Okay, I am tired of Covid posts, of contemplating the meaning of life in the time of plague and all that. Today’s Musings are of an entirely frivolous sort. I have been listening to A LOT of music. Oldish music. Boomer music. Dad music. The music I have listened to and loved since I was a kid being turned on to 60s and 70s rock by my older siblings. (I wrote about this in the context of another music post earlier this year.)

And because I’m bored, and having trouble focusing on the work at hand, and also a huge fan of the movie High Fidelity, I started making lists in my head. What sort of lists? I am SO glad you asked….

[And before I go on, this is my list of MY favorites. I know they may not be “the best.” I’m sure that we could survey one hundred of you and wind up with a hundred different answers for all of these. I did this for fun, and because I thought you might find it entertaining. I am not looking for a fight and will not engage in arguments about any of this. Okay?]

My Favorite Musical Performer: This is a no-brainer, and it is a sentimental choice. My very first real album (not something put out by Hanna-Barbera) was James Taylor’s Sweet Baby James, which I was given when I was seven years old. Ever since, James Taylor has been my favorite, the artist I go to when I need cheering up, when I seek solace or comfort. His music has literally been the soundtrack of my life; his various albums are signposts that help me date certain key moments of my personal history. I know he’s not the best musician or the best songwriter, but he is the one I love most. Also, he and I share a birthday. For what that’s worth.

My Favorite Band: Little Feat. A little bit rock, a little bit country, with elements of funk and R and B and Creole thrown in. I was turned on to Little Feat by my oldest brother, Bill, who was my guru for all things Rock ‘n Roll. Their live album, Waiting for Columbus, is, in my view, the greatest live album ever made. And I say that as a huge fan of the Allman Brothers’ Live at Fillmore East. Sacrilege, I know. But this is my blog. So there. For a sample of their sound listen to the live version of “Dixie Chicken” or any version of “Rock ‘n Roll Doctor.”

My Favorite Songwriter: There are a lot of wonderful songwriters out there, including James, Jackson Browne, Dylan, Lennon and McCartney, and, the one who was very nearly my top choice, Paul Simon. Among newer artists I think Adam Duritz and, yes, Taylor Swift are both remarkable writers. But to my mind the finest songwriter of the last half century is Joni Mitchell. And I think if she was a guy, it wouldn’t be a controversial choice. Her lyrics are simply brilliant – emotional, unexpected, evocative. Listen to “A Case of You” or “Song For Sharon.” I know some don’t like her voice. Sometimes I don’t either. This is about the songs and lyrics themselves.

My Favorite Musicians: Okay, this is a tricky one – I’m kind of thinking about this the way I might an all-star team: putting together my favorites by instrument. I’m not necessarily looking at creating the perfect band. Some of my choices don’t go together so well. But… well… this is my game and these are the rules by which I’m playing.

Lead Vocals, Male: So many great voices to choose from – Roger Daltry, Bob Seeger, David Crosby (a personal favorite). But I think my favorite guy’s rock voice might be Phil Collins. Honorable mention: Adam Duritz of Counting Crows fame. And Michael McDonald from his Doobie Brother days.

Lead Vocals, Female: Again, so many great voices. I was never a Heart fan, but Ann and Nancy Wilson could sing. That said, I have to go with Melissa Etheridge. LOVE her voice. Bluesy, gravelly, powerful. She’s also a remarkable songwriter and has been a courageous voice for social justice. And I could listen to her sing all day long. Honorable mention: Bonnie Raitt, Christine McVie, and Susan Tedeschi.

Lead Guitar: David Gilmour of Pink Floyd. His solos have a blend of edginess and elegance that I just love. Listen to the guitar work on “Comfortably Numb.” Mind-blowing. Honorable mention to about a thousand people, among them: Dickey Betts, Stephen Stills, Patrick Simmons, Jerry Garcia, Mick Taylor as well as the giants, Clapton and Hendrix.

Rhythm Guitar: Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones. Yeah, I know he also plays lead, but I think that while he is a very good lead guitarist, he is a masterful rhythm guitarist. That’s just me, but it’s how I feel. Honorable Mention: Bobby Weir.

Slide Guitar: I include this because it’s probably my favorite instrument to listen to. And it’s a chance for me to mention Lowell George, the creative force behind Little Feat, and the best slide guitarist I’ve ever heard. Honorable mention: Bonnie Raitt, Duane Allman, Jon Pousette-Dart, and Derek Trucks.

Keyboards: I will admit that I know far less about keyboards than I ought to. I love Elton John, and so does my wife. But I’m not sure how he fits with this list. Among my favorites are also two from the same band, which is a little unusual. Gregg Allman played organ and piano for the Allman Brothers Band and was very good at both. And Chuck Leavell’s piano solo on the song “Jessica” is one of the most joyous passages of rock ever recorded. So they will share top billing for me, with honorable mention going to Billy Payne and Billy Powell.

Bass: “Do not be deceived by nor take lightly this bit of musicianship that one describes simply as ‘bass.’” Kenny Gradney of Little Feat. Just a remarkably expressive and creative bass player. Honorable mention: Tina Weymouth and Phil Lesh.

And finally Drums: This one, to my mind, is not even close. There are drummers, and then there is Keith Moon, of The Who. His work was mesmerizing, surprising, powerful – just terrific stuff. Honorable mention to Steve Gadd and Charlie Watts.

Anyway, hope you enjoyed this. Maybe next week I’ll do movies and movie stars…

Have a great week!

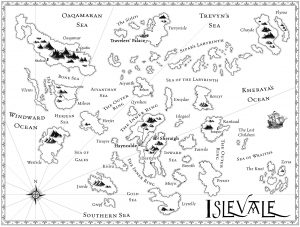

And then I just let my imagination run wild. At first I let my hand wander over the page, creating the broad outlines of my world. Sometimes I have to start over a couple of times before I come up with a design I like. But generally, I find that the less I impose pre-conceived notions on my world, the more successful my initial efforts. I draw land masses, taking care to make my shorelines realistically intricate. (Take a look at a map of the real world. Even seemingly “smooth” coastlines are actually filled with inlets, coves, islands, etc.) I put in rivers and lakes. I locate my mountain ranges, deserts, wetlands, etc.

And then I just let my imagination run wild. At first I let my hand wander over the page, creating the broad outlines of my world. Sometimes I have to start over a couple of times before I come up with a design I like. But generally, I find that the less I impose pre-conceived notions on my world, the more successful my initial efforts. I draw land masses, taking care to make my shorelines realistically intricate. (Take a look at a map of the real world. Even seemingly “smooth” coastlines are actually filled with inlets, coves, islands, etc.) I put in rivers and lakes. I locate my mountain ranges, deserts, wetlands, etc.

Last week, I went on a hike and took a bunch of photographs (if you haven’t already,

Last week, I went on a hike and took a bunch of photographs (if you haven’t already,