Trust your reader.

Trust your reader.

This is editor speak for “trust yourself.” It is something I say often to many of the writers I edit.

But what does it mean?

I have had my own lesson in “trust your reader” in recent days as I have begun the long, arduous task of editing for reissue the five volumes of my Winds of the Forelands epic fantasy series, originally published by Tor Books back in the early 2000s, when I was still a relative newbie. My editor at Tor used to tell me all the time to trust my readers, and so I assumed — naïvely, it would seem — that back in the day he and I had caught all the instances where I didn’t trust my reader. But no. It seems there were so many of these moments, that he had to engage in a sort of editorial triage, catching only the most egregious and leaving the rest.

Yes, I know. I still haven’t defined the phrase.

As I say, “trust your reader” is essentially the same as “trust yourself.” And editors use it to point out all those places where we writers tell our readers stuff that they really don’t have to be told. Writers spend a lot of time setting stuff up — arranging our plot points just so in order to steer our narratives to that grand climax we have planned; building character backgrounds and arcs of character development that carry our heroes from who they are when the story begins to who we want them to be when the story ends; building histories and magic systems and other intricacies into our world so that all the storylines and character arcs fit with the setting we have crafted with such care.

As I say, “trust your reader” is essentially the same as “trust yourself.” And editors use it to point out all those places where we writers tell our readers stuff that they really don’t have to be told. Writers spend a lot of time setting stuff up — arranging our plot points just so in order to steer our narratives to that grand climax we have planned; building character backgrounds and arcs of character development that carry our heroes from who they are when the story begins to who we want them to be when the story ends; building histories and magic systems and other intricacies into our world so that all the storylines and character arcs fit with the setting we have crafted with such care.

And because we work so hard on all this stuff (and other narrative elements I haven’t even mentioned) we want to be absolutely certain that our readers get it all. We don’t want them to miss a thing, because then all our Great Work will be for naught. Because maybe, just maybe, if they don’t get it all, then our Wonderful Plot might not come across as quite so wonderful, and our Deep Characters might not come across as quite so deep, and our Spectacular Worlds might not feel quite so spectacular.

And because we work so hard on all this stuff (and other narrative elements I haven’t even mentioned) we want to be absolutely certain that our readers get it all. We don’t want them to miss a thing, because then all our Great Work will be for naught. Because maybe, just maybe, if they don’t get it all, then our Wonderful Plot might not come across as quite so wonderful, and our Deep Characters might not come across as quite so deep, and our Spectacular Worlds might not feel quite so spectacular.

And that would be A Tragedy.

Okay, yes, I’m making light, poking fun at myself and my fellow writers. But fears such as these really do lie at the heart of most “trust your reader” moments. And so we fill our stories with unnecessary explanations, with redundancies that are intended to remind, but that wind up serving no purpose, with statements of the obvious and the already-known that serve only to clutter our prose and our storytelling.

Okay, yes, I’m making light, poking fun at myself and my fellow writers. But fears such as these really do lie at the heart of most “trust your reader” moments. And so we fill our stories with unnecessary explanations, with redundancies that are intended to remind, but that wind up serving no purpose, with statements of the obvious and the already-known that serve only to clutter our prose and our storytelling.

The first few hundred pages of Rules of Ascension, the first volume of Winds of the Forelands, is filled to bursting with unnecessary passages of this sort. I explain things again and again. I remind my readers of key points in scenes that took place just a dozen or so pages back. I make absolutely certain that my readers are well versed in every crucial element (“crucial” as determined by me, of course) in my world building and character backgrounds.

As a result, the first volume of the series was originally 220,000 words long. Yes, that’s right. Book II was about 215,000, and the later volumes were each about 160,000. They are big freakin’ books. Now, to be clear, there are other things that make them too wordy, and I’m fixing those as well. And the fact is, these are big stories and even after I have edited them, the first book will still weigh in at well over 200,000 words. My point is, they are longer than they need to be. They are cluttered with stuff my readers don’t need, and all that stuff gets in the way of the many, many good things I have done with my characters and setting and plot and prose.

As a result, the first volume of the series was originally 220,000 words long. Yes, that’s right. Book II was about 215,000, and the later volumes were each about 160,000. They are big freakin’ books. Now, to be clear, there are other things that make them too wordy, and I’m fixing those as well. And the fact is, these are big stories and even after I have edited them, the first book will still weigh in at well over 200,000 words. My point is, they are longer than they need to be. They are cluttered with stuff my readers don’t need, and all that stuff gets in the way of the many, many good things I have done with my characters and setting and plot and prose.

