Two years ago at this time, we were just starting to hear reports of a strange new disease first discovered in the Wuhan Province of China. We didn’t know much about it, and while doctors in China expressed concern about what they were seeing, most of us didn’t think much of it. China, I remember thinking, is a long way away. Whatever this illness is, it’s not likely to have a huge impact on my life.

The hubris. The foolishness. The ignorance. The innocence.

This Sunday morning, as I began thinking about this week’s post, I went back and read some of the Monday Musings I wrote in 2020, when we as a society were first coming to grips with Covid and its implications for our lives and our world. I returned to the topic again and again that year, lamenting the previous Administration’s bumbling response to the pandemic, and trying to make sense in real time of the changes being imposed upon us by something we didn’t yet fully understand.

As I read yesterday, some of what I found in those posts from 2020 struck me as eerily familiar. Almost from the very beginning a certain, too-large segment of our society refused to take any steps to combat the spread of the virus because the actions in question conflicted with their concept of “personal freedom,” of “liberty.” At the time this mostly meant objecting to mask-wearing, to restrictions on large social gatherings, to business closings that prevented people from eating out and going to sports events and shopping in malls.

Today, we fight many of the same battles, and, of course, we struggle with the added social conflicts over vaccines and vaccine mandates.

We worried then, as we do now, about school closures and remote learning, and their impact on children and families. We saw fatigue and desperation and grief battering health care workers, and we worried about the long-term impact their ordeal would have on our entire medical system. And we saw Covid and the public battles over how to deal with it being politicized, deepening the fracture lines in a nation already bitterly divided by politics and social strife.

In too many ways, nothing has changed. And in other ways, things have only gotten worse.

At the time, we believed children were somehow immune to Covid. We have since learned, tragically, how mistaken we were.

Early on, the CDC was projecting deaths from Covid in the U.S. would exceed 100,000 and might reach as high as a quarter of a million. The number of cases of the illness, we were told, might reach into the millions.

The innocence. The ignorance . . . .

Currently, as we weather the third major wave of Covid, our nation’s death toll stands at approximately 835,000. The total number of cases stands at about 60,000,000.

I wrote in one of my earliest 2020 posts about how I remained hopeful that when the pandemic had run its course, we would return to something approaching the normal life we once had known. I was thinking a couple of months, maybe six, maybe a year. Two years on, and I no longer have any illusions about “normal” and what that means. By midsummer in 2020, I understood how naïve I had been. Normal, as we once conceived it, was already gone. We now live in a Covid world. I expect it will forever be a part of our health-scape. Like flu. Like AIDS.

Pretty grim, right?

Except it’s not. Yes, I know, as often as not (or more) my optimistic takes on things turn out to be off base. And if this is another instance, so be it.

But we as a society have learned to live with flu. We get shots, and though the flu vaccines are imperfect year to year, because they are based on health professionals’ best guess as to what the coming season’s flu strain will look like, they generally perform quite well. AIDS was once a death sentence. It’s not anymore.

Over 245 million Americans have received at least one dose of a Covid vaccine. Over 206 million are fully vaccinated. The numbers are growing. We must remain committed to fighting the wacky conspiracy theories and the misinformation, so that we can vaccinate millions more in the coming months. But compared to where we were a year ago, we are safer today because of the vaccines. Covid today is hitting hardest in counties with the lowest vaccination rates. Those who are getting sickest from Covid are those who haven’t had the shots. The vaccines work.

Omicron is hitting the country — and the world — hard right now. But it is demonstrably milder than the original strain and than Delta. My wife, who is a Stanford-trained biologist, tells me this is often the pattern with illnesses. They grow more contagious over time, but also less virulent. And there is an evolutionary explanation for this. The contagion grows, because like all living creatures viruses are driven to propagate, to ensure their own continued existence. And the virulence declines because a virus that kills its host has less chance of surviving and reproducing.

Moreover, while many of the problems we encountered with Covid in the earliest days of the pandemic have persisted over these two years, others have not. I wrote early on that I was so distracted by the pandemic and the accompanying social disruptions that I could barely work. I was desperate for normal interactions, for anything that felt familiar and safe. I had trouble remembering what day of the week it was.

As the pandemic has gone on, though, I have adjusted. I can keep track of the days better. I work every day at a pace very much like that which I maintained pre-pandemic. I don’t like Zoom very much, but I use it a lot and keep connected that way. I have attended many virtual conventions, and have taught workshops remotely. And I have gotten used to wearing my mask, to being with friends in open-air settings, to shopping online rather than in person, to cooking every night with Nancy rather than eating out once a week, or once every couple of weeks.

Is any of this ideal? Of course not. But neither is it such a hardship that I can’t cope. I still do believe we will come to some new way of living that feels closer to the old normal than where we are now. I no longer try to guess when that might happen. Because I can’t know. And because I am not as desperate for it as I was a couple of years ago.

I understand fully that I am privileged in this respect. For too many, the disruptions of the pandemic have been utterly devastating and have done permanent damage — physically, emotionally, economically. And I hope that as a society we will show compassion to those who have suffered most, and will help them rebuild their lives.

My point today, though, is that I believe this will be possible. Two years on, too much is the same. Too much has gotten worse. And yet so many of us have adjusted and are adjusting. It may not seem like it much of the time, but we are already building that “next normal.”

