How are you holding up?

No, really. I’m asking. I’m asking you, and I’ve been asking myself over the past week or so.

This is a remarkable time we’re living through. Obviously, I don’t mean remarkable as in “This is great!” But remarkable as in, “We’ll be talking about this, and recovering from this, for years to come.” It is fraught and troubling and disorienting and challenging and, well, insert your own adjective here. I tend to be a news junkie; I rarely tune out the world. But I know many people who do, who prefer to keep politics and social issues in the background except for those moments – Election Day, for instance – when they feel they need to tune in.

Right now, though, we are living the news on a daily basis. There is no escaping it. There seems to be no distance between the world and our lives. There’s a direct line from those Covid maps on CNN and MSNBC and the cloth masks we put on to shop or go to the bank. Nor does it help that the Administration, which has failed utterly to develop a strategy for combatting the pandemic is, nevertheless, more than happy to exploit it in the most cynical ways possible for political gain.

But I have addressed those issues in past Monday Musings, and I’m sure I’ll do so again in future ones. Today, I’m focused more on the personal costs.

How am I doing? Thanks for asking. As I say, this is something I’ve been asking myself recently.

I’ll start with this: In all ways that matter I’m fine. My family and I have been fortunate so far and have avoided the virus. I am also fortunate in that I’m self-employed and have resources to fall back on even as the publishing industry has ground to a halt. I’m white, upper-middle class, and I live in a relatively isolated area. For those who are non-white, who lack financial security, who live in cities or crowded suburbs, all of this is far, far worse.

That said, I find that I’m struggling. I miss my kids, who I haven’t been able to see in months because of Covid concerns. Our older daughter is supposed to come pick up our old car tomorrow – our first time seeing her since December – but even this visit will be brief (just the evening) and distanced. Our other daughter we haven’t seen since March, and even that is far too long. I also miss my brother and his family, who we likely would have seen at some point this summer or fall.

I honestly don’t mind masking at all, but I miss seeing people – friends and even strangers. I miss going to a restaurant or bar. I miss travel. Problems of privilege, I know, but I’m being honest here. I really miss conventions – hanging out with friends, talking shop with fellow writers, interacting with fans. This past weekend, I was supposed to be in Calgary for a writing festival. A couple of weeks from now I am supposed to be in Atlanta for DragonCon, a highlight of my professional year. I work alone, and most of the time I enjoy delving into my imagination each day. That’s my job. These days, though, it feels particularly lonely.

I walk every day, but I miss my more vigorous workouts at the gym. And because I’m dealing with an unrelated medical issue that is affecting my shoulder, I have had to cut way back on my home workouts as well, which I find deeply frustrating, even depressing.

Mostly, I am weary of thinking about the pandemic, about the politics of the pandemic, about the logistical gymnastics we all have to go through for even the most mundane of errands because of the pandemic. This is exhausting – and way more so for those who have compromised immune systems and/or belong to at-risk groups. It would be terrifying if we had no health insurance, or lacked faith in the medical professionals in our area. Again, I recognize that I am very fortunate.

(And this, by the way, is what makes the Trump Administration’s mail-system machinations and its blindly foolish insistence on opening schools — just to name two of its worst offenses — so insidious. We are, all of us, dealing with heightened emotions, tensions, apprehensions. I can hardly imagine being the parent of school-aged children and, on top of everything else, worrying now about sending them to school.)

I get mad at myself when I am less productive in my work than I would like to be, or when I let everyday chores slide. The truth is, I should be cutting myself a bit of slack. We all should. The stress induced by this particular moment in history in unlike anything I’ve experienced in my lifetime. To my mind, it is rivaled only by the aftermath of 9/11.

I am, in the end, tired of it all. And I’m tired of whining about it. But for all of us who care, who take the threat as seriously as it merits, this is hard. I have no answers, no wisdom to dispense. As I said, I’m struggling, too. I do believe life will get better. I won’t say I expect us to go back to the old normal, but I expect the new normal – whatever that looks like – to be far more enjoyable than this.

Until then, please know that I am wishing all of you good health, simple joys, moments of peace and laughter and love. Stay well, be safe, take good care of one another. We will get through this.

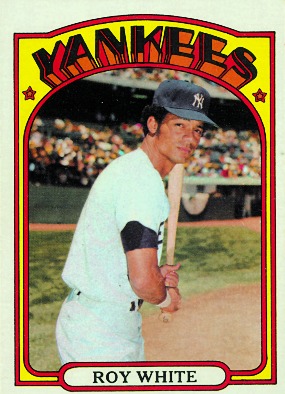

The Yankees were playing the Minnesota Twins, a powerful team lead by perennial all-star Tony Oliva and future Hall of Fame slugger Harmon Killebrew. The Twins jumped out to an early lead, gave a run back, but still led 2-1 in the fifth inning, the second inning of Mantle’s stint as coach. The Yankees managed to load the bases and, with two outs, their left fielder, a guy named Roy White, stepped to the plate.

The Yankees were playing the Minnesota Twins, a powerful team lead by perennial all-star Tony Oliva and future Hall of Fame slugger Harmon Killebrew. The Twins jumped out to an early lead, gave a run back, but still led 2-1 in the fifth inning, the second inning of Mantle’s stint as coach. The Yankees managed to load the bases and, with two outs, their left fielder, a guy named Roy White, stepped to the plate. This past Friday our little college town had a peaceful protest march followed by a rally on the college quad. It was a terrific event: somber, but also uplifting. Several people spoke, including my wife, who is provost of the university. Most of the speakers were Black; Nancy is not. And her message was directed at the many White allies who were in attendance. Showing up is great, she said. But it’s not enough. We who consider ourselves allies of those fighting for racial justice, but who also carry enormous privilege, have to challenge ourselves to act, to fight every day for a better world. And she, in turn, challenged us. Think of things you can do. Commit yourselves.

This past Friday our little college town had a peaceful protest march followed by a rally on the college quad. It was a terrific event: somber, but also uplifting. Several people spoke, including my wife, who is provost of the university. Most of the speakers were Black; Nancy is not. And her message was directed at the many White allies who were in attendance. Showing up is great, she said. But it’s not enough. We who consider ourselves allies of those fighting for racial justice, but who also carry enormous privilege, have to challenge ourselves to act, to fight every day for a better world. And she, in turn, challenged us. Think of things you can do. Commit yourselves.