I have always been proud of these books. I remain so even as I work through this process. People have read and enjoyed all five volumes as originally written despite the “trust your reader” moments. I actually think most readers pass over those redundant, unnecessary passages without really noticing them. They are not horrible or glaring (except to me); they’re just annoying. They are rookie mistakes, and so I find them embarrassing, and I want to eliminate as many as possible before reissuing the books.

But our goal as writers ought to be to produce the best stories we can write, with the clearest, most concise narratives and the cleanest, most readable prose. “Trust your reader” moments are a hindrance — one among many — to the achievement of that goal, and so we should be aware of the tendency and work to eliminate these unnecessary passages from our writing.

Mostly, we should remember the translation — “trust your reader” means “trust yourself.” Chances are we have laid our groundwork effectively, establishing our worlds, developing our characters, setting up our plot points. If we haven’t, a good editor will tell us so and will recommend places where we can clarify matters a bit.

So, remember that less is usually more, that showing is almost always better than telling, that most times when we stop to explain stuff we rob our stories of momentum.

And most of all, remember to trust yourself. You’ve earned it.

Keep writing.

The bias against genre fiction (fantasy, science fiction, mystery, Westerns, romance, etc.) among those who consider themselves devotees of “true” literature, is something I have encountered again and again throughout my career. Not surprisingly, I don’t believe it has any basis in reality. Fantasy (to address my speciality) like literary fiction, runs the gamut in terms of quality. One can find in all literary fields examples of brilliance and also of mediocrity. No genre has a monopoly on either. I write fantasy because I enjoy it, because I love to imbue my stories with magic, with phenomena I don’t encounter in my everyday life. I wasn’t shunted to this genre because I wasn’t good enough to write the other stuff. I don’t hide in my genre because I fear I can’t cut it in the world of “real” literature.

The bias against genre fiction (fantasy, science fiction, mystery, Westerns, romance, etc.) among those who consider themselves devotees of “true” literature, is something I have encountered again and again throughout my career. Not surprisingly, I don’t believe it has any basis in reality. Fantasy (to address my speciality) like literary fiction, runs the gamut in terms of quality. One can find in all literary fields examples of brilliance and also of mediocrity. No genre has a monopoly on either. I write fantasy because I enjoy it, because I love to imbue my stories with magic, with phenomena I don’t encounter in my everyday life. I wasn’t shunted to this genre because I wasn’t good enough to write the other stuff. I don’t hide in my genre because I fear I can’t cut it in the world of “real” literature. It’s not enough to create my worlds and magic systems. I have to explain them to my readers in a manner that is entirely natural and unobtrusive. And — my own preference — I also have to complete my stories and my character arcs in ways that utilize my fantasy elements without allowing them to take over my story telling. My heroes may possess magic, but in the end, I will always choose to have them prevail by drawing upon their native human qualities — their courage and resolve, their intelligence and creativity, their devotion to the people and places they love. Magic sets them apart and makes them interesting. It is often the hook the draws readers to my books. But those human attributes — those are the ones my real-world readers relate to. They form the bond between my readers and my characters. And so if those are the qualities that allow my characters to prevail in the end, then their triumphs will feel more personal and rewarding to my readers. It is the simplest sort of literary math.

It’s not enough to create my worlds and magic systems. I have to explain them to my readers in a manner that is entirely natural and unobtrusive. And — my own preference — I also have to complete my stories and my character arcs in ways that utilize my fantasy elements without allowing them to take over my story telling. My heroes may possess magic, but in the end, I will always choose to have them prevail by drawing upon their native human qualities — their courage and resolve, their intelligence and creativity, their devotion to the people and places they love. Magic sets them apart and makes them interesting. It is often the hook the draws readers to my books. But those human attributes — those are the ones my real-world readers relate to. They form the bond between my readers and my characters. And so if those are the qualities that allow my characters to prevail in the end, then their triumphs will feel more personal and rewarding to my readers. It is the simplest sort of literary math. I discussed the Thieftaker books in last week’s post, and I mentioned how my love of U.S. history steered me toward setting the series in pre-Revolutionary Boston. But I failed to mention then that upon deciding to set the books in 1760s Boston, I then had to dive into literally months of research. Sure, I had read colonial era history for my Ph.D. exams, but I had never looked at the period the way I would need to in order to use it as a setting for a novel, much less several novels and more than a dozen pieces of short fiction. Ironically, as a fiction author I needed far more basic factual information about the city, about the time period, about the historical figures who would appear in my narratives, than I ever did as a doctoral candidate.