Have a great week.

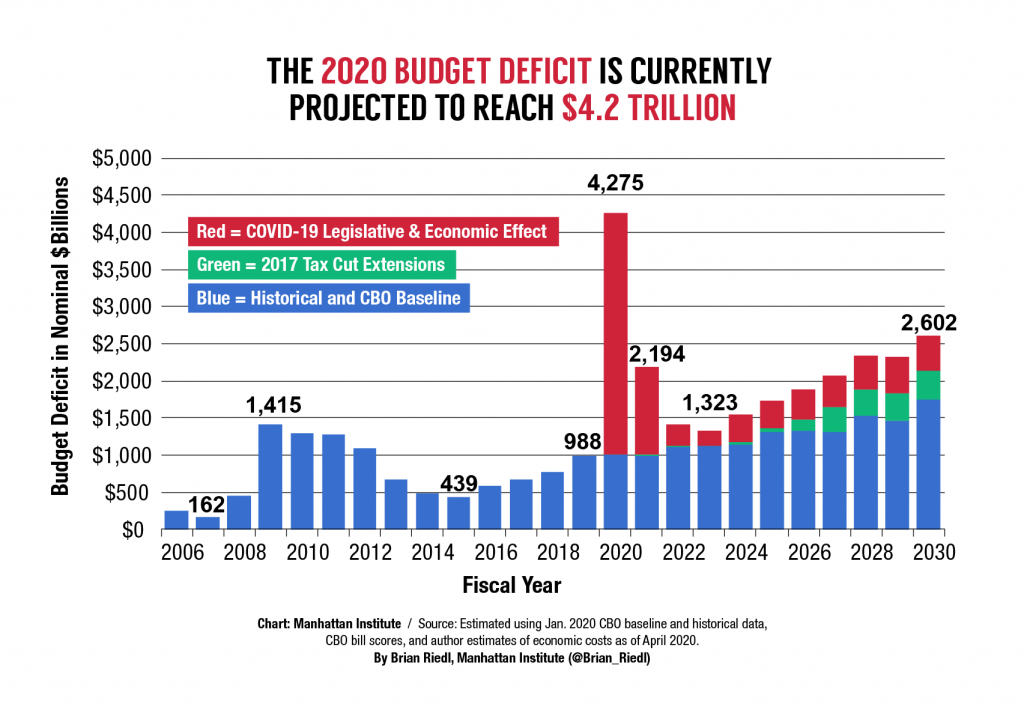

And one more point I would like to make. Interest on the national debt currently gobbles up 8 cents out of every tax dollar. The budget deficit for 2020 was $3.7 TRILLION (slightly less than the chart above projects — I included the chart for the trend line). Even before the pandemic hit, necessitating emergency spending, the Trump tax cuts had driven projected deficits way up over where they were by the end of the Obama Administration. Some will try to tell you that those tax cuts simply returned money to the pockets of Americans. Bull. Every dollar that Donald Trump added to the deficit increased that interest expenditure I just mentioned and forced the rest to pay more. By skewing his cuts to the wealthiest among us, he basically forced the rest of Americans to subsidize a tax cut for the rich.

And one more point I would like to make. Interest on the national debt currently gobbles up 8 cents out of every tax dollar. The budget deficit for 2020 was $3.7 TRILLION (slightly less than the chart above projects — I included the chart for the trend line). Even before the pandemic hit, necessitating emergency spending, the Trump tax cuts had driven projected deficits way up over where they were by the end of the Obama Administration. Some will try to tell you that those tax cuts simply returned money to the pockets of Americans. Bull. Every dollar that Donald Trump added to the deficit increased that interest expenditure I just mentioned and forced the rest to pay more. By skewing his cuts to the wealthiest among us, he basically forced the rest of Americans to subsidize a tax cut for the rich. I was watching that night, along with pretty much every other eleven year-old, baseball-loving boy in America. I remember everything about it — the call from announcer Vin Scully, the twist and high stare of Dodgers pitcher Al Downing as he watched the ball sail out over left field, Aaron’s joyful trot around the bases, the two white guys in civilian clothes who appeared out of nowhere as he rounded second base and patted his back and shoulder, the way his jubilant teammates mobbed him at home plate and put him on their shoulders. I still have the issue of Sports Illustrated from the next week, with Aaron on the cover holding up the baseball next to a golden, bolded “715.” And I also still have the special edition baseball card Topps issued that same year proclaiming Aaron baseball’s home run king.

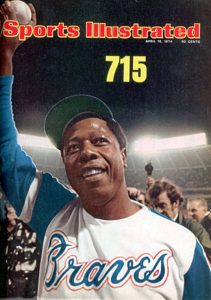

I was watching that night, along with pretty much every other eleven year-old, baseball-loving boy in America. I remember everything about it — the call from announcer Vin Scully, the twist and high stare of Dodgers pitcher Al Downing as he watched the ball sail out over left field, Aaron’s joyful trot around the bases, the two white guys in civilian clothes who appeared out of nowhere as he rounded second base and patted his back and shoulder, the way his jubilant teammates mobbed him at home plate and put him on their shoulders. I still have the issue of Sports Illustrated from the next week, with Aaron on the cover holding up the baseball next to a golden, bolded “715.” And I also still have the special edition baseball card Topps issued that same year proclaiming Aaron baseball’s home run king.