, I know. Writers who are at the outsets of their careers should not necessarily expect to do the same.

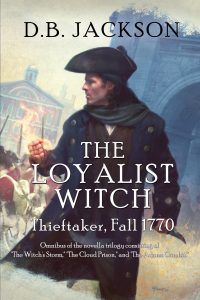

And in part, this is the fault of professionals like me, who talk about our work habits and, perhaps, create unrealistic expectations that writers with less experience then apply to themselves. I write full time. I demand of myself that I write 2,000 words per day. I am asked often how long it takes me to write a book, and the honest answer is that it takes me about three months, which is pretty quick, I know. Writers who are at the outsets of their careers should not necessarily expect to do the same. We’ll begin with the assumption that the book we’re writing will come in at around 100,000 words, which is the approximate length of most of the Thieftaker books, the Chalice War books, and the Fearsson books. Epic fantasies tend to be somewhat longer; YAs tend to be shorter. But 100K is a good middle ground.

We’ll begin with the assumption that the book we’re writing will come in at around 100,000 words, which is the approximate length of most of the Thieftaker books, the Chalice War books, and the Fearsson books. Epic fantasies tend to be somewhat longer; YAs tend to be shorter. But 100K is a good middle ground. Feeling more ambitious? Say we can write for ninety minutes each weekday, and can manage to average 500 words a day, while taking our weekends off to recharge. Well, now we’re writing 2,500 words per week, and that novel will be done in less than nine months. Willing to write on weekends, too? Now we’re down to seven months.

Feeling more ambitious? Say we can write for ninety minutes each weekday, and can manage to average 500 words a day, while taking our weekends off to recharge. Well, now we’re writing 2,500 words per week, and that novel will be done in less than nine months. Willing to write on weekends, too? Now we’re down to seven months.