I discussed the Thieftaker books in last week’s post, and I mentioned how my love of U.S. history steered me toward setting the series in pre-Revolutionary Boston. But I failed to mention then that upon deciding to set the books in 1760s Boston, I then had to dive into literally months of research. Sure, I had read colonial era history for my Ph.D. exams, but I had never looked at the period the way I would need to in order to use it as a setting for a novel, much less several novels and more than a dozen pieces of short fiction. Ironically, as a fiction author I needed far more basic factual information about the city, about the time period, about the historical figures who would appear in my narratives, than I ever did as a doctoral candidate. The same is true of the worlds I build from scratch for my novels. My most recent foray into wholesale world building was the prep work I did for my Islevale Cycle, the time travel/epic fantasy books I wrote a few years ago. As with my Thieftaker research, my world building for the Islevale trilogy consumed months. I began (as I do with my research) with a series of questions about the world, things I knew I had to work out before I could write the books. How did the various magicks work? What were the relationships among the various island nations? Where did my characters fit into these dynamics? Etc.

The same is true of the worlds I build from scratch for my novels. My most recent foray into wholesale world building was the prep work I did for my Islevale Cycle, the time travel/epic fantasy books I wrote a few years ago. As with my Thieftaker research, my world building for the Islevale trilogy consumed months. I began (as I do with my research) with a series of questions about the world, things I knew I had to work out before I could write the books. How did the various magicks work? What were the relationships among the various island nations? Where did my characters fit into these dynamics? Etc. As many of you know, my first series, the LonTobyn Chronicle, had as its narrative core, a magic system in which mages formed psychic, magical bonds with birds of prey: hawks, owls, eagles. To this day, fans of the series mention those relationships between mages and their avian familiars, as the element of the books they enjoyed most.

As many of you know, my first series, the LonTobyn Chronicle, had as its narrative core, a magic system in which mages formed psychic, magical bonds with birds of prey: hawks, owls, eagles. To this day, fans of the series mention those relationships between mages and their avian familiars, as the element of the books they enjoyed most. This past weekend I gave a talk on world building for the Futurescapes Writers’ Workshop. It was a lengthy talk, and I’m not going to repeat all of it here. But I did want to focus on one element of the topic, because I think it’s something writers of fantasy, of historical fiction, of science fiction, and of other sub-categories of speculative fiction lose sight of now and again.

This past weekend I gave a talk on world building for the Futurescapes Writers’ Workshop. It was a lengthy talk, and I’m not going to repeat all of it here. But I did want to focus on one element of the topic, because I think it’s something writers of fantasy, of historical fiction, of science fiction, and of other sub-categories of speculative fiction lose sight of now and again.

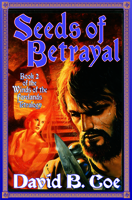

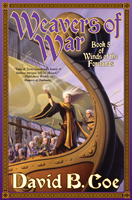

For the Winds of the Forelands series (Rules of Ascension, Seeds of Betrayal, Bonds of Vengeance, Shapers of Darkness, Weavers of War) , I created what is without a doubt the most complex “calendar” I’ve ever undertaken for any project. For those of you not familiar with the world, I’ll give a very brief description. The world has two moons, Ilias and Panya, the Lovers, who chase each other across the sky. Each turn (month) has one night when both moons are full (the Night of Two Moons) and one night when both moons are dark (Pitch Night). Each turn is also named for a god or goddess, and so each Night of Two Moons and each Pitch Night has a special meaning.

For the Winds of the Forelands series (Rules of Ascension, Seeds of Betrayal, Bonds of Vengeance, Shapers of Darkness, Weavers of War) , I created what is without a doubt the most complex “calendar” I’ve ever undertaken for any project. For those of you not familiar with the world, I’ll give a very brief description. The world has two moons, Ilias and Panya, the Lovers, who chase each other across the sky. Each turn (month) has one night when both moons are full (the Night of Two Moons) and one night when both moons are dark (Pitch Night). Each turn is also named for a god or goddess, and so each Night of Two Moons and each Pitch Night has a special meaning.